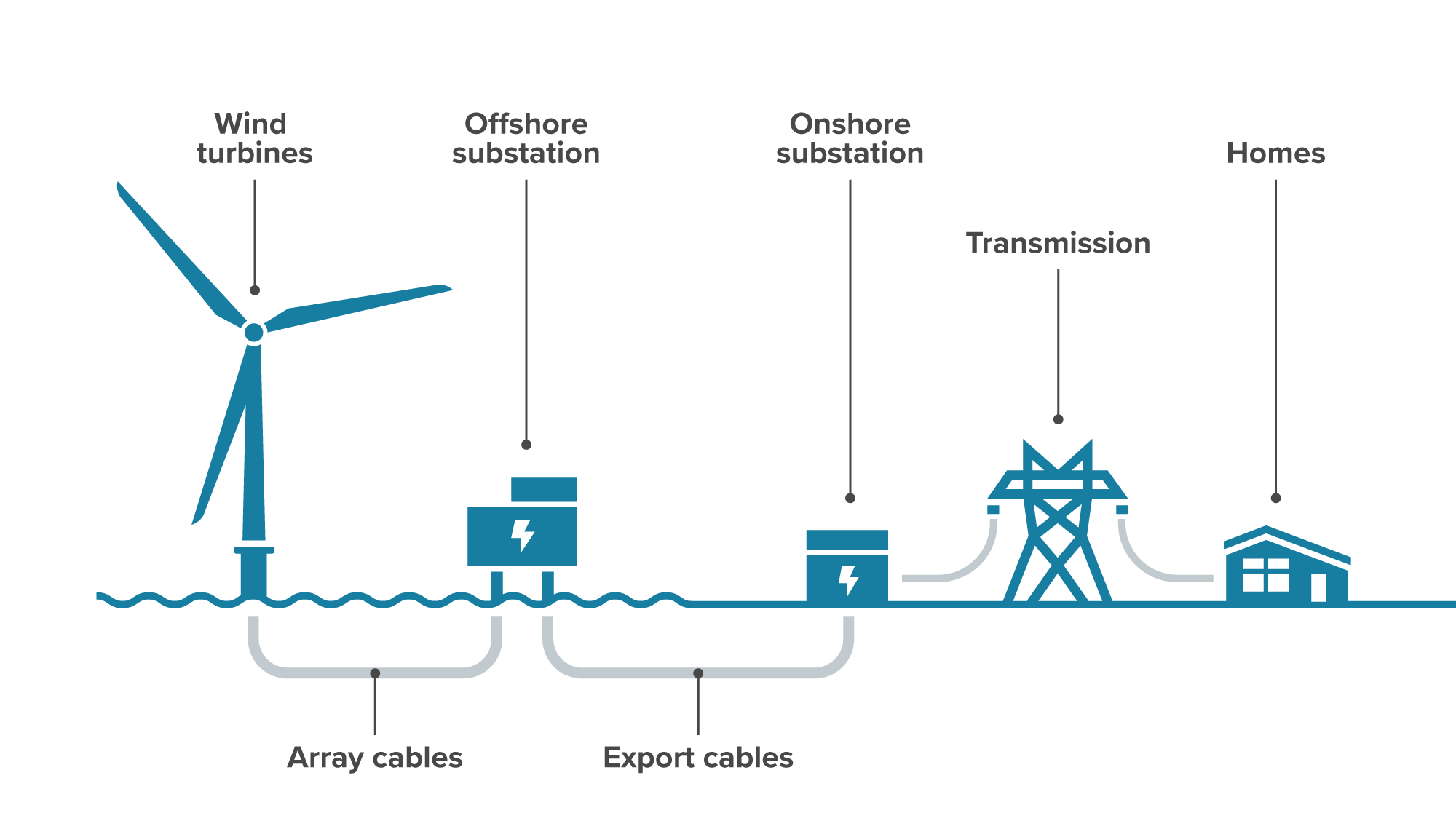

There are many stages involved in a composting system to convert organic MSW into finished compost that can be used to improve soil health (Figure 1). Within this system, composting is the biochemical process that transforms OW into a soil amendment rich in nutrients and organic matter.

Increase Centralized Composting

A composting system diverts organic waste (OW) from landfills, reducing the production of methane and other GHG emissions. OW is defined as the combination of food waste and green waste, composed of yard and garden trimmings. Composting transforms it into a nutrient-rich soil supplement.

Our focus is on centralized (city- or regional-level) composting systems for the OW components of municipal solid waste (MSW). Decentralized (home- and community-level) and on-farm composting are also valuable climate actions, but are not included here due to limited data availability at the global level (see Increase Decentralized Composting).

Figure 1. Stages of a composting system. Solution boundaries exclude activities upstream and downstream of centralized MSW composting such as waste collection and compost application. Modified from Kawai et al. (2020) and Manea et al. (2024).

Sources: Kawai, K., Liu, C., & Gamaralalage, P. J. D. (2020). CCET guideline series on intermediate municipal solid waste treatment technologies: Composting. United Nations Environment Programme; Manea, E. E., Bumbac, C., Dinu, L. R., Bumbac, M., & Nicolescu, C. M. (2024). Composting as a sustainable solution for organic solid waste management: Current practices and potential improvements. Sustainability, 16(15), Article 6329.

The composting process is based on aerobic decomposition, driven by complex interactions among microorganisms, biodegradable materials, and invertebrates and mediated by water and oxygen (see the Appendix). Without the proper balance of oxygen and water, anaerobic decomposition occurs, leading to higher methane emissions during the composting process (Amuah et al., 2022; Manea et al., 2024). Multiple composting methods can be used depending on the amounts and composition of OW feedstocks, land availability, labor availability, finances, policy landscapes, and geography. Some common methods include windrow composting, bay or bin systems, and aerated static piles (Figure 2; Amuah et al., 2022; Ayilara et al., 2020; Cao et al., 2023).

Figure 2. Examples of commonly used centralized composting methods. Bay systems (left) move organics between different bays at different stages of the composting process. Windrows (center) are long, narrow piles that are often turned using large machinery. Aerated static piles (right) can be passively aerated as shown here or actively aerated with specialized blowing equipment.

Credit: Bays, iStock | nikolay100; Windrows, iStock | Jeremy Christensen; Aerated static pile, iStock | AscentXmedia

Centralized composting generally refers to processing large quantities (>90 t/week) of organic MSW (Platt, 2017). Local governments often manage centralized composting as part of an integrated waste management system that can also include recycling non-OW, processing OW anaerobically in methane digesters, landfilling, and incineration (Kaza et al., 2018).

Organic components of MSW include food waste and garden and yard trimmings (Figure 2). In most countries and territories, these make up 40–70% of MSW, with food waste as the largest contribution (Ayilara et al., 2020; Cao et al., 2023; Food and Agriculture Organization [FAO], 2019; Kaza et al., 2018; Manea et al., 2024; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency [U.S. EPA], 2020; U.S. EPA, 2023).

Diverting OW, particularly food waste, from landfill disposal to composting reduces GHG emissions (Ayilara et al., 2020; Cao et al., 2023; FAO, 2019). Diversion of organics from incineration could also have emissions and pollution reduction benefits, but we did not include incineration as a baseline disposal method for comparison since it is predominantly used in high-capacity and higher resourced countries and contributes less than 1% to annual waste-sector emissions (Intergovernmental Panel On Climate Change [IPCC], 2023; Kaza et al., 2018).

Disposal of waste in landfills leads to methane emissions estimated at nearly 1.9 Gt CO₂‑eq (100-yr basis) annually (International Energy Agency [IEA], 2024). Landfill emissions come from anaerobic decomposition of inorganic waste and OW and are primarily methane with smaller contributions from ammonia, nitrous oxide, and CO₂ (Cao et al., 2023; Kawai et al., 2020; Manea et al., 2024). Although CO₂, methane, and nitrous oxide are released during composting, methane emissions are up to two orders of magnitude lower than emissions from landfilling for each metric ton of waste (Ayilara et al., 2020; Cao et al, 2023; FAO, 2019; IEA, 2024; Nordahl et al., 2023; Perez et al., 2023). GHG emissions can be minimized by fine-tuning the nutrient balance during composting.

Depending on the specifics of the composting method used, the full transformation from initial feedstocks to finished compost can take weeks or months (Amuah et al., 2022; Manea et al., 2024; Perez et al., 2023). Finished compost can be sold and used in a variety of ways, including application to agricultural lands and green spaces as well as for soil remediation (Gilbert et al., 2020; Platt et al., 2022; Ricci-Jürgensen et al., 2020a; Sánchez et al., 2025).

Abedin, T., Pasupuleti, J., Paw, J.K.S., Tak, Y. C., Islam, M. R., Basher, M. K., & Nur-E-Alam, M. (2025). From waste to worth: Advances in energy recovery technologies for solid waste management. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy, 27, 5963–5989. Link to source: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-025-03204-x

Alves Comesaña, D., Villar Comesaña, I., & Mato de la Iglesia, S. (2024). Community composting strategies for biowaste treatment: Methodology, bulking agent and compost quality. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 31(7), 9873–9885. Link to source: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-25564-x

Amuah, E. E. Y., Fei-Baffoe, B., Sackey, L. N. A., Douti, N. B., & Kazapoe, R. W. (2022). A review of the principles of composting: Understanding the processes, methods, merits, and demerits. Organic Agriculture, 12(4), 547–562. Link to source: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13165-022-00408-z

Ayilara, M., Olanrewaju, O., Babalola, O., & Odeyemi, O. (2020). Waste management through composting: Challenges and potentials. Sustainability, 12(11), Article 4456. Link to source: https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114456

Bekchanov, M., & Mirzabaev, A. (2018). Circular economy of composting in Sri Lanka: Opportunities and challenges for reducing waste related pollution and improving soil health. Journal of Cleaner Production, 202, 1107–1119. Link to source: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.08.186

Bell, B., & Platt, B. (2014). Building healthy soils with compost to protect watersheds. Institute for Local Self-Reliance. Link to source: https://ilsr.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Compost-Builds-Healthy-Soils-ILSR-5-08-13-2.pdf

Brown, S. (2015, July 14). Connections: YIMBY. Biocycle. Link to source: https://www.biocycle.net/connections-yimby/

Cai, B., Lou, Z., Wang, J., Geng, Y., Sarkis, J., Liu, J., & Gao, Q. (2018). CH4 mitigation potentials from China landfills and related environmental co-benefits. Science Advances, 4(7), Article eaar8400. Link to source: https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aar8400

Cao, X., Williams, P. N., Zhan, Y., Coughlin, S. A., McGrath, J. W., Chin, J. P., & Xu, Y. (2023). Municipal solid waste compost: Global trends and biogeochemical cycling. Soil & Environmental Health, 1(4), Article 100038. Link to source: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seh.2023.100038

Casey, J. A., Cushing, L., Depsky, N., & Morello-Frosch, R. (2021). Climate justice and California’s methane superemitters: Environmental equity Assessment of community proximity and exposure intensity. Environmental Science & Technology, 55(21), 14746–14757. Link to source: https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.1c04328

Coker, C. (2020, March 3). Composting business management: Revenue forecasts for composters. Biocycle. Link to source: https://www.biocycle.net/composting-business-management-revenue-forecasts-composters/

Coker, C. (2020, March 10). Composting business management: Capital cost of composting facility construction. Biocycle. Link to source: https://www.biocycle.net/composting-business-management-capital-cost-composting-facility-construction/

Coker, C. (2020, March 17). Composting business management: Composting facility operating cost estimates. Biocycle. Link to source: https://www.biocycle.net/composting-business-management-composting-facility-operating-cost-estimates/

Coker, C. (2022, August 23). Compost facility planning: Composting facility approvals and permits. Biocycle. Link to source: https://www.biocycle.net/composting-facility-approval-permits/

Coker, C. (2022, September 27). Compost facility planning: Composting facility cost estimates. Biocycle. Link to source: https://www.biocycle.net/compost-facility-planning-cost/

Coker, C. (2024, August 20). Compost market development. Biocycle. Link to source: https://www.biocycle.net/compost-market-development/

European Energy Agency. (2024). Greenhouse gas emissions by source sector. (Last Updated: April 18, 2024). Eurostat. [Data set and codebook]. Link to source: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/env_air_gge__custom_16006716/default/table

Farhidi, F., Madani, K., & Crichton, R. (2022). How the US economy and environment can both benefit from composting management. Environmental Health Insights, 16. Link to source: https://doi.org/10.1177/11786302221128454

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2024). The state of food and agriculture 2024 – Value-driven transformation of agrifood systems. Link to source: https://doi.org/10.4060/cd2616en

Finlay, K. (2024). Turning down the heat: how the U.S. EPA can fight climate change by cutting landfill emissions. Industrious Labs. Link to source: https://cdn.sanity.io/files/xdjws328/production/657706be7f29a20fe54692a03dbedce8809721e8.pdf

Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives. (2019). Pollution and health impacts of waste-to-energy incineration [Fact sheet]. Link to source: https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/delivering-service-school-based-settings-comprehensive-guide-medicaid-services-and-administrative

González, D., Barrena, R., Moral-Vico, J., Irigoyen, I., & Sánchez, A. (2024). Addressing the gaseous and odour emissions gap in decentralised biowaste community composting. Waste Management, 178, 231–238. Link to source: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2024.02.042

International Energy Agency. (2024), Global Methane Tracker 2024. Link to source: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-methane-tracker-2024

Intergovernmental Panel On Climate Change. (2023). Climate change 2022 – Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability: Working Group II contribution to the sixth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. Link to source: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009325844

Intergovernmental Panel On Climate Change. (2019). 2019 Refinement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories, Calvo. Buendia, E., Tanabe, K., Kranjc, A., Baasansuren, J., Fukuda, M., Ngarize S., Osako, A., Pyrozhenko, Y., Shermanau, P. and Federici, S. (eds). Link to source: https://www.ipcc-nggip.iges.or.jp/public/2019rf/index.html

Jamroz, E., Bekier, J., Medynska-Juraszek, A., Kaluza-Haladyn, A., Cwielag-Piasecka, I., & Bednik, M. (2020). The contribution of water extractable forms of plant nutrients to evaluate MSW compost maturity: A case study. Scientific Reports, 10(1), Article 12842. Link to source: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-69860-9

Kawai, K., Liu, C., & Gamaralalage, P. J. D. (2020). CCET guideline series on intermediate municipal solid waste treatment technologies: Composting. United Nations Environment Programme. Link to source: https://www.unep.org/ietc/resources/publication/ccet-guideline-series-intermediate-municipal-solid-waste-treatment

Kaza, S., Yao, L. C., Bhada-Tata, P., Van Woerden, F., (2018). What a waste 2.0: A global snapshot of solid waste management to 2050. Urban Development. World Bank. Link to source: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/30317

Krause, M., Kenny, S., Stephenson, J., & Singleton, A. (2023). Quantifying methane emissions from landfilled food waste (Report No. EPA-600-R-23-064). U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Research and Development. Link to source: https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2023-10/food-waste-landfill-methane-10-8-23-final_508-compliant.pdf

Liu, K-. M., Lin, S-. H., Hsieh, J-., C., Tzeng, G-., H. (2018). Improving the food waste composting facilities site selection for sustainable development using a hybrid modified MADM model. Waste Management, 75, 44–59. Link to source: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2018.02.017

Liu, H., Zhang, X., & Hong, Q. (2021). Emission characteristics of pollution gases from the combustion of food waste. Energies, 14(19), Article 6439. Link to source: https://doi.org/10.3390/en14196439

Maalouf, A., & Agamuthu, P. (2023). Waste management evolution in the last five decades in developing countries – A review. Waste Management & Research: The Journal for a Sustainable Circular Economy, 41(9), 1420–1434. Link to source: https://doi.org/10.1177/0734242X231160099

Manea, E. E., Bumbac, C., Dinu, L. R., Bumbac, M., & Nicolescu, C. M. (2024). Composting as a sustainable solution for organic solid waste management: Current practices and potential improvements. Sustainability, 16(15), Article 6329. Link to source: https://doi.org/10.3390/su16156329

Martínez-Blanco, J., Lazcano, C., Christensen, T. H., Muñoz, P., Rieradevall, J., Møller, J., Antón, A., & Boldrin, A. (2013). Compost benefits for agriculture evaluated by life cycle assessment. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development, 33(4), 721–732. Link to source: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-013-0148-7

Martuzzi, M., Mitis, F., & Forastiere, F. (2010). Inequalities, inequities, environmental justice in waste management and health. The European Journal of Public Health, 20(1), 21–26. Link to source: https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckp216

Nordahl, S. L., Devkota, J. P., Amirebrahimi, J., Smith, S. J., Breunig, H. M., Preble, C. V., Satchwell, A. J., Jin, L., Brown, N. J., Kirchstetter, T. W., & Scown, C. D. (2020). Life-Cycle greenhouse gas emissions and human health trade-offs of organic waste management strategies. Environmental Science & Technology, 54(15), 9200–9209. Link to source: https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.0c00364

Nordahl, S. L., Preble, C. V., Kirchstetter, T. W., & Scown, C. D. (2023). Greenhouse gas and air pollutant emissions from composting. Environmental Science & Technology, 57(6), 2235–2247. Link to source: https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.2c05846

Nubi, O., Murphy, R., & Morse, S. (2024). Life cycle sustainability assessment of waste to energy systems in the developing world: A review. Environments, 11(6), 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments11060123

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2021). Waste - Municipal waste: generation and treatment. (Downloaded: March 20, 2025) [Data set]. Link to source: https://data-explorer.oecd.org/vis?lc=en&df[ds]=dsDisseminateFinalDMZ&df[id]=DSD_MUNW%40DF_MUNW&df[ag]=OECD.ENV.EPI&dq=.A.INCINERATION_WITHOUT%2BLANDFILL.T&pd=2014%2C&to[TIME_PERIOD]=false&vw=ov

Pérez, T., Vergara, S. E., & Silver, W. L. (2023). Assessing the climate change mitigation potential from food waste composting. Scientific Reports, 13(1), Article 7608. Link to source: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-34174-z

Platt, B., Bell, B., & Harsh, C. (2013). Pay dirt: Composting in Maryland to reduce waste, create jobs, & protect the bay. Institute for Local Self-Reliance. Link to source: https://ilsr.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Pay-Dirt-Report.pdf

Platt, B. (2017, April 4). Hierarchy to Reduce Food Waste & Grow Community, Institute for Local Self-Reliance. Link to source: https://ilsr.org/articles/food-waste-hierarchy/

Platt, B., and Fagundes, C. (2018). Yes! In my backyard: A home composting guide for local government. Institute for Local Self-Reliance. Link to source: https://ilsr.org/articles/yimby-compost/

Platt, B., Libertelli, C., & Matthews, M. (2022). A growing movement: 2022 community composter census. Institute for Local Self-Reliance. Link to source: https://ilsr.org/articles/composting-2022-census/

Ricci-Jürgensen, M., Gilbert, J., & Ramola, A.. (2020a). Global assessment of municipal organic waste production and recycling. International Solid Waste Association. Link to source: https://www.altereko.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Report-1-Global-Assessment-of-Municipal-Organic-Waste.pdf

Ricci-Jürgensen, M., Gilbert, J., & Ramola, A.. (2020b). Benefits of compost and anaerobic digestate when applied to soil. International Solid Waste Association. Link to source: https://www.altereko.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Report-2-Benefits-of-Compost-and-Anaerobic-Digestate.pdf

Rynk, R., Black, G., Biala, J., Bonhotal, J., Cooperband, L., Gilbert, J., & Schwarz, M. (Eds.). (2021). The composting handbook. Compost Research & Education Foundation and Elsevier. Link to source: https://www.compostingcouncil.org/store/viewproduct.aspx?id=19341051

Sánchez, A., Gea, T., Font, X., Artola, A., Barrena, R., & Moral-Vico, J. (Eds.). (2025). Composting: Fundamentals and Recent Advances: Chapter 1. Royal Society of Chemistry. Link to source: https://doi.org/10.1039/9781837673650

Souza, M. A. d., Gonçalves, J. T., & Valle, W. A. d. (2023). In my backyard? Discussing the NIMBY effect, social acceptability, and residents’ involvement in community-based solid waste management. Sustainability, 15(9), Article 7106. Link to source: https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097106

The Environmental Research & Education Foundation. (2024). Analysis of MSW landfill tipping fees — 2023. Link to source: https://erefdn.org/product/analysis-of-msw-landfill-tipping-fees-2023/

U.S. Composting Council. (2008). Greenhouse gases and the role of composting: A primer for compost producers [Fact sheet]. Link to source: https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.compostingcouncil.org/resource/resmgr/documents/GHG-and-Role-of-Composting-a.pdf

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2020). 2018 wasted food report (EPA Publication No. EPA 530-R-20-004). Office of Resource Conservation and Recovery. Link to source: https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2025-02/2018_wasted_food_report-v2.pdf

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2023). 2019 Wasted food report (EPA Publication No. 530-R-23-005). National Institutes of Health. Link to source: https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2024-04/2019-wasted-food-report_508_opt_ec_4.23correction.pdf

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2023). Documentation for Greenhouse Gas Emission and Energy Factors Used in the Waste Reduction Model (WARM): Organic Materials Chapters (EPA Publication No. EPA-530-R-23-019). Office of Resource Conservation and Recovery. Link to source: https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2023-12/warm_organic_materials_v16_dec.pdf

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2025, January). Approaches to composting. Link to source: https://www.epa.gov/sustainable-management-food/approaches-composting

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2025, April). Benefits of using compost. Link to source: https://www.epa.gov/sustainable-management-food/benefits-using-compost

United Nations Environment Programme. (2023). Towards Zero Waste: A Catalyst for delivering the Sustainable Development Goals. Link to source: https://doi.org/10.59117/20.500.11822/44102

United Nations Environment Programme. (2024). Global Waste Management Outlook 2024 Beyond an age of waste: Turning rubbish into a resource. Link to source: https://www.unep.org/resources/global-waste-management-outlook-2024

Urra, J., Alkorta, I., & Garbisu, C. (2019). Potential benefits and risks for soil health derived from the use of organic amendments in agriculture. Agronomy, 9(9), 542. Link to source: https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy9090542

Wilson, D. C., Paul, J., Ramola, A., & Filho, C. S. (2024). Unlocking the significant worldwide potential of better waste and resource management for climate mitigation: With particular focus on the Global South. Waste Management & Research: The Journal for a Sustainable Circular Economy, 42(10), 860–872. Link to source: https://doi.org/10.1177/0734242X241262717

World Bank. (2018). What a waste global database: Country-level dataset. (Last Updated: June 4, 2024) [Data set]. World Bank. Link to source: https://datacatalogfiles.worldbank.org/ddh-published/0039597/3/DR0049199/country_level_data.csv

Yasmin, N., Jamuda, M., Panda, A. K., Samal, K., & Nayak, J. K. (2022). Emission of greenhouse gases (GHGs) during composting and vermicomposting: Measurement, mitigation, and perspectives. Energy Nexus, 7, Article 100092. Link to source: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nexus.2022.100092

Zaman, A. U. (2016). A comprehensive study of the environmental and economic benefits of resource recovery from global waste management systems. Journal of Cleaner Production, 124, 41–50. Link to source: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.02.086

Zero Waste Europe & Bio-based Industries Consortium. (2024). Bio-waste generation in the EU: Current capture levels and future potential (Second edition). LIFE Programme of the European Union. Link to source: https://zerowasteeurope.eu/library/bio-waste-generation-in-the-eu-current-capture-levels-and-future-potential-second-edition/

Zhu, J., Luo, Z., Sun, T., Li, W., Zhou, W., Wang, X., Fei, X., Tong, H., & Yin, K. (2023). Cradle-to-grave emissions from food loss and waste represent half of total greenhouse gas emissions from food systems. Nature Food, 4(3), 247–256. Link to source: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-023-00710-3

Lead Fellow

Megan Matthews, Ph. D.

Contributors

Ruthie Burrows, Ph.D.

James Gerber, Ph.D.

Daniel Jasper

Alex Sweeney

Internal Reviewers

Aiyana Bodi

Hannah Henkin

Ted Otte

Sarah Gleeson, Ph. D.

Amanda D. Smith, Ph.D.

Paul C. West, Ph.D.

We estimated that composting reduces emissions by 3.9 t CO₂‑eq /t OW (9.3 t CO₂‑eq /t OW, 20-yr basis) based on avoided landfill emissions minus the emissions during composting of MSW OW (Table 1). In our analysis, composting emissions were an order of magnitude lower than landfill emissions.

Table 1. Effectiveness at reducing emissions.

Unit: t CO₂‑eq (100-yr basis)/t OW

| 25th percentile | 2.5 |

| Mean | 3.2 |

| Median (50th percentile) | 3.9 |

| 75th percentile | 4.3 |

Emissions data from composting and landfilling OW are geographically limited, but our analysis includes three global reports and studies from the U.S., China, Denmark, and the EU (European Energy Agency [EEA], 2024; Industrious Labs, 2024; Perez et al., 2023; U.S. EPA, 2020; Yang et al., 2017, Yasmin et al., 2022). We assumed OW was 39.6% of MSW in accordance with global averages (Kaza et al., 2018; World Bank, 2018).

We estimated that landfills emit 4.3 t CO₂‑eq /t OW (9.9 t CO₂‑eq /t OW, 20-yr basis). We estimated composting emissions were 10x lower at 0.4 t CO₂‑eq /t OW (0.6 t CO₂‑eq /t OW, 20-yr basis). We quantified emissions from a variety of composting methods and feedstock mixes (Cao et al., 2023; Perez et al., 2023; Yasmin et al., 2022). Consistent with Amuah et al. (2022), we assumed a 60% moisture content by weight to convert reported wet waste quantities to dry waste weights. We based effectiveness estimates only on dry OW weights. For adoption and cost, we did not distinguish between wet and dry OW.

Financial data were geographically limited. We based cost estimates on global reports with selected studies from the U.K., U.S., India, and Saudi Arabia for landfilling and the U.S. and Sri Lanka for composting. Transportation and collection costs can be significant in waste management, but we did not include them in this analysis. We calculated amortized net cost for landfilling and composting by subtracting revenues from operating costs and amortized initial costs over a 30-yr facility lifetime.

Landfill initial costs are one-time investments, while operating expenses, which include maintenance, wages, and labor, vary annually. Environmental costs, including post-closure operations, are not included in our analysis, but some countries impose taxes on landfilling to incentivize alternative disposal methods and offset remediation costs. Landfills generate revenue through tip fees and sales of landfill gas (Environmental Research & Education Foundation [EREF], 2023; Kaza et al., 2018). We estimated that landfilling is profitable, with a net cost of –US$30/t OW.

Initial and operational costs for centralized composting vary depending on method and scale (IPCC, 2023; Manea et al., 2024), but up-front costs are generally cheaper than landfilling. Since composting is labor-intensive and requires monitoring, operating costs can be higher, particularly in regions that do not impose landfilling fees (Manea et al., 2024).

Composting facilities generate revenue through tip fees and sales of compost products. Compost sales alone may not be sufficient to recoup costs, but medium- to large-scale composting facilities are economically viable options for municipalities (Kawai et al., 2020; Manea et al., 2024). We estimated the net composting cost to be US$20/t OW. The positive value indicates that composting is not globally profitable; however, decentralized systems that locally process smaller waste quantities can be profitable using low-cost but highly efficient equipment and methods (see Increase Decentralized Composting).

We estimated that composting costs US$50/t OW more than landfilling. Although composting systems cost more to implement, the societal and environmental costs are greatly reduced compared to landfilling (Yasmin et al., 2022). The high implementation cost is a barrier to adoption in lower-resourced and developing countries (Wilson et al., 2024).

Combining effectiveness with the net costs presented here, we estimated a cost per unit climate impact of US$10/t CO₂‑eq (US$5/t CO₂‑eq , 20-yr basis) (Table 2).

Table 2. Cost per unit climate impact.

Unit: US$ (2023)/t CO₂‑eq (100-yr basis)

| Median | 10 |

Global cost data on composting are limited, and costs can vary depending on composting methods, so we did not quantify a learning rate for centralized composting.

Speed of action refers to how quickly a climate solution physically affects the atmosphere after it is deployed. This is different from speed of deployment, which is the pace at which solutions are adopted.

At Project Drawdown, we define the speed of action for each climate solution as emergency brake, gradual, or delayed.

Increase Centralized Composting is an EMERGENCY BRAKE climate solution. It has the potential to deliver a more rapid impact than nominal and delayed solutions. Because emergency brake solutions can deliver their climate benefits quickly, they can help accelerate our efforts to address dangerous levels of climate change. For this reason, they are a high priority.

The composting process has a low risk of reversal since carbon is stored stably in finished compost instead of decaying and releasing methane in a landfill (Ayilara et al., 2020; Manea et al., 2024). However, a composting system, from collection to finished product, can be challenging to sustain. Along with nitrogen-rich food and green waste, additional carbon-rich biomass, called bulking material, is critical for maintaining optimal composting conditions that minimize GHG emissions. Guaranteeing the availability of sufficient bulking materials can challenge the success of both centralized and decentralized facilities.

Financially and environmentally sustainable composting depends not only on the quality of incoming OW feedstocks, but also on the quality of the final product. Composting businesses require a market for sales of compost products (in green spaces and/or agriculture), and poor source separation could lead to low-quality compost and reduced demand (Kawai et al., 2020; Wilson et al., 2024). Improvements in data collection and quality through good feedback mechanisms can also act as leverage for expanding compost markets, pilot programs, and growing community support.

If composting facilities close due to financial or other barriers, local governments may revert to disposing of organics in landfills. Zoning restrictions also vary broadly across geographies, affecting how easily composting can be implemented (Cao et al., 2023). In regions where centralized composting is just starting, reversal could be more likely without community engagement and local government support (Kawai et al., 2020; Maalouf & Agamuthu, 2023); however, even if facilities close, the emissions savings from past operation cannot be reversed.

We estimated global composting adoption at 78 million t OW/yr, as the median between two datasets (Table 3). The most recent global data on composting were compiled in 2018 from an analysis from 174 countries and territories (World Bank, 2018). We also used an Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) analysis from 45 countries (OECD, 2021). However, there were still many countries and territories that did not report composting data in one or both datasets. Although the World Bank dataset is comprehensive, it is based on data collected in 2011–2018, so more recent, high-quality, global data on composting are needed.

Table 3. Current adoption level (2021).

Unit: t OW composted/yr

| 25th percentile | 67,000,000 |

| Mean | 78,000,000 |

| Median (50th percentile) | 78,000,000 |

| 75th percentile | 89,000,000 |

Globally in 2018, nearly 40% of all waste was disposed of in landfills, 19% was recovered through composting and other recovery and recycling methods, and the remaining waste was either unaccounted for or disposed of through open dumping and wastewater (Kaza et al., 2018)

We calculated total tonnage composted using the reported composting percentages and the total MSW tonnage for each country. Composting percentages were consistently lower than the total percentage of OW present in MSW, suggesting there is ample opportunity for increased composting, even in geographies where it is an established disposal method. In 2018, 26 countries/territories had a composting rate above 10% of MSW, and 15 countries/territories had a composting rate above 20% of MSW. Countries with the highest composting rates were Austria (31%), the Netherlands (27%), and Switzerland (21%) (World Bank, 2018).

We used OECD data to estimate the composting adoption trend from 2014–2021 (OECD, 2021), which fluctuated significantly from year to year (Table 4). Negative rates indicate less OW was composted globally than in the previous year. Taking the median composting rate across seven years, we estimate the global composting trend as 260,000 t OW/yr/yr. However, the mean composting trend is –1.3 Mt OW/yr/yr, suggesting that on average, composting rates are decreasing globally.

Table 4. Adoption trend (2014–2021).

Unit: t OW composted/yr/yr

| 25th percentile | -1,200,000 |

| Mean | -1,300,000 |

| Median (50th percentile) | 260,000 |

| 75th percentile | 4,300,000 |

Although some regions are increasing their composting capacity, others are either not composting or composting less over time. Germany, Italy, Spain, and the EU overall consistently show increases in composting rates year-to-year, while Greece, Japan, Türkiye, and the U.K. show decreasing composting rates. In Europe, the main drivers for consistent adoption were disposal costs, financial penalties, and the landfill directive (Ayilara et al., 2020).

Lack of reported data could also contribute to a negative global average composting rate over the past seven years. A large decline in composting rates from 2018–2019 was driven by a lack of data in 2019 for the U.S. and Canada. If we assumed that the U.S. composted the same tonnage in 2019 as in 2018, instead of no tonnage as reported in the data, then the annual trend for 2018–2019 is much less negative (–450,000 t OW/yr/yr) and the overall mean trend between 2014–2019 would be positive (1,400,000 t OW/yr/yr).

We estimate the global adoption ceiling for Increase Centralized Composting to be 1.35 billion t OW/yr (Table 5). In 2016, 2.01 Gt of MSW were generated, and generation is expected to increase to 3.4 Gt by 2050 (Kaza et al., 2018). Due to limited global data availability on composting infrastructure or policies, we estimated the adoption ceiling based on the projected total MSW for 2050 and assumed the OW fraction remains the same over time.

Table 5. Adoption ceiling. upper limit for adoption level.

Unit: t OW composted/yr

| Median (50th percentile) | 1,350,000,000 |

In reality, amounts of food waste within MSW are also increasing, suggesting that there are sufficient global feedstocks to support widespread composting adoption (Zhu et al., 2023).

We assume that all OW could be processed via composting, but this ceiling is unlikely to be reached. In practice, organics could also be processed via methane digesters (see Deploy Methane Digesters), incinerated, or dumped, but these waste management treatments have similar environmental risks to landfilling.

Since the global annual trend fluctuates, we used country-specific composting rates and organic fractions of MSW from 2018 to estimate the achievable range of composting adoption (see Appendix for an example). In our analysis, achievable increases in country-specific composting rates cannot exceed the total organic fraction of 2018 MSW.

For the 106 countries/territories that did not report composting rates, we defined achievable levels of composting relative to the fraction of OW in MSW. When countries also did not report OW percentages, the country-specific composting rate was kept at zero. For the remaining 86 countries/territories, we assumed that 25% of organic MSW could be diverted to composting for low achievable adoption and that 50% could be diverted for high achievable adoption.

For the 68 countries/territories with reported composting rates, we define low and high achievable adoption as a 25% or 50% increase to the country-specific composting rate, respectively. If the increased rate for either low or high adoption exceeded the country-specific OW fraction of MSW, we assumed that all organic MSW could be composted (see Appendix for an example). Our Achievable – Low adoption level is 201 Mt OW/yr, or 15% of our estimated adoption ceiling (Table 6). Our Achievable – High adoption level is 301 Mt OW/yr, or 22% of our estimated adoption ceiling.

Table 6. Range of achievable adoption levels.

Unit: t OW composted/yr

| Current adoption | 78,000,000 |

| Achievable – low | 201,000,000 |

| Achievable – high | 301,000,000 |

| Adoption ceiling | 1,350,000,000 |

Our estimated adoption levels are conservative because some regions without centralized composting of MSW could have subnational decentralized composting programs that aren’t reflected in global data.

Although our achievable range is conservative compared to the estimated adoption ceiling, increased composting has the potential to reduce GHG emissions from landfills (Table 7). We estimated that current adoption reduces annual GHG emissions by 0.3 Gt CO₂‑eq/yr (0.73 Gt CO₂‑eq/yr, 20-yr basis). Our estimated low and high achievable adoption levels reduce 0.78 and 1.2 Gt CO₂‑eq/yr (1.9 and 2.8 Gt CO₂‑eq/yr, 20-yr basis), respectively. Using the adoption ceiling, we estimate that annual GHG reductions increase to 5.2 Gt CO₂‑eq/yr (12.6 Gt CO₂‑eq/yr, 20-yr basis).

Table 7. Climate impact at different levels of adoption.

Unit: Gt CO₂‑eq (100-yr basis)/yr

| Current adoption | 0.30 |

| Achievable – low | 0.78 |

| Achievable – high | 1.2 |

| Adoption ceiling | 5.2 |

The IPCC estimated in 2023 that the entire waste sector accounted for 3.9% of total global GHG emissions, and solid waste management represented 36% of total waste sector emissions (IPCC, 2023). Disposal of waste in landfills leads to methane emissions estimated at nearly 1.9 Gt CO₂‑eq (100-yr basis) annually (IEA, 2024). Based on these estimates, current composting adoption reduces annual methane emissions from landfills more than 16%.

Increasing adoption to low and high achievable levels could reduce the amount of OW going to landfills by up to 40% and avoid 32–50% of landfill emissions. Reaching our estimated adoption ceilings for Increase Centralized Composting and reduction-focused solutions like Reduce Food Loss and Waste could avoid all food-related landfill emissions.

These climate impacts can be considered underestimates of beneficial mitigation from increased composting since we did not quantify the carbon sequestration benefits of compost application and reduced synthetic fertilizer use. Our estimated climate impacts from composting are also an underestimate because we didn’t include decentralized composting.

Income and Work

Composting creates more jobs than landfills or incinerators and can save money compared with other waste management options (Bekchanov & Mirzabaev, 2018; Farhidi et al., 2022; Platt et al., 2013; Zaman, 2016). It is less expensive to build and maintain composting plants than incinerators (Kawai et al., 2020). According to a survey of Maryland waste sites, composting creates twice as many jobs as landfills and four times as many jobs as incineration plants (Platt et al., 2013). Composting also indirectly sustains jobs in the distribution and use of compost products (Platt et al., 2013). Compost is rich in nutrients and can also reduce costs associated with synthetic fertilizer use in agriculture (Farhidi et al., 2022).

Health

Odors coming from anaerobic decomposition landfills, such as ammonia and hydrogen sulfide, are another source of pollutants that impact human well-being, which can be reduced by aerobic composting (Cai et al., 2018).

Equality

Reducing community exposure to air pollution from landfills through composting has implications for environmental justice (Casey et al., 2021; Nguyen et al., 2023). A large review of waste sites in the United States and Europe found that landfills are disproportionately located near populations with low socioeconomic status and near racially and ethnically marginalized neighborhoods (Marzutti et al., 2010). Reducing disproportionate exposures to air pollution from landfills may mitigate poor health outcomes in surrounding communities (Brender et al., 2011)

Land Resources

Compost provides an important soil amendment that adds organic matter and nutrients to soil, reducing the need for synthetic fertilizers (Urra et al., 2019; U.S. EPA, 2025). Healthy soils that are rich in organic matter can benefit the surrounding ecosystem and watershed and lead to more plant growth through improved water retention and filtration, improved soil quality and structure, and reduced erosion and nutrient runoff (Bell & Platt, 2014; Martinez-Blanco et al., 2013; U.S. EPA, 2025). By reducing the need for synthetic fertilizers and by improving soils’ ability to filter and conserve water, compost can also reduce eutrophication of water bodies (U.S. EPA, 2025). These soil benefits are partially dependent on how compost is sorted because there may be risks associated with contamination of microplastics and heavy metals (Manea et al., 2024; Urra et al., 2019).

Water Resources

For a description of water resources benefits, please see Land Resources above.

Air Quality

Composting can reduce air pollution such as CO₂, methane, volatile organic compounds, and particulate matter that is commonly released from landfills and waste-to-energy systems (Kawai et al., 2020; Nordahl et al., 2020; Siddiqua et al., 2022). An analysis comparing emissions from MSW systems found composting to have lower emissions than landfilling and other waste-to-energy streams (Nordahl et al., 2020). Composting can also reduce the incidence of landfill fires, which release black carbon and carbon monoxide, posing risks to the health and safety of people in nearby communities (Nguyen et al., 2023).

Before the composting process can start, feedstocks are sorted to remove potential contaminants, including nonbiodegradable materials such as metal and glass as well as plastics, bioplastics, and paper products (Kawai et al., 2020; Perez et al., 2023; Wilson et al., 2024). While most contaminants can be removed through a variety of manual and mechanical sorting techniques, heavy metals and microplastics can become potential safety hazards or reduce finished compost quality (Manea et al., 2024). Paper and cardboard should be separated from food and green waste streams because they often contain contaminants such as glue or ink, and they degrade more slowly than other OW, leading to longer processing time and lower-quality finished compost (Kawai et al., 2020; Krause et al., 2023).

Successful and safe composting requires careful monitoring of compost piles to avoid anaerobic conditions and ensure sufficient temperatures to kill pathogens and weed seeds (Amuah et al., 2022; Ayilara et al., 2020; Cao et al., 2023; Kawai et al., 2020; Manea et al., 2024). Anaerobic conditions within the compost pile increase GHGs emitted during composting. Poorly managed composting facilities can also pose safety risks for workers and release odors, leading to community backlash (Cao et al., 2023; Manea et al., 2024; UNEP, 2024). Regional standards, certifications, and composter training programs are necessary to protect workers from hazardous conditions and to guarantee a safe and effective compost product (Kawai et al., 2020). Community outreach and education on the benefits of separating waste and composting prevent “not-in-my-backyard” attitudes or “NIMBYism” (Brown, 2015; Platt & Fagundes 2018) that may lead to siting composting facilities further from the communities they serve (Souza, et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2018).

Reinforcing

Increased composting could positively impact annual cropping by providing consistent, high-quality finished compost that can reduce dependence on synthetic fertilizers and improve soil health and crop yields.

High-quality sorting systems also allow for synergies that benefit all waste streams and create flexible, resilient waste management systems. Improving waste separation programs for composting can have spillover effects that also improve other waste streams, such as recyclables, agricultural waste, or e-waste. Access to well-sorted materials can also help with nutrient balance for various waste streams, including agricultural waste.

Composting facilities require a reliable source of carbon-rich bulking material. Agricultural waste can be diverted to composting rather than burning to reduce emissions from crop residue burning.

Competing

Diverting OW from landfills will lead to lower landfill methane emissions and, therefore, less methane available to be captured and resold as revenue.

Composting uses wood, crop residues, and food waste as feedstocks (raw material). Because the total projected demand for biomass feedstocks for climate solutions exceeds the supply, not all solutions will be able to achieve their potential adoption. This solution is in competition with other climate solutions for raw material.

Solution Basics

t organic waste

Climate Impact

CO₂, CH₄

Robust collection networks and source separation of OW are vital for successful composting, but they also increase investment costs. However, well-sorted OW can reduce the need for separation equipment and allow for simpler facility designs, leading to lower operational costs. The emissions from transporting OW are not included here, but are expected to be significantly less than the avoided landfill emissions. Composting facilities are typically located close to the source of OW (Kawai et al., 2020; U.S. Composting Council [USCC], 2008), but since centralized composting facilities are designed to serve large communities and municipalities, there can be trade-offs between sufficient land availability and distance from waste sources.

We also exclude emissions from onsite vehicles and equipment such as bulldozers and compactors, assuming that those emissions are small compared to the landfill itself.

Per capita MSW generation, 2018

Annual generation of MSW per capita. Total global MSW generation exceeded 2 Gt/yr.

World Bank Group (2021). What a waste global database (Version 3) [Data set]. WBG. Retrieved March 6, 2025, from Link to source: https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/search/dataset/0039597

Per capita MSW generation, 2018

Annual generation of MSW per capita. Total global MSW generation exceeded 2 Gt/yr.

World Bank Group (2021). What a waste global database (Version 3) [Data set]. WBG. Retrieved March 6, 2025, from Link to source: https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/search/dataset/0039597

Globally, 17 countries reported composting more than 1 Mt each of organic waste in 2018, with India, China, Germany, and France reporting more than 5 Mt each (World Bank, 2018). With the exception of Austria, which composted nearly all organic waste generated, even countries with established centralized composting could divert more organic waste to composting.

The fate from which composting diverts organic waste varies from region to region, but globally over 40% of all waste ends up in landfills. Since organic waste makes up the largest percentage of MSW in most regions, excluding North America, parts of East Asia and the Pacific, and parts of Europe and Central Asia, there is ample opportunity to increase composting. In East Asia and the Pacific, South Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa, diverting organics to composting also avoids disposal in waterways and open dumps, which reduces pollution. In North America and Europe and Central Asia, 15–20% of MSW is incinerated (Kaza et al., 2018), so diverting all organic waste to composting would avoid harmful incineration emissions including CO, NOx, and VOCs (Abedin et al., 2025; Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives, 2019; Liu et al., 2021; Nubi et al., 2024).

Diversion of organic waste requires separation of waste streams, and cities with better collection and tracking networks often have more robust composting programs. Higher quality and more frequent reporting on waste generation and disposal worldwide could improve source separation and increase composting. Additionally, city-level and decentralized pilot programs allow for better control over feedstock collection and can bolster support for larger scale, centralized operations.

Multiple cities in Latin America and the Caribbean represent a resurgence in composting markets . In the 1960s and 1970s, composting facilities were built in cities across Mexico, El Salvador, Ecuador, Venezuela, and Brazil, but many closed due to high operational costs (Ricci-Jürgensen et al., 2020a). In 2018, 15% of waste was recycled or composted in Montevideo, Uruguay, and Bogotá and Medellín, Colombia, and 10% of waste was composted in Mexico City, Mexico, and Rosario, Argentina (Kaza et al., 2018).

Waste generation is increasing globally, with the largest increases projected to occur in sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and the Middle East and North Africa (Kaza et al., 2018). As waste generation doubles or triples in these regions, sustainable disposal methods will become more critical for human health and well-being.

In 2018, Ethiopia reported the highest organic waste percentage in sub-Saharan Africa at 85% of MSW, but no composting (World Bank, 2018). Organic waste percentages are high in other countries in the region, so composting could be a valuable method to handle the growing waste stream. In the Middle East & North Africa, 43% of countries reported composting as of 2018 (Kaza et al., 2018), indicating the presence of infrastructure that could be scaled up to handle increased waste in the future.

- Establish zero waste and OW diversion goals; incorporate them into local or national climate plans and soil health and conservation policies.

- Ensure public procurement uses local compost when possible.

- Participate in consultations with farmers, businesses, and the public to determine where to place plants, how to use compost, pricing, and how to roll out programs.

- Establish or improve existing centralized composting facilities, collection networks, and storage facilities.

- Establish incentives and programs to encourage both centralized and decentralized composting.

- Work with farmers, local gardeners, the private sector, and local park systems to develop markets for compost.

- Invest in source separation education and waste separation technology that enhances the quality of final compost products.

- Regulate the use of waste separation technologies to prioritize source separation of waste and the quality of compost products.

- Ensure low- and middle-income households are served by composting programs with particular attention to underserved communities such as multi-family buildings and rural households.

- Enact extended producer responsibility approaches that hold producers accountable for waste.

- Create demonstration projects to show the effectiveness and safety of finished compost.

- Ensure composting plants are placed as close to farmland as possible and do not adversely affect surrounding communities.

- Streamline permitting processes for centralized compost facilities and infrastructure.

- Establish laws or regulations that require waste separation as close to the source as possible, ensuring the rules are effective and practical.

- Establish zoning policies that support both centralized and decentralized composting efforts, including at the industrial, agricultural, community, and backyard scales.

- Establish fees or fines for OW going to landfills; use funds for composting programs.

- Use financial instruments such as taxes, subsidies, or exemptions to support infrastructure, participation, and waste separation.

- Partner with schools, community gardens, farms, nonprofits, women’s groups, and other community organizations to promote composting and teach the importance of waste separation.

- Establish one-stop-shop educational programs that use online and in-person methods to teach how to separate waste effectively and why it’s important.

- If composting is not possible or additional infrastructure is needed, consider methane digesters as alternatives to composting.

- Create, support, or join certification programs that verify the quality of compost and/or verify food waste suppliers such as hotels, restaurants, and cafes.

Further information:

- Container Based Sanitation Alliance

- Composting and climate action plans: a guide for local solutions. Institute for Local Self-Reliance (2024)

- Government relations and public policy job function action guide. Project Drawdown (2022)

- Legal job function action guide. Project Drawdown (2022)

- Work with policymakers and local communities to establish zero-waste and OW diversion goals for local or national climate plans.

- Participate in consultations with farmers, policymakers, businesses, and the public to determine where to place plants, how to use compost, pricing, and how to roll out programs.

- Work with farmers, local gardeners, the private sector, and local park systems to create quality supply streams and develop markets for compost.

- Invest in source separation education and waste separation technology that enhances the quality of final compost products.

- Establish one-stop-shop educational programs that use online and in-person methods to teach how to separate waste effectively and why that’s important.

- Ensure low- and middle-income households are served by composting programs with particular attention to underserved communities such as multi-family buildings and rural households.

- Create demonstration projects to show the effectiveness and safety of finished compost.

- Ensure composting plants are placed as close to farmland as possible and do not adversely affect surrounding communities.

- Take advantage of financial incentives such as subsidies or exemptions to set up centralized composting infrastructure, increase participation, and improve waste separation.

- Partner with schools, community gardens, farms, nonprofits, women’s groups, and other community organizations to promote composting and teach the importance of waste separation.

- Consider partnerships through initiatives such as sister cities to share innovation and develop capacity.

- If additional infrastructure is needed, consider methane digesters as alternatives to composting.

- Create, support, or join certification programs that verify the quality of compost and/or verify food waste suppliers such as hotels, restaurants, and cafes.

Further information:

- Container Based Sanitation Alliance

- Composting and climate action plans: a guide for local solutions. Institute for Local Self-Reliance (2024)

- Establish zero-waste and OW diversion goals; incorporate the goals into corporate net-zero strategies.

- Ensure procurement uses strategies to reduce FLW at all stages of the supply chain; consider using the Food Loss and Waste Protocol.

- Ensure corporate procurement and facilities managers use local compost when possible.

- Participate in consultations with farmers, policymakers, and the public to determine where to place plants, how to use compost, pricing, and how to roll out programs.

- Work with farmers, local gardeners, the private sector, and local park systems to develop markets for compost.

- Offer employee pre-tax benefits on materials to compost at home or participate in municipal composting programs.

- Offer financial services, including low-interest loans, microfinancing, and grants, to support composting initiatives.

- Support extended producer responsibility approaches that hold producers accountable for waste.

- Educate employees on the benefits of composting, include them in companywide waste diversion initiatives, and encourage them to use and advocate for municipal composting in their communities. Clearly label containers and signage for composting.

- Partner with schools, community gardens, farms, nonprofits, women’s groups, and other community organizations to promote composting and teach the importance of waste separation.

- Create, support, or join certification programs that verify the quality of compost and/or verify food waste suppliers such as hotels, restaurants, and cafes.

Further information:

- Container Based Sanitation Alliance

- Composting and climate action plans: a guide for local solutions. Institute for Local Self-Reliance (2024)

- Climate solutions at work. Project Drawdown (2021)

- Drawdown-aligned business framework. Project Drawdown (2021)

- Help policymakers establish zero-waste and OW diversion goals; help incorporate them into local or national climate plans.

- Ensure organizational procurement uses local compost when possible.

- Help administer, fund, or promote local composting programs.

- Help gather data on local OW streams, potential markets, and comparisons of alternative uses such as methane digesters.

- Participate in consultations with farmers, policymakers, businesses, and the public to determine where to place plants, how to use compost, pricing, and how to roll out programs.

- Work with farmers, local gardeners, the private sector, and local park systems to develop markets for compost.

- Help ensure low- and middle-income households are served by composting programs with particular attention to underserved communities such as multi-family buildings and rural households.

- Advocate for extended producer responsibility approaches that hold producers accountable for waste.

- Advocate for laws or regulations that require waste separation as close to the source as possible, ensuring the rules are effective and practical.

- Create demonstration projects to show the effectiveness and safety of finished compost.

- Establish one-stop-shop educational programs that use online and in-person methods to teach how to separate waste effectively and why that’s important.

- Partner with schools, community gardens, farms, nonprofits, women’s groups, and other community organizations to promote composting and teach the importance of waste separation.

- Create, support, or join certification programs that verify the quality of compost and/or verify food waste suppliers such as hotels, restaurants, and cafes.

Further information:

- Container Based Sanitation Alliance

- Composting and climate action plans: a guide for local solutions. Institute for Local Self-Reliance (2024)

- Ensure relevant portfolio companies separate waste streams, contribute to compost programs, and/or use finished compost.

- Invest in companies developing composting programs or technologies that support the process, such as equipment, circular supply chains, and consumer products.

- Fund start-ups or existing companies that are improving waste separation technology that enhances the quality of final compost products.

- Offer financial services, including low-interest loans, microfinancing, and grants, to support composting initiatives.

- Invest in companies that adhere to extended producer responsibility or encourage portfolio companies to adopt the policies.

Further information:

- Container Based Sanitation Alliance

- Composting and climate action plans: a guide for local solutions. Institute for Local Self-Reliance (2024)

- Help policymakers establish zero-waste and OW diversion goals; help incorporate them into local or national climate plans.

- Advocate for businesses to establish time-bound and transparent zero-waste and OW diversion goals.

- Advocate for extended producer responsibility approaches that hold producers accountable for waste.

- Provide financing and capacity building for low- and middle-income countries to establish composting infrastructure and programs.

- Help administer, fund, or promote composting programs.

- Invest in companies developing composting programs or technologies that support the process, such as equipment, circular supply chains, and consumer products.

- Fund startups or existing companies that are improving waste separation technology that enhances the quality of final compost products.

- Incubate and fund mission-driven organizations and cooperatives that are advancing OW composting.

- Offer financial services, including low-interest loans, microfinancing, and grants, to support composting initiatives.

- Participate in consultations with farmers, policymakers, businesses, and the public to determine where to place plants, how to use compost, pricing, and how to roll out programs.

- Work with farmers, local gardeners, the private sector, and local park systems to develop markets for compost.

- Help ensure low- and middle-income households are served by composting programs, with particular attention to underserved communities such as multifamily buildings and rural households.

- Advocate for laws or regulations that require waste separation as close to the source as possible, ensuring the rules are effective and practical.

- Create demonstration projects to show the effectiveness and safety of finished compost.

- Research and enact effective composting promotional strategies.

- Establish one-stop-shop educational programs that use online and in-person methods to teach how to separate waste effectively and why that’s important.

- Partner with schools, community gardens, farms, nonprofits, women’s groups, and other community organizations to promote composting and teach the importance of waste separation.

- Create, support, or join certification programs that verify the quality of compost and/or verify food waste suppliers such as hotels, restaurants, and cafes.

Further information:

- Container Based Sanitation Alliance

- Composting and climate action plans: a guide for local solutions. Institute for Local Self-Reliance (2024)

- Participate in and promote centralized, community, or household composting programs, if available, and carefully sort OW from other waste streams.

- If no centralized composting system exists, work with local experts to establish household and community composting systems.

- Help policymakers establish zero-waste and OW diversion goals; help incorporate them into local or national climate plans.

- Start cooperatives that provide services and/or equipment for composting.

- Participate in consultations with farmers, policymakers, businesses, and the public to determine where to place plants, how to use compost, pricing, and how to roll out programs.

- Help gather data on local OW streams, potential markets, and comparisons of alternative uses such as methane digesters.

- Help develop waste separation technology that enhances the quality of final compost products and/or improve educational programs on waste separation.

- Develop innovative governance models for local composting programs; publicly document your experiences.

- Work with farmers, local gardeners, the private sector, and local park systems to develop markets for compost.

- Advocate for extended producer responsibility approaches that hold producers accountable for waste.

- Advocate for laws or regulations that require waste separation as close to the source as possible, ensuring the rules are effective and practical.

- Create demonstration projects to show the effectiveness and safety of finished compost.

- Create, support, or join certification programs that verify the quality of compost.

- Research various governance models for local composting programs and outline options for communities to consider.

- Research and enact effective composting campaign strategies.

- Create, support, or join certification programs that verify the quality of compost and/or verify food waste suppliers such as hotels, restaurants, and cafes.

Further information:

- Container Based Sanitation Alliance

- Composting and climate action plans: a guide for local solutions. Institute for Local Self-Reliance (2024)

- Quantify estimates of OW both locally and globally; estimate the associated potential compost output.

- Improve waste separation technology to improve the quality of finished compost.

- Create tracking and monitoring software for OW streams, possible uses, markets, and pricing.

- Research the application of AI and robotics for optimal uses of OW streams, separation, collection, distribution, and uses.

- Research various governance models for local composting programs and outline options for communities to consider.

- Research effective composting campaign strategies and how to encourage participation from individuals.

Further information:

- Container Based Sanitation Alliance

- Composting and climate action plans: a guide for local solutions. Institute for Local Self-Reliance (2024)

- Participate in and promote centralized composting programs, if available, and carefully sort OW from other waste.

- If no centralized composting system exists, work with local experts to establish household and community composting systems.

- Participate in consultations with farmers, policymakers, and businesses to determine where to place plants, how to use compost, pricing, and how to roll out programs.

- Take advantage of educational programs, financial incentives, employee benefits, and other programs that facilitate composting.

- Advocate for extended producer responsibility approaches that hold producers accountable for waste.

- Advocate for laws or regulations that require waste separation, ensuring the rules are effective and practical.

- Partner with schools, community gardens, farms, nonprofits, women’s groups, and other community organizations to promote composting and teach the importance of waste separation.

- Create, support, or join certification programs that verify the quality of compost and/or verify food waste suppliers such as hotels, restaurants, and cafes.

Further information:

- Container Based Sanitation Alliance

- Composting and climate action plans: a guide for local solutions. Institute for Local Self-Reliance (2024)

- Unlocking on-farm composting: key drivers in Mexico City's peri-urban areas. Cotler et al. (2025)

- Composting and climate action plans: a guide for local solutions. Institute for Local Self-Reliance (2024)

- Does exposure enhance interest? An analysis of composting exposure on interest in household waste management. Rahman et al. (2025)

- How can public policy advance the composting industry? Truelove (2023)

- CCET guideline series on intermediate municipal solid waste treatment technologies: composting. UNEP (2020)

- Growing community-based composting programs in China. Xue et al. (2025)

Consensus of effectiveness as a climate solution: High

Composting reduces OW, prevents pollution and GHG emissions from landfilled OW, and creates soil amendments that can reduce the use of synthetic fertilizers (Kaza et al., 2018; Manea et al., 2024). Although we do not quantify carbon sequestration from compost use in this analysis, a full life-cycle analysis that includes application could result in net negative emissions for composting (Morris et al., 2013).

Globally, the waste sector was responsible for an estimated 3.9% of total global GHG emissions in 2023, and solid waste management represented 36% of those emissions (IPCC, 2023; UNEP, 2024). Emissions estimates based on satellite and field measurements from landfills or direct measurements of carbon content in food waste can be significantly higher than IPCC Tier 1-based estimates. Reviews of global waste management estimated that food loss and food waste account for around 6% of global emissions or approximately 2.8 Gt CO₂‑eq/yr (Wilson et al., 2024; Zhu et al., 2023). Facility-scale composting reduces emissions 38–84% relative to landfilling (Perez et al., 2023), and monitoring and managing the moisture content, aeration, and carbon to nitrogen ratios can further reduce emissions (Ayilara et al., 2020).

Unclear legislation and regulation for MSW composting can prevent adoption, and there is not a one-size-fits-all approach to composting (Cao et al., 2023). Regardless of the method used, composting converts OW into a nutrient-rich resource and typically reduces incoming waste volumes 40–60% in the process (Cao et al., 2023; Kaza et al., 2018). A comparative cost and energy analysis of MSW components highlighted that while composting adoption varies geographically and economically, environmental benefits also depend on geography and income (Zaman, 2016). Food and green waste percentages of MSW are higher in lower-resourced countries than in high-income countries due to less packaging, and more than one-third of waste in high-income countries is recovered through recycling and composting (Kaza et al., 2018).

The results presented in this document summarize findings from 22 reports, 31 reviews, 12 original studies, two books, nine web articles, one fact sheet, and three data sets reflecting the most recent evidence for more than 200 countries and territories.

Global MSW Generation and Disposal

Analysis of MSW in this section is based on the 2018 What a Waste 2.0 global dataset and report as well as the references cited in the report (Kaza et al., 2018; World Bank 2018). In 2018, approximately 2 Gt of waste was generated globally. Most of that went to landfills (41%) and open dumps (22%). Out of 217 countries and territories, 24 sent more than 80% of all MSW to landfills and 3 countries reported landfilling 100% of MSW. The average across all countries/territories was 28% of MSW disposed of in landfills. Both controlled and sanitary landfills with gas capture systems are included in the total landfilled percentage.

Approximately 13% of MSW was treated through recycling and 13% through incineration, but slightly more waste was incinerated than recycled per year. Incineration was predominately used in upper-middle and high-income countries with negligible amounts of waste incinerated in low- and lower-middle income countries.

Globally, only about 5% of MSW was composted and nearly no MSW was processed via methane digestion. However, OW made up nearly 40% of global MSW, so most OW was processed through landfilling, open dumping, and incineration all of which result in significant GHG emissions and pollution. There is ample opportunity to divert more OW from polluting disposal methods toward composting. Due to lack of data on open dumping, and since incineration only accounts for 1% of global GHG emissions, we chose landfilling as our baseline disposal method for comparison.

In addition to MSW, other waste streams include medical waste, e-waste, hazardous waste, and agricultural waste. Global agricultural waste generation in 2018 was more than double total MSW (Kaza et al., 2018). Although these specialized waste streams are treated separately from MSW, integrated waste management systems with high-quality source separation programs could supplement organic MSW with agricultural waste. Rather than being burned or composted on-farm, agricultural waste can provide bulking materials that are critical for maintaining moisture levels and nutrient balance in the compost pile, as well as scaling up composting operations.

Details of a Composting System and Process

Successful centralized composting starts with collection and separation of OW from other waste streams, ideally at the source of waste generation. Financial and regulatory barriers can hinder creation or expansion of composting infrastructure. Composting systems require both facilities and robust collection networks to properly separate OW from nonbiodegradable MSW and transport OW to facilities. Mixed waste streams increase contamination risks with incoming feedstocks, so separation of waste materials at the source of generation is ideal.

Establishing OW collection presents a financial and logistical barrier to increased composting adoption (Kawai et al., 2020; Kaza et al., 2018). However, when considering a full cost-chain analysis that includes collection, transportation, and treatment, systems that rely on source-separated OW can be more cost-effective than facilities that process mixed organics.

OW and inorganic waste can also be sorted at facilities manually or mechanically with automated techniques including electromagnetic separation, ferrous metal separation, and sieving or screening (Kawai et al., 2020). Although separation can be highly labor-intensive, it’s necessary to remove potential contaminants, such as plastics, heavy metals, glass, and other nonbiodegradable or hazardous waste components (Kawai et al., 2020; Manea et al., 2024). After removing contaminants, organic materials are pre-processed and mixed to achieve the appropriate combination of water, oxygen, and solids for optimal aerobic conditions during the composting process.

Regardless of the specific composting method used, aerobic decomposition is achieved by monitoring and balancing key parameters within the compost pile. Key parameters are moisture content, temperature, carbon-to-nitrogen ratio, aeration, pH, and porosity (Cao et al., 2023; Kawai et al., 2020; Manea et al., 2024). The aerobic decomposition process can be split into distinct stages based on whether mesophilic (active at 20–40 oC) or thermophilic (active at 40–70 oC) bacteria and fungi dominate. Compost piles are constructed to allow for sufficient aeration while optimizing moisture content (50–60%) and the initial carbon-to-nitrogen ratio (25:1–40:1), depending on composting method and feedstocks (Amuah et al., 2022; Manea et al, 2024). Optimal carbon-to-nitrogen ratios are achieved through appropriate mixing of carbon-rich “brown” materials, such as sawdust or dry leaves, with nitrogen-rich “green” materials, such as food waste or manure (Manea et al., 2024). During the thermophilic stage, temperatures exceeding 62 oC are necessary to kill most pathogens and weed seeds (Amuah et al., 2022; Ayilara et al., 2020).

Throughout the composting process key nutrients (nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, magnesium, and sodium), are mineralized and mobilized and microorganisms release GHGs and heat as by-products of their activity (Manea et al., 2024; Nordahl et al., 2023). Water is added iteratively to maintain moisture content and temperature in the optimal ranges, and frequent turning and aeration are necessary to ensure microorganisms have enough oxygen. Without the proper balance of oxygen and water, anaerobic conditions can lead to higher methane emissions (Amuah et al., 2022; Manea et al., 2024). Although CO₂, methane, and nitrous oxide are released during the process, these emissions are significantly lower than associated emissions from landfilling (Ayilara et al., 2020; Cao et al., 2023; FAO, 2019; Perez et al., 2023).

Once aerobic decomposition is completed, compost goes through a maturation stage where nutrients are stabilized before finished compost can be sold or used as a soil amendment. In stable compost, microbial decomposition slows until nutrients no longer break down, but can be absorbed by plants. Longer maturation phases reduce the proportion of soluble nutrients that could potentially leach into soils.

The baseline waste management method of landfilling OW is cheaper than composting; however it also leads to significant annual GHG emissions. Composting, although more expensive due to higher labor and operating costs, reduces emissions and produces a valuable soil amendment. Establishing a composting program can have significant financial risks without an existing market for finished compost products (Bogner et al., 2007; Kawai et al., 2020; UNEP, 2024).

Example Calculation of Achievable Adoption

In 2018, Austria had the highest composting rate of 31.2%, and Vietnam composted 15% of MSW (World Bank, 2018).

For low adoption, we assumed composting increases by 25% of the existing rate or until all OW in MSW is composted. In Austria, OW made up 31.4% of MSW in 2018, so the Adoption – Low composting rate was 31.4%. In Vietnam, the Adoption – Low composting rate came out to 18.75%, which is still less than the total OW percentage of MSW (61.9%).

For high adoption, we assumed that composting rates increase by 50% of the existing rate or until all OW in MSW is composted. So high adoption in Austria remains 31.4% (i.e., all OW generated in Austria is composted). In Vietnam, the high adoption composting rate increases to 22.5% but still doesn’t capture all OW generated (61.9% of MSW).

Deploy Alternative Refrigerants

This solution involves reducing the use of high-global warming potential (GWP) refrigerants, instead deploying lower-GWP refrigerants. High-GWP (>800 on a 100-yr basis) fluorinated gases (F-gases) are currently used as refrigerants in refrigeration, air conditioning, and heat pump systems. Over the lifetime of this equipment, refrigerants escape into the atmosphere where they contribute to climate change.

Leaked lower-GWP refrigerant gases trap less heat in the atmosphere than do higher-GWP gases, so using lower-GWP gases reduces the climate impact of refrigerant use. In our analysis, this solution is only deployed as new equipment replaces decommissioned equipment because alternative refrigerants cannot typically be retrofitted into existing systems.

Refrigerants are chemicals that can absorb and release heat as they move between gaseous and liquid states under changing pressure. In this solution, we considered their use in six applications: residential, commercial, industrial, and transport refrigeration as well as stationary and mobile air conditioning. Heat pumps double as heating sources, though they are included here with air conditioning appliances. Refrigerants are released to the atmosphere during manufacturing, transport, installation, operation, repair, and disposal of refrigerants and equipment. Deploy Alternative Insulation Materials covers the use of refrigerant chemicals to produce foams.

Climate impacts of emissions of refrigerants can be reduced by:

- using lower-GWP refrigerants

- reducing leaks during equipment manufacturing, transport, installation, use, and maintenance

- reclaiming refrigerant at end-of-life and destroying or recycling it

- using less refrigerant through efficiency improvements or reduction in demand.

This solution evaluated the use of lower-GWP refrigerants alone. Leak reduction and responsible disposal are covered in Improve Refrigerant Management. Lowering use of and demand for refrigerants – while outside the scope of these assessments – is the most effective way to reduce emissions.

Most refrigerants used in new equipment today are a group of F-gases called hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) (Figure 1). HFCs are GHGs and are typically hundreds to thousands of times more potent than CO₂ (Smith et al., 2021). Since high-GWP refrigerants are usually short-lived climate pollutants, their negative climate impacts tend to be concentrated in the near term (Shah et al., 2015). High-GWP HFC production and consumption are being phased down under the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol, but existing stock and production remains high worldwide (Amendment to the Montreal Protocol on Substances That Deplete the Ozone Layer, 2016; United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change [UNFCCC], 2023). Other types of refrigerants that deplete the ozone layer – including chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) — are also being phased out of new production and use globally (Montreal Protocol on Substances That Deplete the Ozone Layer, 1987; Figure 1).