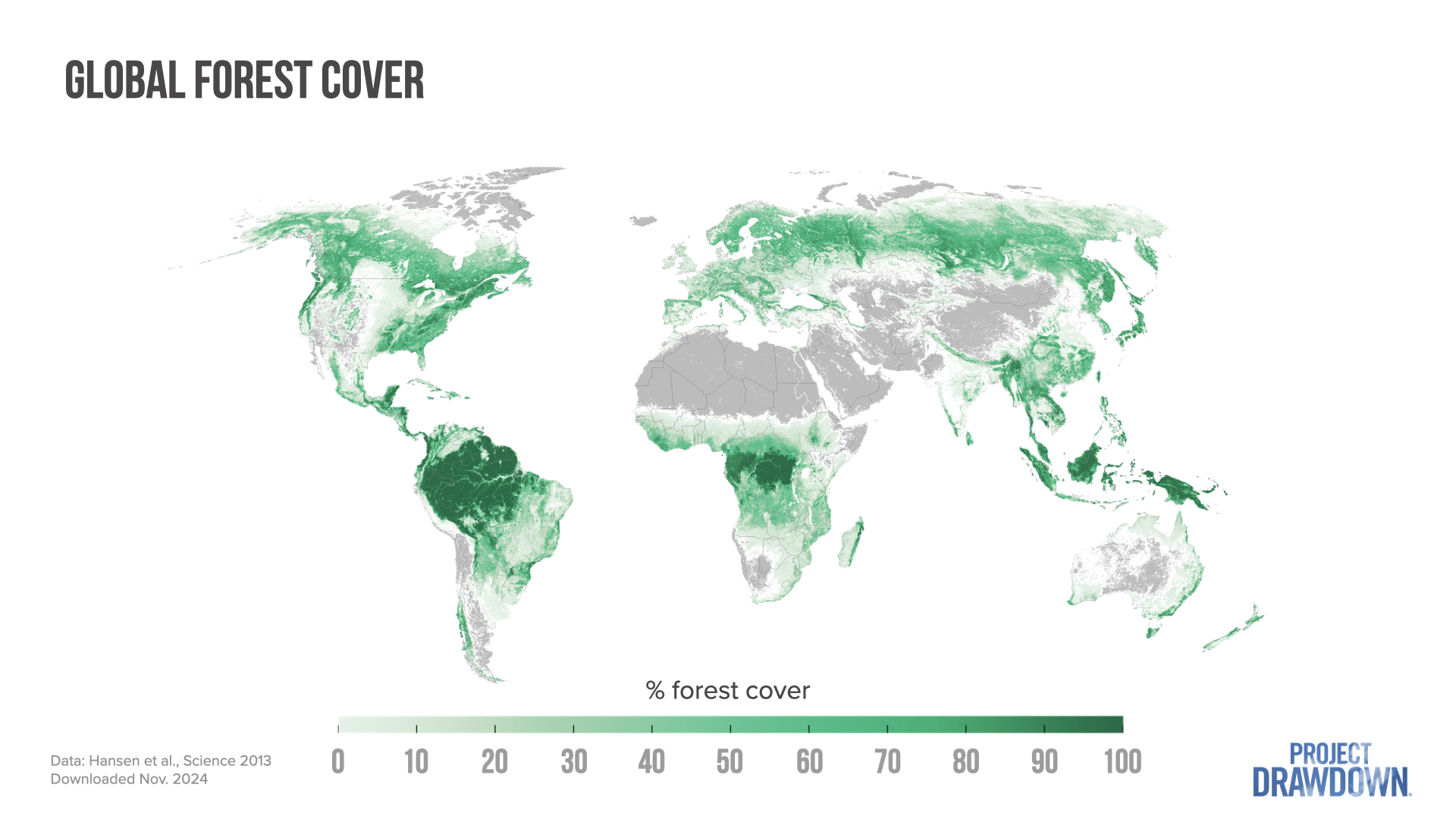

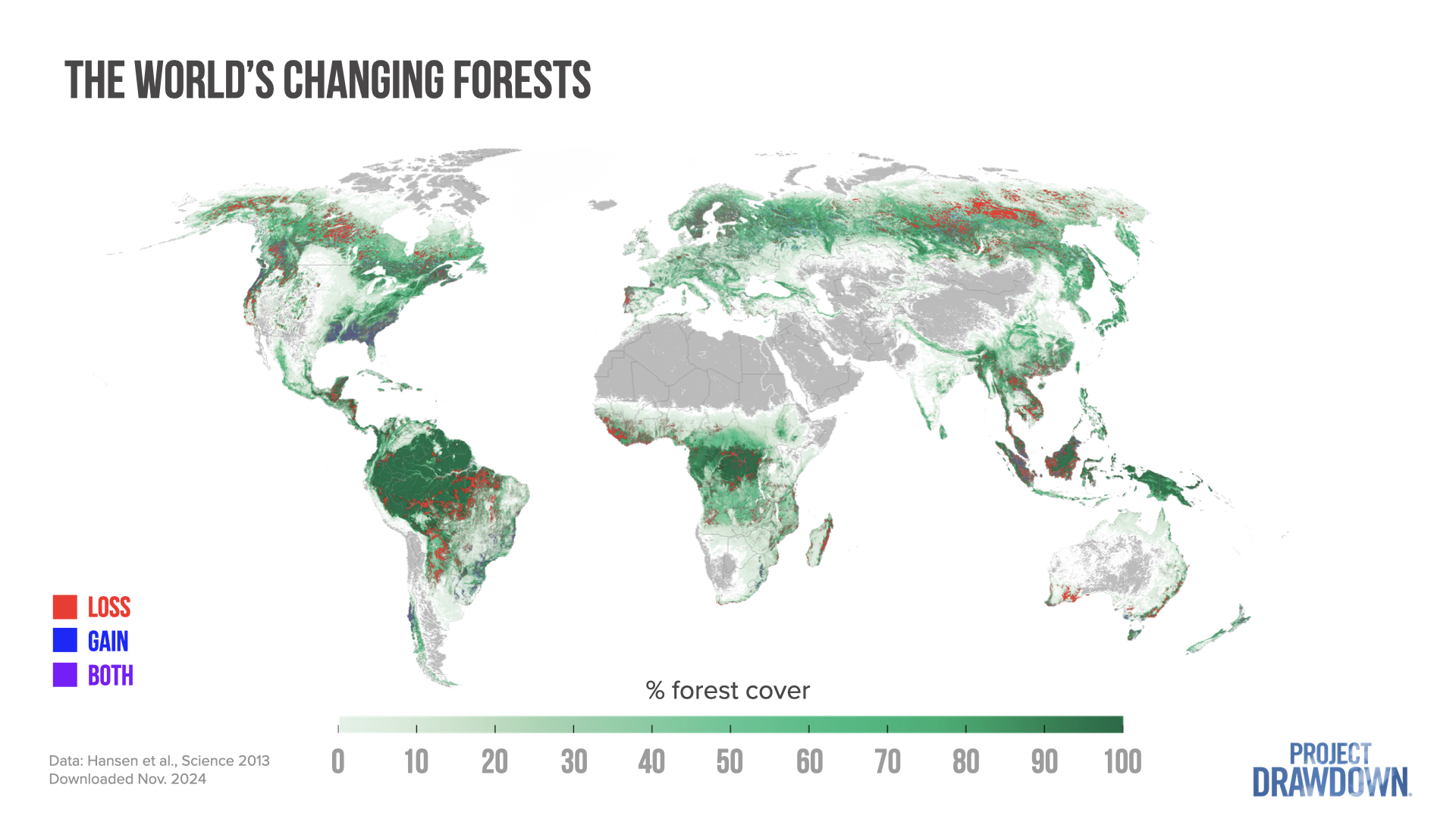

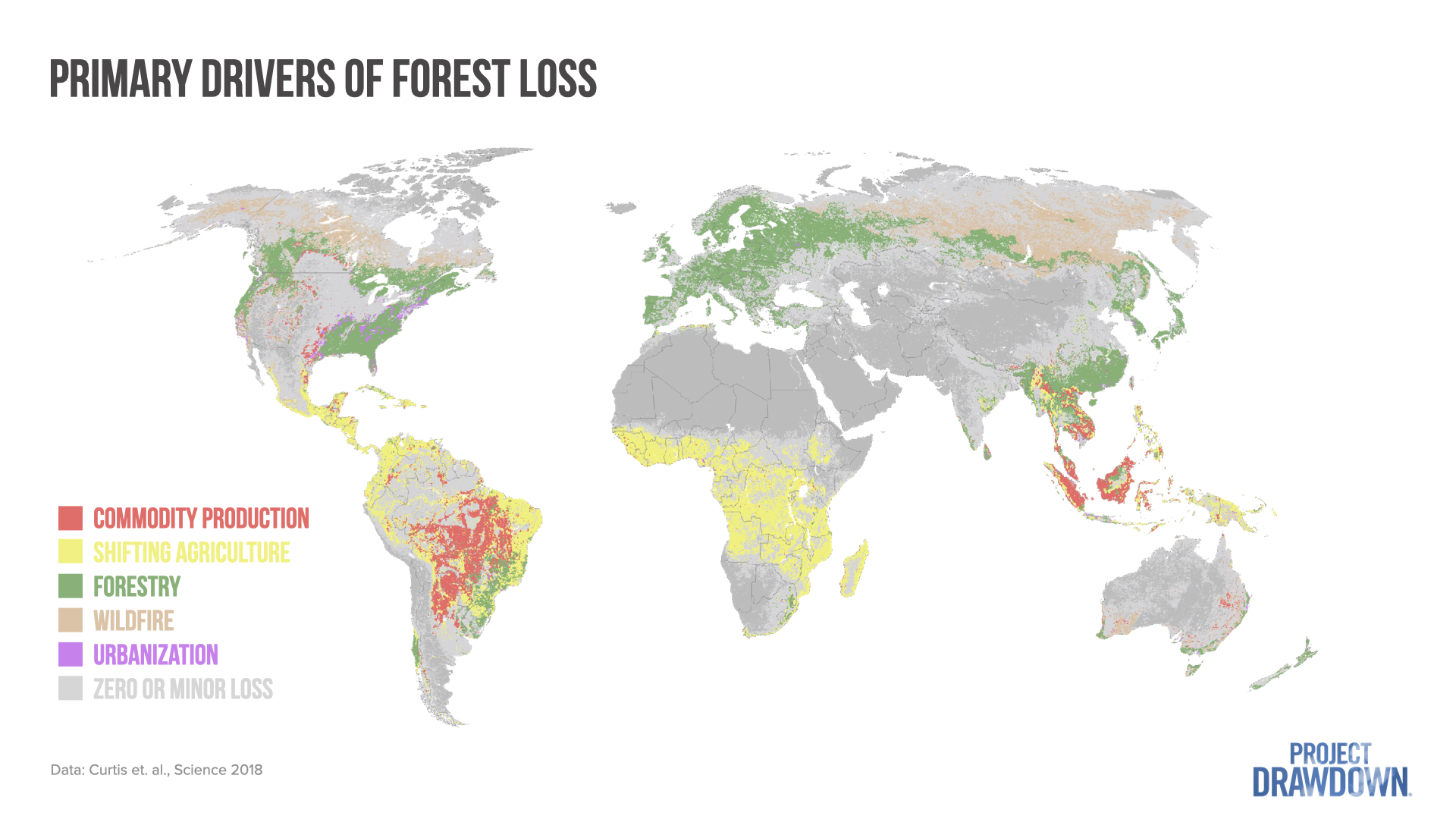

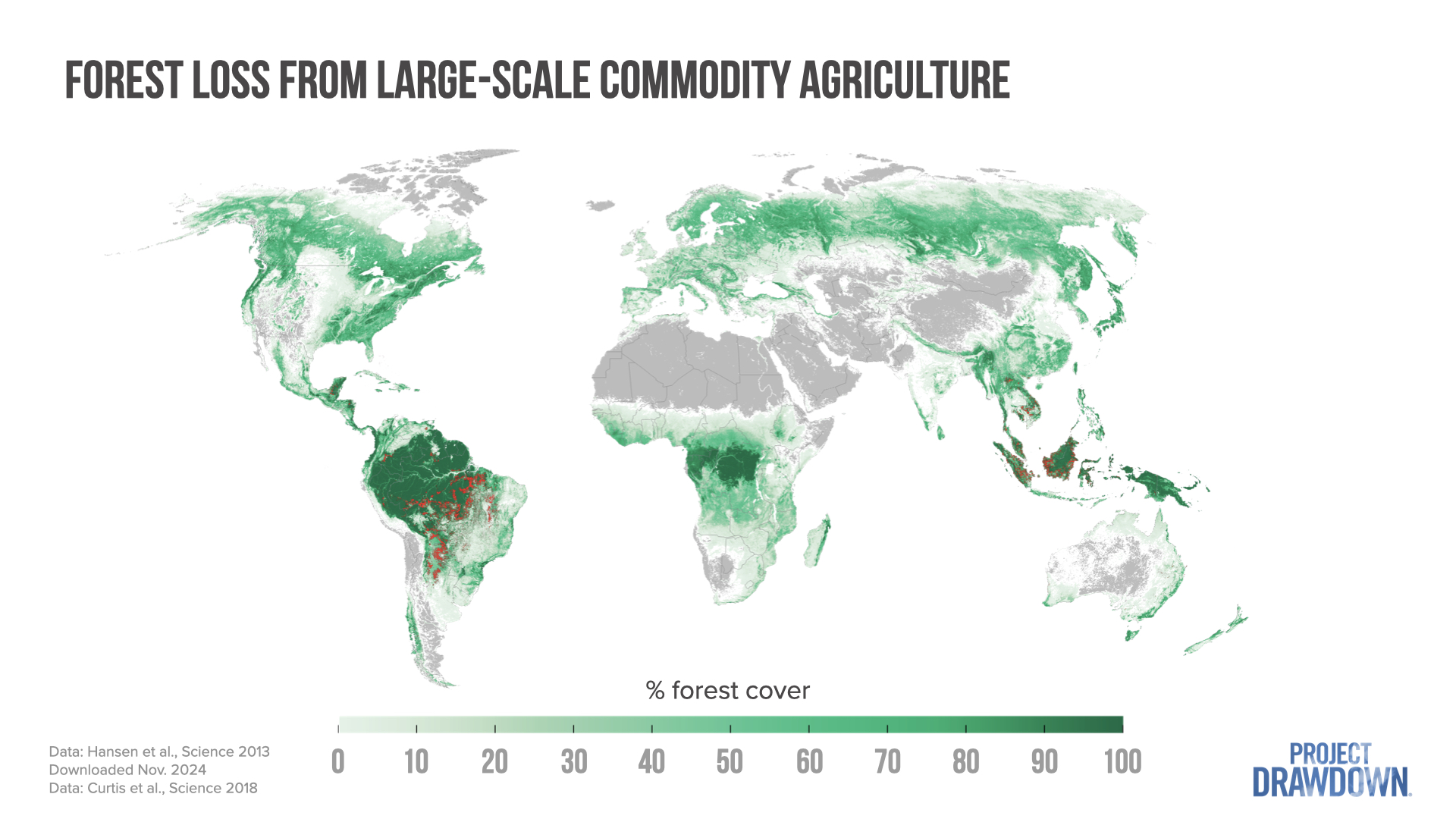

Today, the world’s forests cover about 4 billion hectares or roughly 30% of the Earth’s land surface. But forests are being cleared in many areas – for expanding agricultural land, harvesting timber and other forest products, mining, or urban sprawl.

Naturally, the loss of forest cover has enormous consequences for the environment. First and foremost, deforestation is a major driver of biodiversity loss, resulting in the decline of countless species and ecosystem health. Moreover, forests play a key role in regulating temperature, rainfall, and flow of water; their loss can lead to increased heat, runoff, flooding, and soil erosion in many parts of the world, degrading watersheds and aquatic ecosystems and putting agriculture at risk.

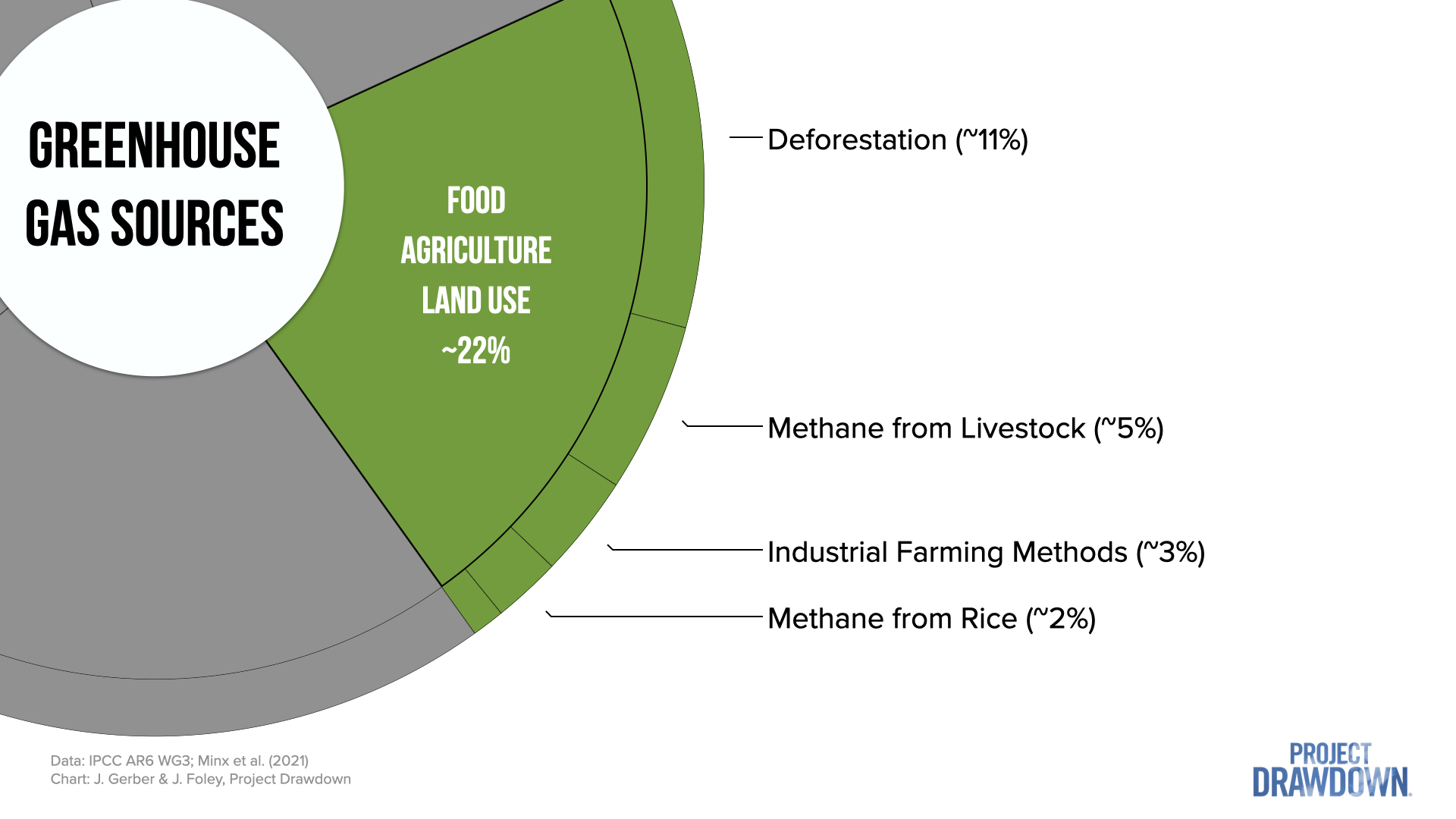

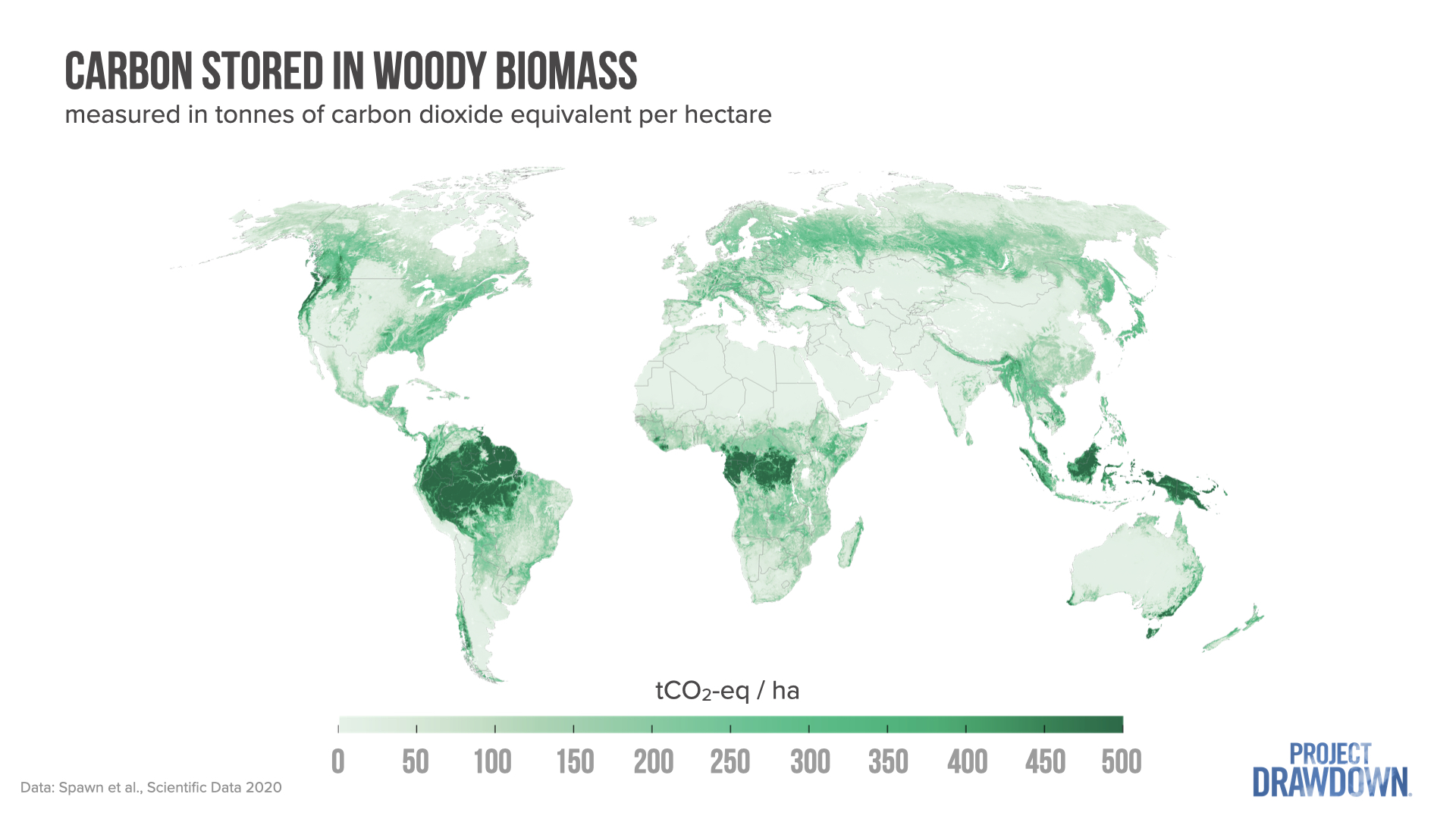

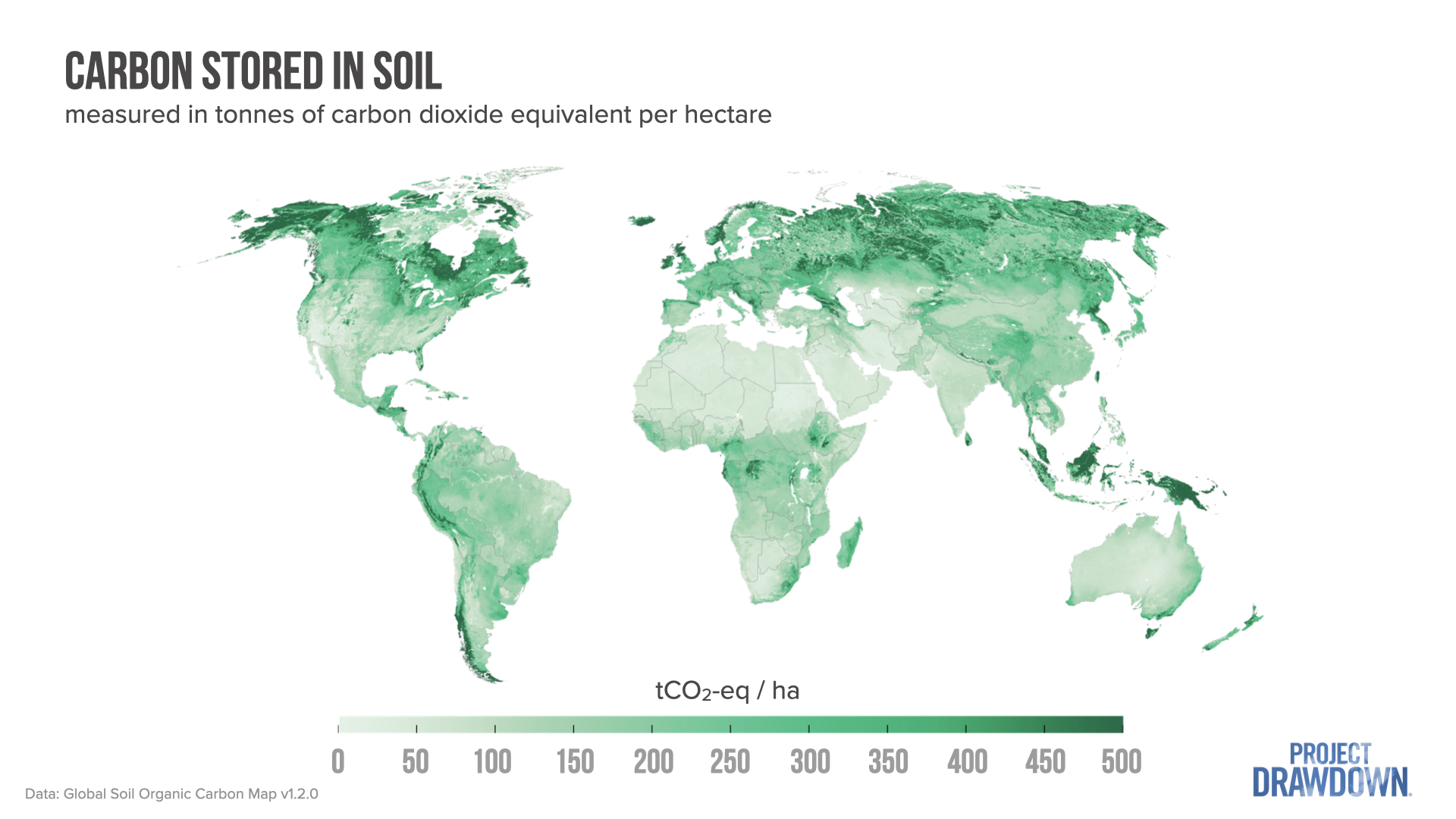

Deforestation is also a key driver of climate change. Clearing forests releases tremendous amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, mainly from clearing trees (and their woody biomass) and disturbing carbon stored in the forest soil. Not to mention the loss of future carbon removal as standing forests continue to grow.