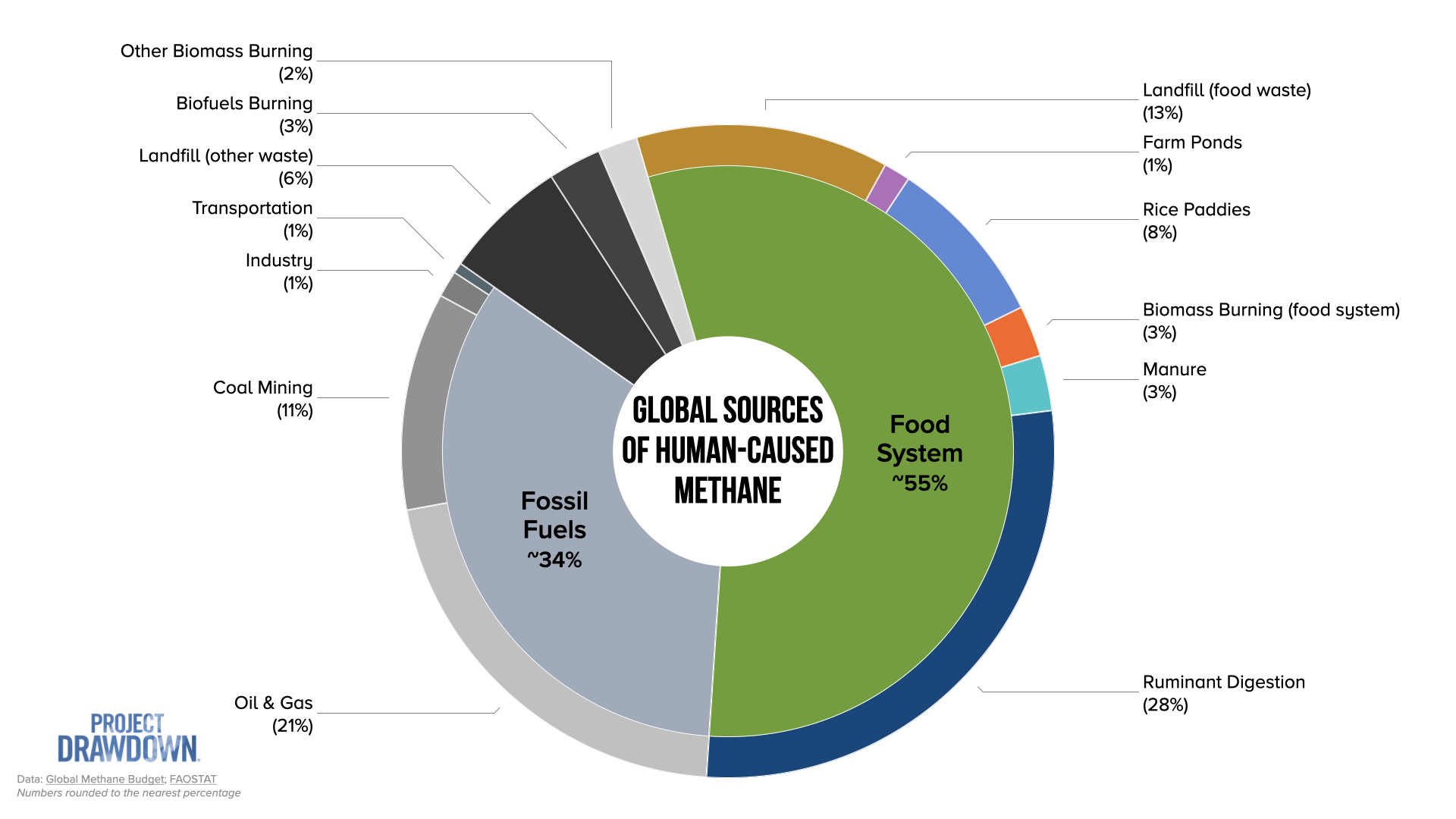

It’s fitting that methane is finally getting more attention. About one third of Earth’s warming to date has been from methane – a climate super pollutant 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide in the short term – and tackling its emissions is one of the most important and effective actions we can take to stabilize our climate. Humans are responsible for about 380 million tons of the gas each year. Although leaks from oil and gas infrastructure are a notorious source, emissions from agriculture and the broader food system are much larger. Yet they receive significantly less attention from the media, policymakers, and funders.

The food system contributes methane along the entire supply chain, from farm to landfill, including from cattle, manure, rice farming, biomass burning, and food waste. When combining all of these links in the chain together, it is responsible for over 210 million tons of methane, more than half of global human-caused emissions, making food systems the largest source of the superpollutant.

With support from the Global Methane Hub, Project Drawdown has used peer-reviewed research and the Drawdown Explorer to map hot spots of methane emissions across the global food system. Here are the four biggest sources of food-related methane, where they occur, and what solutions could help us curb emissions and limit planetary warming.

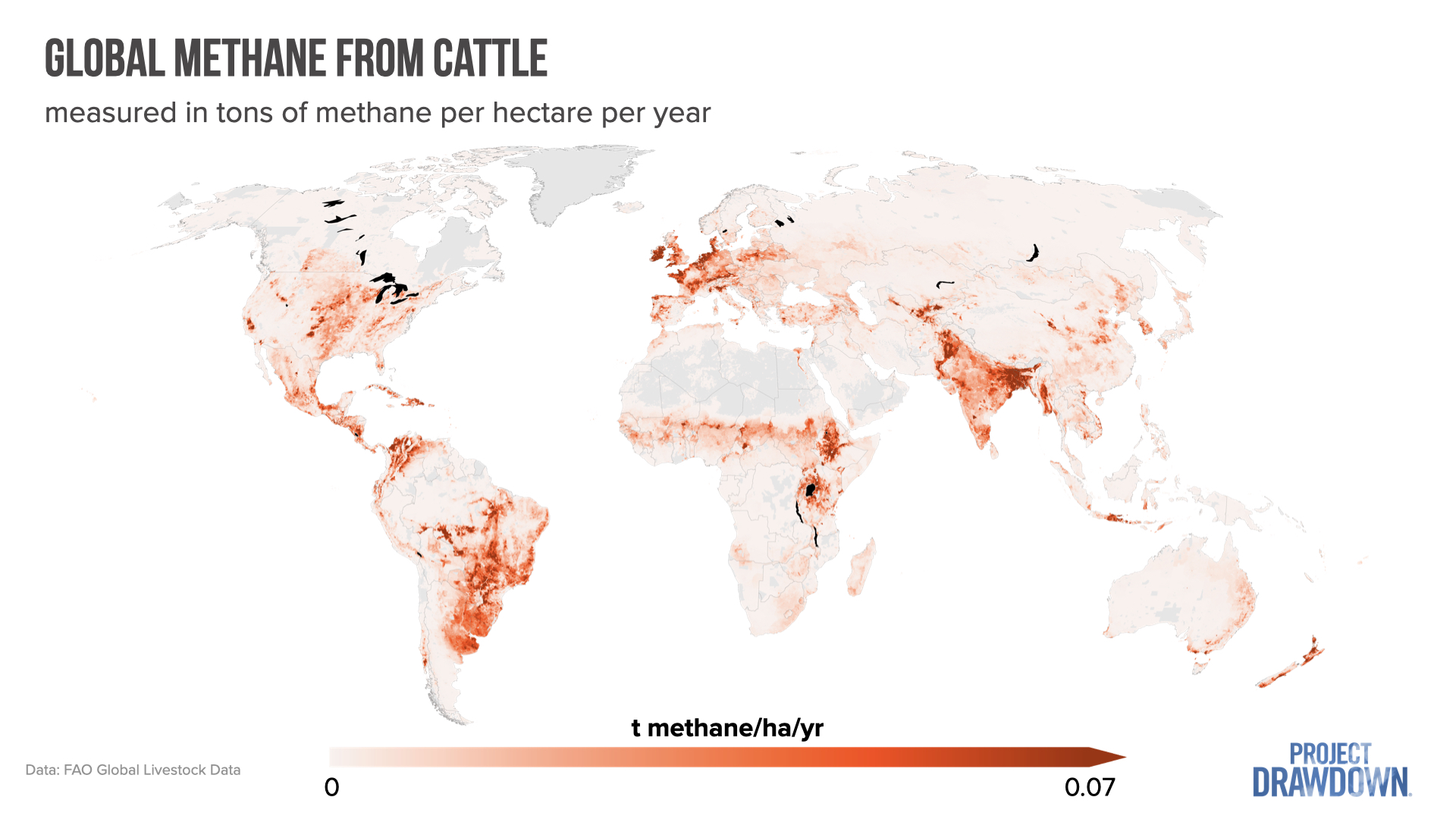

Burping Cows

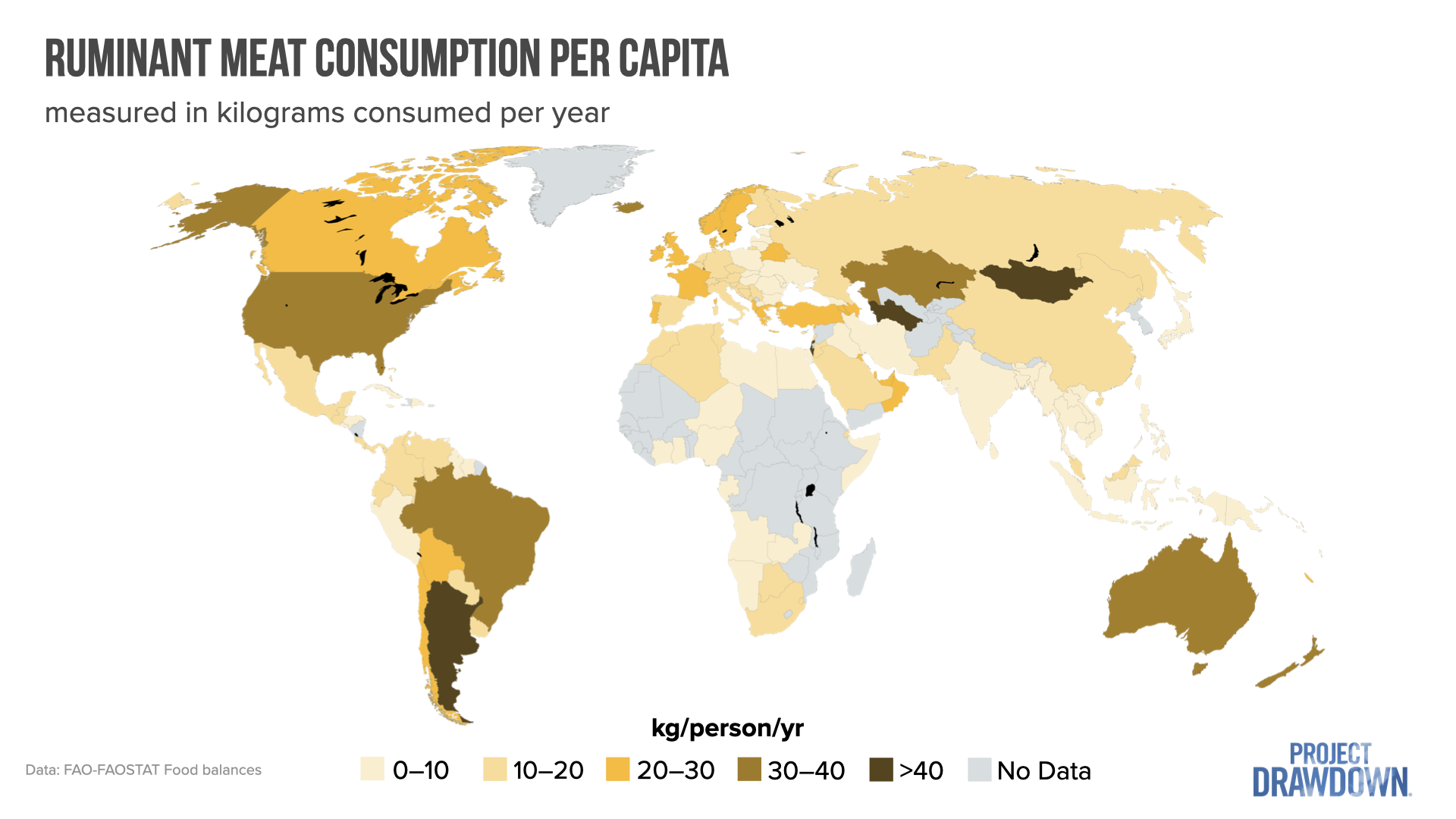

There are a lot of cattle raised for beef and dairy on Earth – about 1.5 billion of them each year. And when they burp, they emit methane. Ruminant livestock (including cattle, sheep, and goats) with multi-chambered stomachs can digest grasses and other biomass that humans can’t. But this digestion process – and the belching that comes with it – emits about 28% of human-caused methane emissions.

Eating less beef is the best way to reduce emissions from cattle. For the Improve Diets solution on the Drawdown Explorer, we evaluated the emissions savings from reducing beef (and other ruminant meat, such as lamb) consumption in high- and middle-income countries to a 100-gram (3.5-ounce) serving per week, which is estimated to be a healthy and sustainable level by an international team of scientists. We found that reducing beef consumption to this level could reduce global greenhouse gas emissions by 2.8 billion tons of carbon dioxide equivalents per year, which is more than half of the annual emissions of the U.S.

In addition to eating less beef, there are promising developments in feed additives that can reduce methane emissions from ruminants. Many feed additive compounds are still being researched to determine their efficacy and safety; however, at least one product, 3-NOP (3-nitrooxypropanol), has been shown to be effective and is approved for use in many countries. Still, due to the cost and the need to be administered daily, the use of feed additives is currently limited to more industrial production systems in high- and middle-income countries.

Rotting Food

Rotting food doesn’t just smell bad; when put in an oxygen-poor environment like a landfill, it readily generates methane. Using previously published data, we mapped methane emissions from food loss and waste and identified hot spots of emissions from landfills.

Globally, municipal solid waste is responsible for about 70 million tons of methane, and food waste contributes about 60% of these emissions. Depending on how landfills are managed, emissions can differ immensely. We found that the top 10 highest-emitting landfills account for 4% of all landfill emissions; the top 100 of the 9,625 landfills analyzed account for 15%.

Detecting leaks, implementing biocovers, and capturing methane are all solutions for reducing landfill emissions, which are calculated and illustrated on the Drawdown Explorer.

Burning Biomass

Burning biomass releases harmful pollutants and greenhouse gases into the air, including about 17 million tons of methane each year. One kind of biomass that is regularly burned is crop residues, the plant materials such as stalks, leaves, and seed husks that are left over after a crop is harvested. Many farmers burn crop residues in the field to remove weeds or to clear fields before the next planting.

On many farms, straw baling equipment can be used to harvest residues for off-farm use. When residues are baled or otherwise collected from the field, and where markets are developed, they can be used or sold for compost production, livestock feed and bedding, bioenergy applications, and feedstock for manufacturing paper and other products.

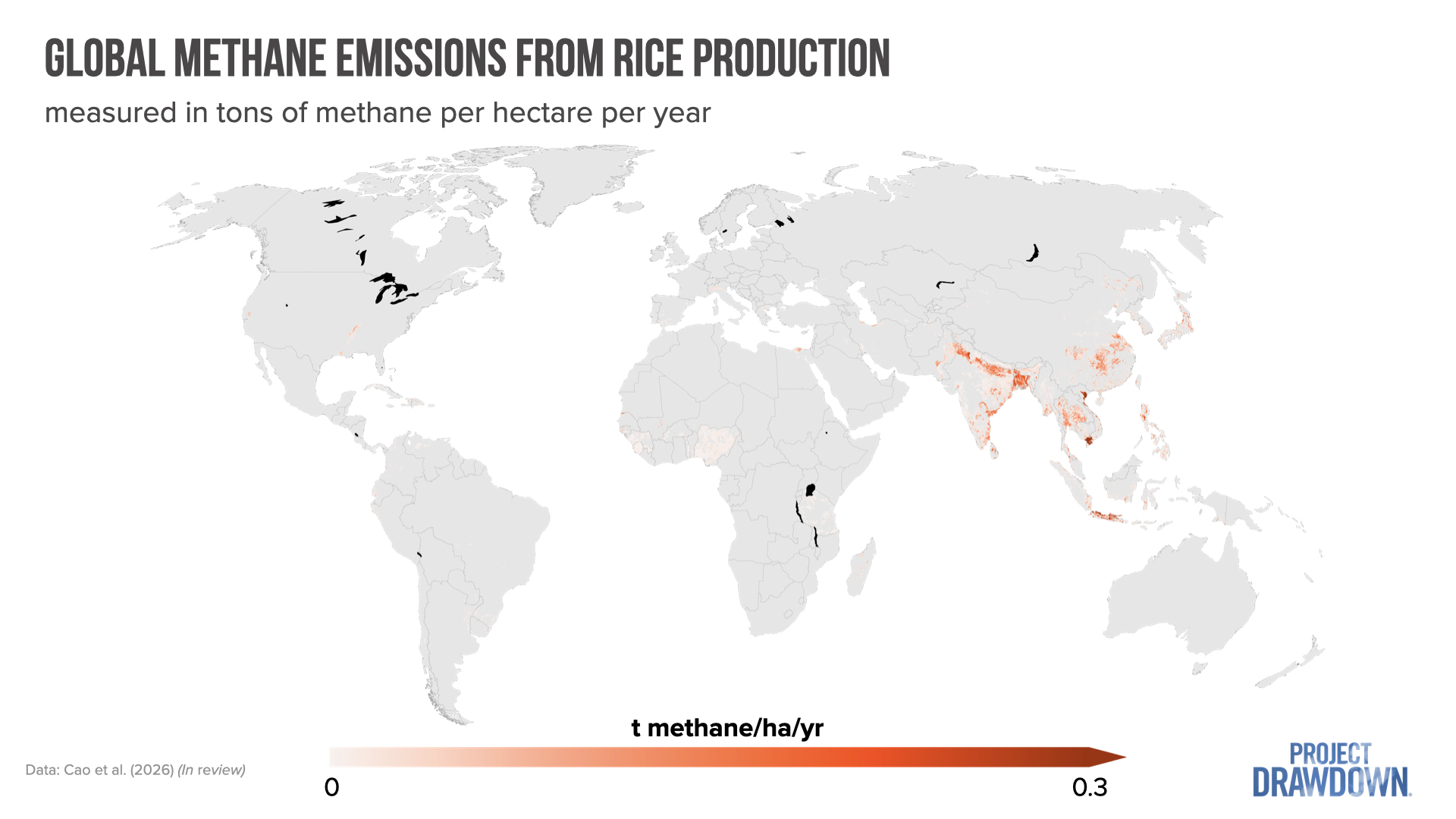

Flooded Rice Fields

Rice is a nutritious staple crop, but growing it produces 30 million tons of methane annually. Most rice is grown in flooded fields called paddies, where oxygen-poor conditions trigger methane production. Emissions from rice are disproportionately high in regions with multiple harvests per year and in regions that practice continuous flooding without draining their fields.

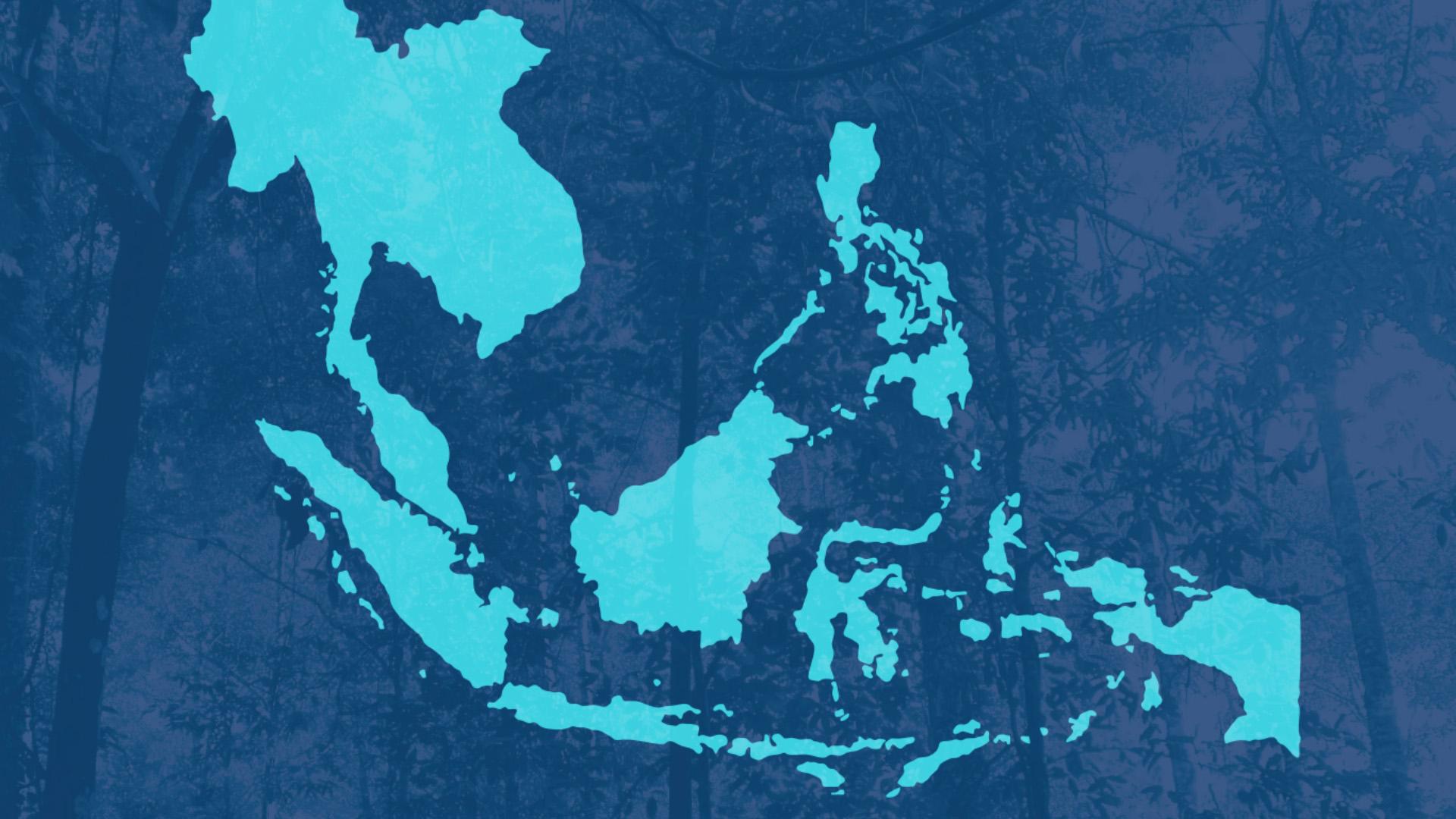

An international science team, including researchers at Project Drawdown, developed a new geospatial dataset of methane emissions from croplands. Their findings reinforce that rice fields generate the most greenhouse gases of any crop. Much of the emissions are concentrated in India and Southeast Asia, and to a lesser extent, along the Mississippi River Delta.

We used this dataset in a recent deep dive into emissions in Southeast Asia, and found that some of the highest-emitting rice fields are in the river deltas of Vietnam. Continuous flooding and triple cropping of fields in these deltas drive 10% of global rice methane emissions, yet Vietnam produces just 5% of the world’s rice. Moreover, we found that 20% of Vietnam’s rice fields were suitable for draining once or more per year – a practice called non-continuous flooding – which could cut rice-related emissions by 60% without reducing crop yields. The Improve Rice solution on the Drawdown Explorer provides estimates of emissions savings from switching to non-continuous flooding and improving fertilizer management on rice fields.

By mapping the potential effectiveness, adoption, costs, and impact of different climate solutions on the Drawdown Explorer, we have identified “hot spots” for climate action – regions where putting solutions into practice can maximize climate benefits.

This research enables us to guide philanthropies, businesses, and nonprofits toward the most effective climate solutions, so they can target action where and when it will lead to the greatest reduction in emissions.

The world has already lost far too much time in the race against climate change. Emergency brake climate solutions that reduce methane emissions, such as those enumerated here, can have a disproportionately fast impact after implementation, helping us get back on track. Methane is finally having its moment; we need the solutions that best address it to have their moment, too.

Emily Cassidy is an environmental scientist and writer, with expertise in agriculture, ecology, and land use. As a research associate at Project Drawdown, Emily evaluates the emissions mitigation potential of climate solutions in the food system.

Paul West, Ph.D., is an ecologist developing science-based solutions for sustaining a healthy planet for people and nature. At Project Drawdown, Paul assesses how climate solutions can create win-wins and trade-offs for conserving biodiversity, creating a sustainable food system, and otherwise improving planetary health and human well-being.

This work was published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license. You are welcome to republish it following the license terms.