How does the seafloor store carbon?

Despite an average depth of over 3,700 meters, the seafloor is closely connected to processes on land and in the ocean's surface waters. Most carbon in the seafloor is generated in the upper sunlit zones of the ocean by phytoplankton, including photosynthetic algae and bacteria. These organisms absorb CO₂ from the water and convert it into organic matter, some of which sinks and is eventually buried in seafloor sediments. A smaller amount of carbon enters the sea via rivers, groundwater, and dust. Incredibly, less than 1% of the carbon fixed by phytoplankton ends up sequestered in the seafloor, as most is degraded or transported away before it reaches the seabed. Though it might seem small, that fraction adds up over time, and once buried, seafloor carbon can remain locked away for millions of years if left undisturbed.

What are the major threats to seafloor carbon?

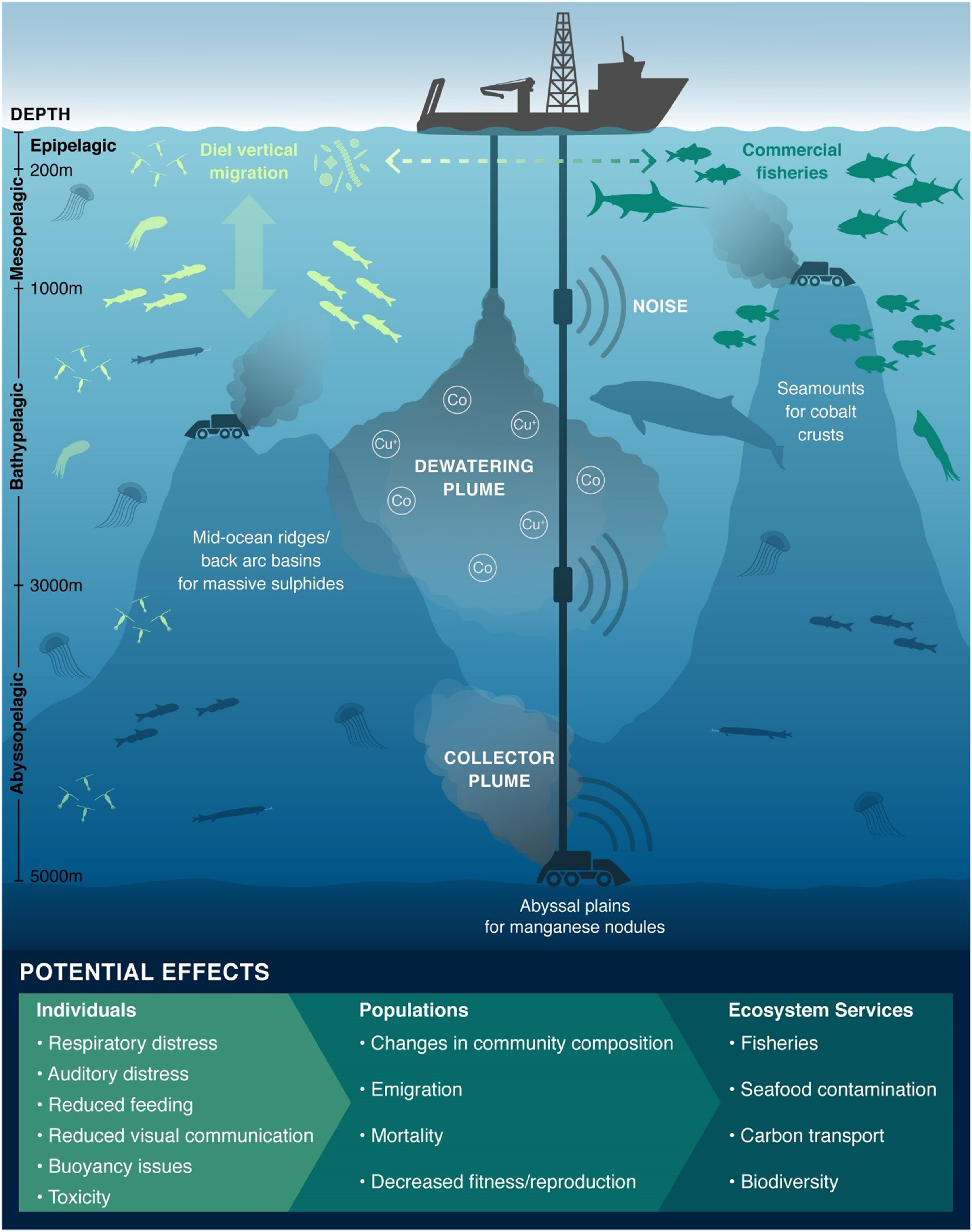

With any seafloor disturbance, the mobilization of sediment and stored carbon can result in CO₂ emissions through interconnected physical, biological, and chemical processes. Though much of the sediment resettles, some remains suspended long enough to be degraded, leading to a loss of stored carbon. As microbes break down this newly available carbon, they release CO₂ in the water column, which can eventually make its way to the atmosphere.

Currently, seafloor degradation is primarily caused by bottom fishing practices, such as trawling and dredging, which involve dragging heavy nets and cages along the seafloor, disturbing seafloor sediment. Other potential disturbances to seafloor carbon include undersea mining, offshore infrastructure, and telecommunications cables.