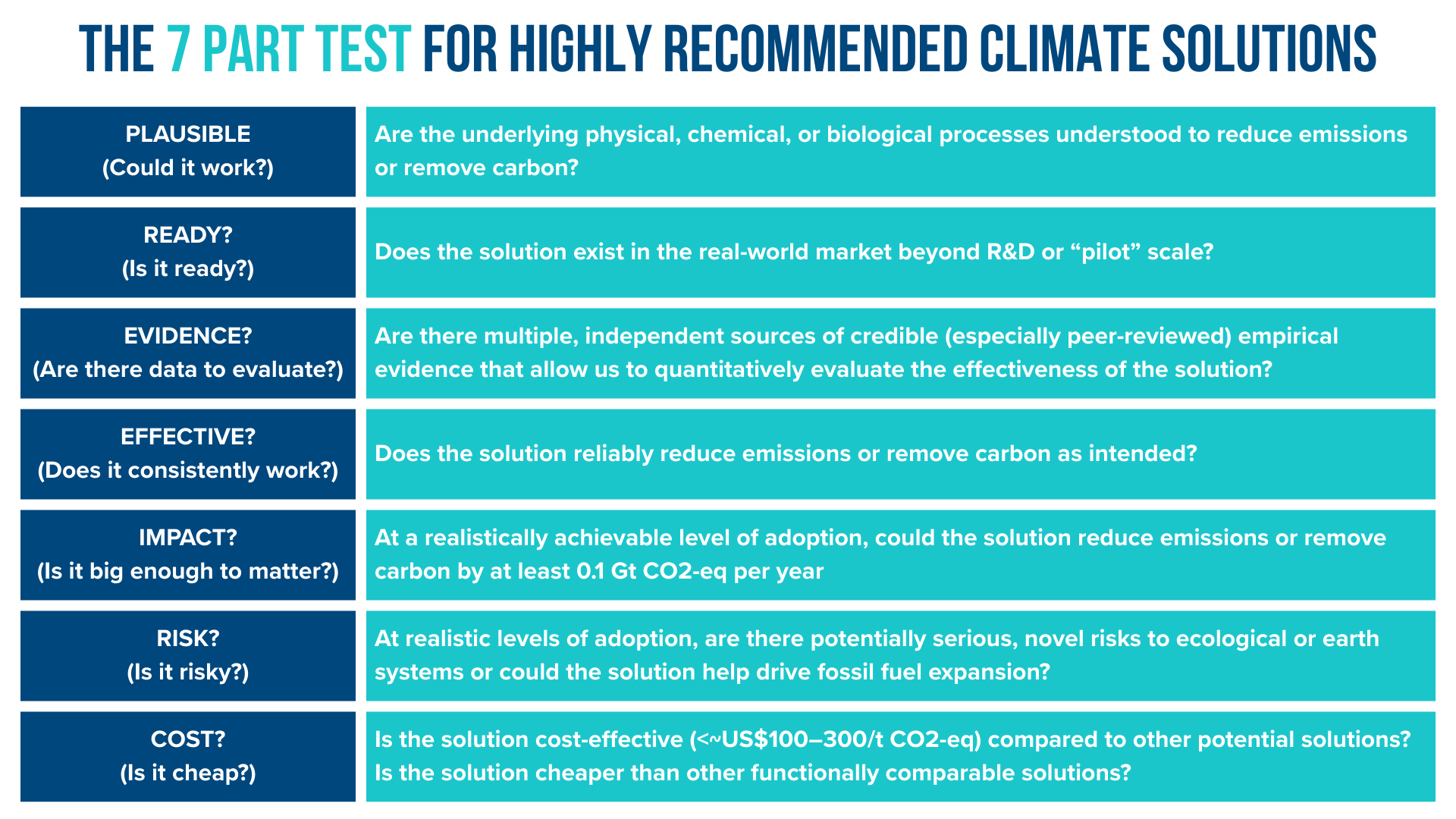

For every potential climate solution, we answered each of these questions as either “Yes” or “No,” with an occasional “Limited” or “Uncertain/Unknown” substituted when the answer was less clear. Then we developed rules to assign each solution into one of four categories – Highly Recommended, Worthwhile, Keep Watching, and Not Recommended – based on how it met each element of this test. Let’s look at each of these categories more closely.

The Most Effective, Promising, and Needed Climate Solutions

“Highly Recommended” climate solutions are the high-achievers that pass all seven parts of the test. These solutions are well-supported by the evidence, have a globally meaningful climate impact when scaled up, and are cost-effective methods for reducing emissions or removing carbon. While implementing the solution could have some adverse impacts or risks, it does not pose a serious threat to people, the planet, or the environment, nor will it drive the expansion of production and use of fossil fuels. Scaling up these effective, high-impact climate solutions, like using heat pumps or protecting forests, should be the highest priority in our efforts to rein in climate change.

Less Impactful Climate Solutions Still Worth Doing

“Worthwhile” solutions must pass all parts of the test except the Impact criterion. They are effective and ready to go, but even at a generous and achievable level of adoption, their likely global climate impact is below our threshold of 0.1 Gt CO₂‑eq

per year (~0.16% of current global emissions). These solutions are definitely worth doing, but given the urgency of the climate crisis and our need to drastically cut emissions now, they should not take precedence over more impactful “Highly Recommended” climate solutions. For example, improving the fuel efficiency of fishing vessels will reduce emissions, but since there are many more cars than fishing boats, prioritizing fuel efficiency for the former will deliver a greater climate impact.

Promising Climate Solutions Not Ready For Primetime

The next category, “Keep Watching,” is for potential solutions that, although they show promise on paper or even in pilot studies, are not quite ready for large-scale deployment. For this category, we look at readiness, evidence, effectiveness, and cost. If the solution is already in use, are there credible, quantitative data available to evaluate it? If there are data, does the solution consistently work as intended to reduce emissions or remove carbon?

For some solutions, such as protecting the seafloor, there are not enough data to evaluate the climate effects of disturbance or the effectiveness of protection. For others, such as enhanced rock weathering, results from multiple early deployments, while promising, have been inconsistent regarding the technology's reliability in durably removing carbon dioxide from the air. Cost can also be a decisional issue. For example, small modular nuclear reactors can produce large amounts of zero-carbon electricity, but they are much more expensive than other technologies such as wind, solar, batteries, and enhanced geothermal that can do the same.

We labeled these types of solutions as “Keep Watching” because, as they are further developed, tested, and deployed, there will be more evidence and data to evaluate them, and their costs may come down. In the next few years, some of these solutions will likely be promoted to either “Worthwhile” or “Highly Recommended.”

Climate “Solutions” Not Worth Pursuing

This brings us to the “Not Recommended” category. Among the more than 150 potential climate solutions on our list, there are several that concern us based on our research. After several intense discussions, we concluded there are two possible reasons to label a potential climate solution as “Not Recommended.”