A certified “net zero” building, “climate neutral” building, or even a “climate positive” building does not mean a building without negative consequences for the climate or the environment. There are many certification schemes for getting to zero, and most of them will result in a much better building than if the designer and builder had used typical practices. I’ve written before about why that’s worth celebrating, even though net zero isn’t a very useful concept for an individual building. But it’s equally important to be honest about what such designations do and don’t mean.

Buildings (even the good ones!) drive emissions.

To claim “zero” for a building, even the most highly efficient one, you first need to reduce emissions as much as possible. That’s the good part of these certifications.

There are many ways our buildings cause emissions, all of which are detailed in a webinar I gave last year. They include burning fossil fuels; using electricity, refrigerants, and manufactured materials; transporting people and materials to and from the building; and producing waste. Look around at the building you're currently in. How many of these can you see right now? I’m confident it’s more than zero.

Offsetting doesn’t erase those emissions.

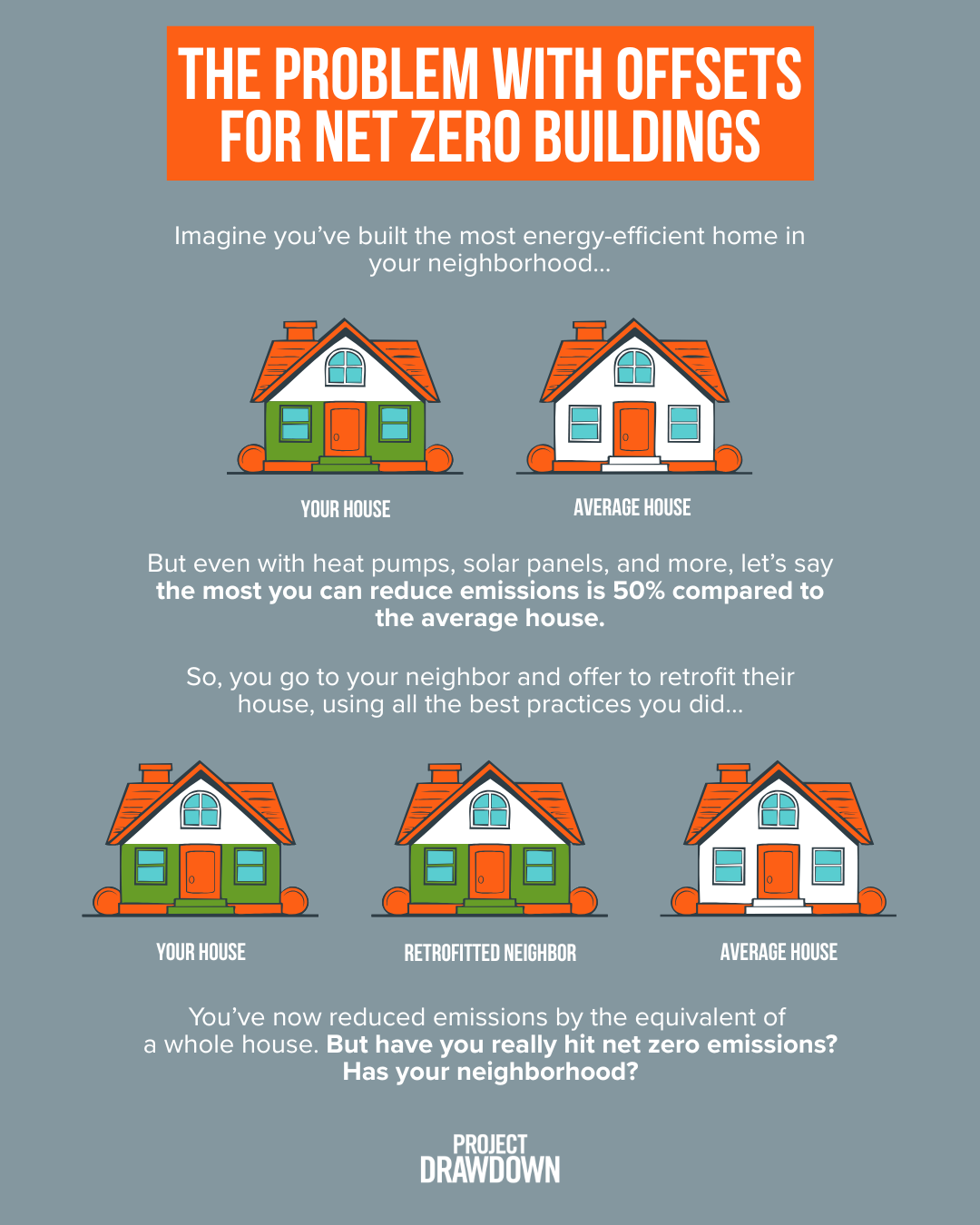

For the emissions remaining after you’ve cut as much as you can, “zero” claims rely on some combination of narrowing the scope of the emissions to be addressed or offsetting your actual emissions.

Narrowing the scope might mean you only address the on-site emissions, or that you only look at emissions due to the building’s energy consumption and ignore emissions from industry and transportation. Estimating all the emissions associated with a building throughout its lifetime is extremely tricky. It requires deep expertise and a lot of time to do a life cycle assessment that captures all the environmental impacts of a building. And even the best life cycle assessments will include a lot of uncertainty. It makes sense to focus on what you can meaningfully measure, given the available expertise, data, and budget for studying a building’s emissions. But your building isn’t zero emissions even if, for example, you’ve been able to cut all of your on-site emissions.

Offsetting emissions by paying for someone else to cut their emissions, produce more renewable energy, or support the Earth’s natural carbon sinks does not make your building’s emissions go away – it’s more like shuffling around the math than truly mitigating your impact.