Home

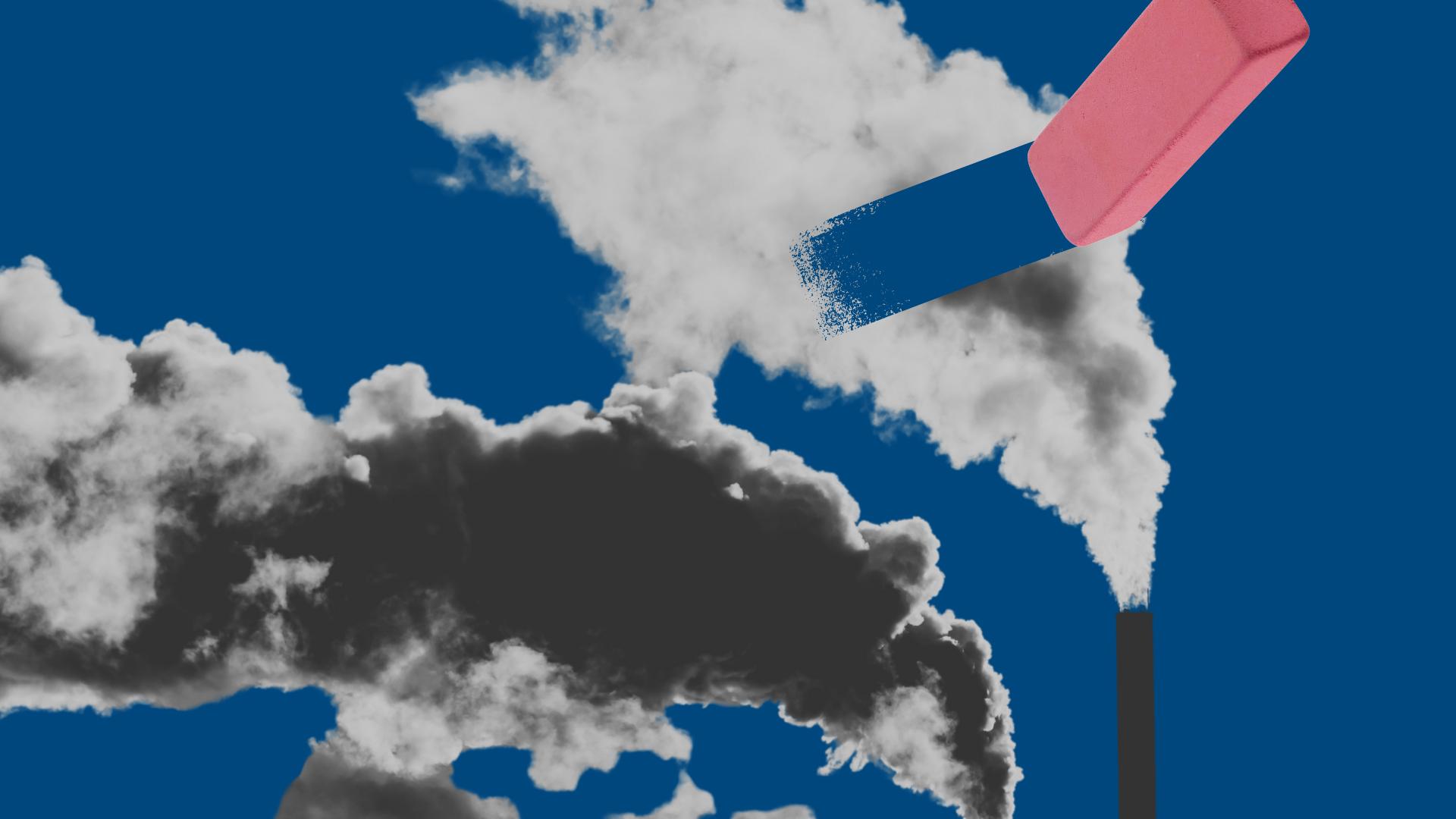

The World’s Leading Guide to Science-Based Climate Solutions

Image

Credit: Chokniti-Studio

Image

Credit: RyanJLane

Image

Credit: istock/PK24

Driving Bold Climate Action

Now more than ever, the world needs a strategic approach to addressing climate change. That’s where we come in. Project Drawdown is an independent, internationally trusted organization driving meaningful climate action by connecting people like you to science-based climate solutions and strategies.

News and Insights

Explore Climate Solutions

Nature-Based Carbon Removal

Deploy Silvopasture

FALO & Nature-Based Carbon Removal

Protect Forests: Temperate

FALO & Nature-Based Carbon Removal

Protect Coastal Wetlands: Seagrass ecosystems

Transportation

Mobilize Electric Bicycles: Private electric bicycles

FALO & Nature-Based Carbon Removal

Protect Forests: Boreal

FALO & Nature-Based Carbon Removal

Protect Peatlands: Tropical