Abrupt changes in yield gaps due to changes in the trajectory of the ceiling or the actual yield, however, can signal that something needs to change.

For example, these graphs show yield of two European grain crops stalling out around 2000:

The global food system isn’t broken, yet it needs fixing.

Agriculture is vital: It produces food for all of us, provides employment for over a billion people, and is central to many developing economies. It also is under a LOT of pressure: In the years ahead, it will need to meet growing demand while minimizing its environmental footprint and coping with a changing climate. If we improve yields on current farmlands, we can meet these needs without more land clearing – a huge contributor to climate change – and even allow some land to return to a natural state.

Technological improvements, from improved farming machinery, to readily available fertilizers, to the hybrid seeds of the Green Revolution, to computer-assisted modern farming technology, have dramatically increased productivity in the past. But how much more can yields be improved? And where?

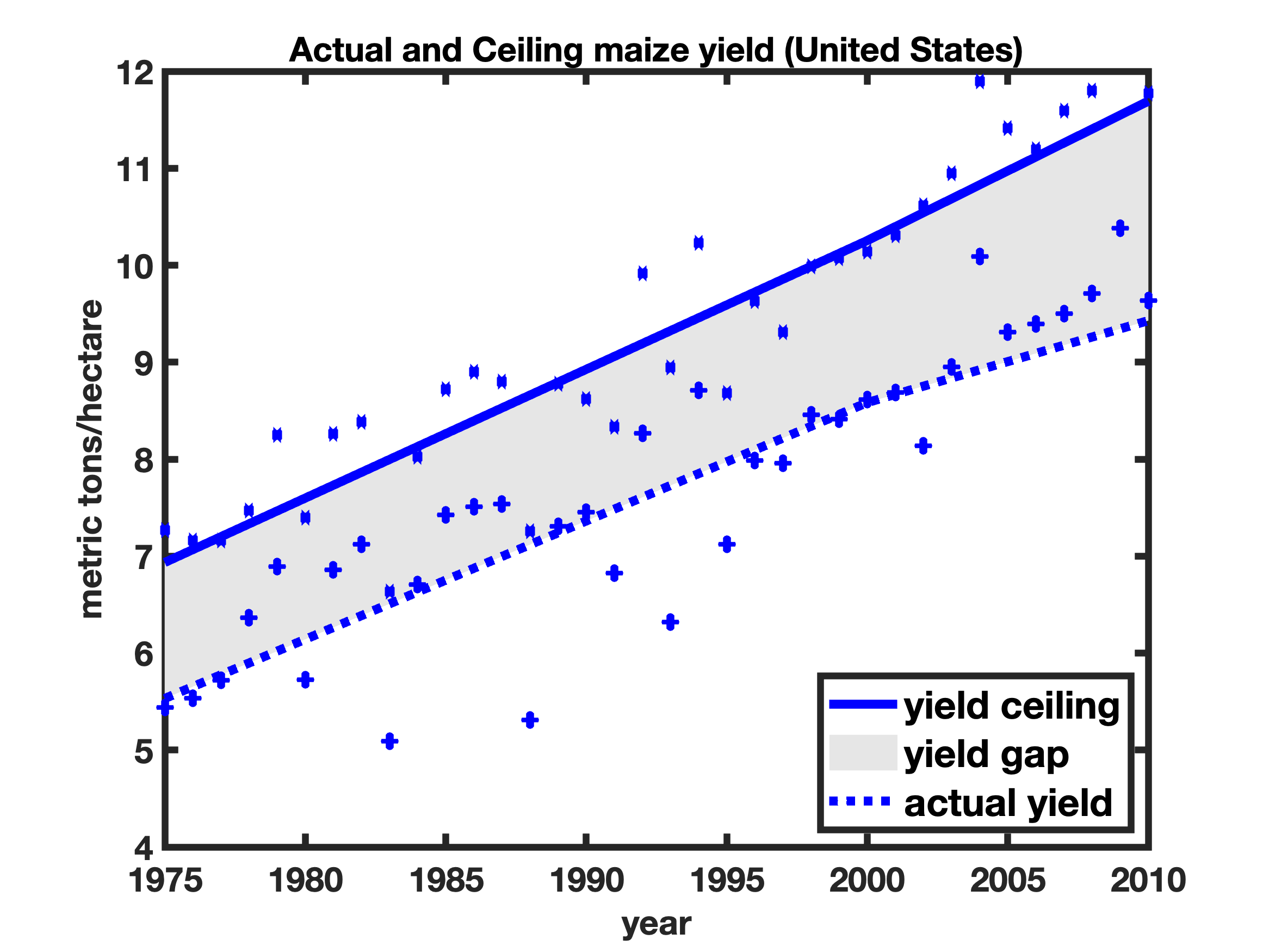

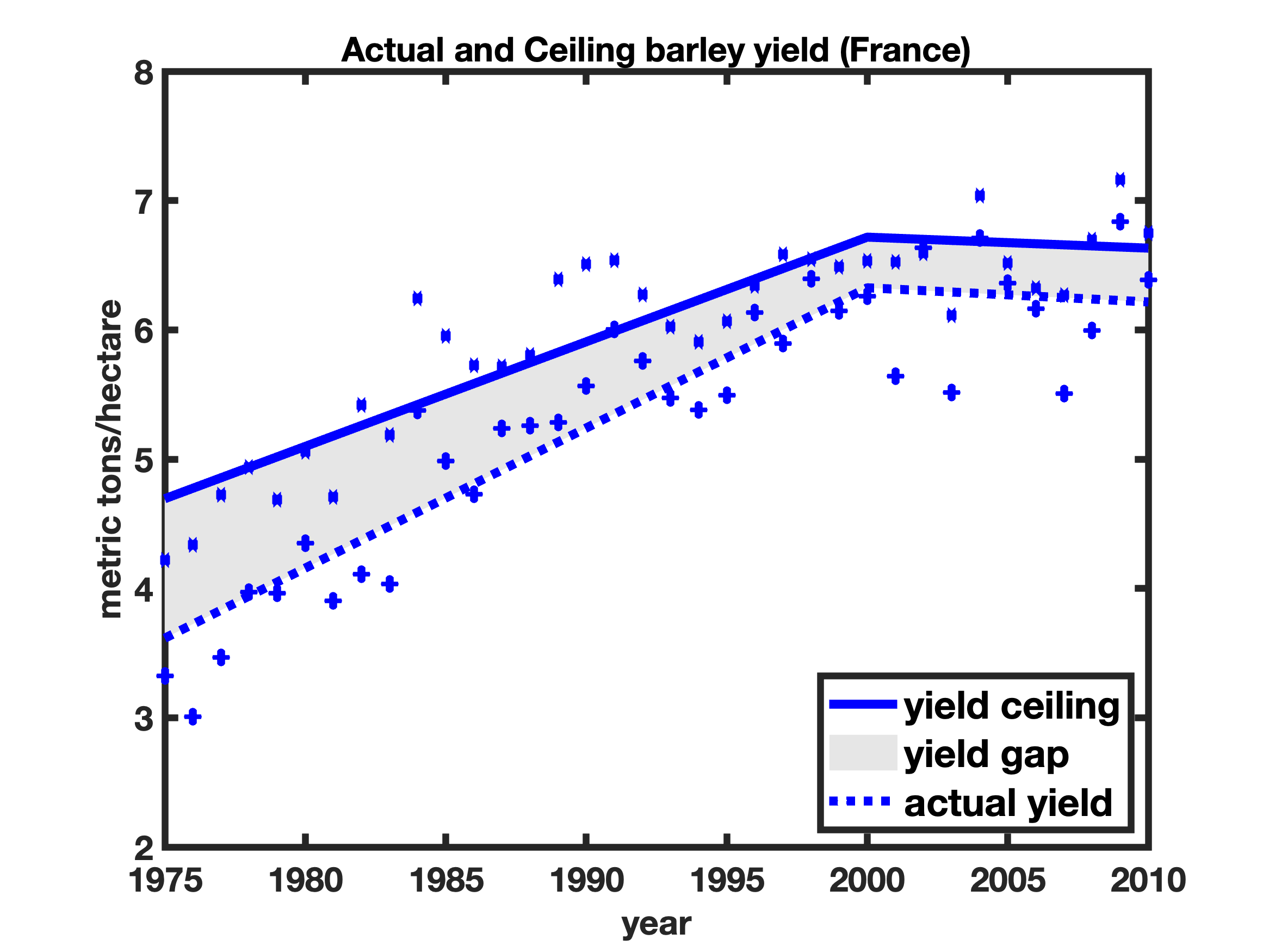

A study my colleagues and I recently published in the journal Nature Food examines this question through the lens of the “yield gap.” The yield gap is the difference between the per-acre or per-hectare crop yield farmers *could* obtain (the “yield ceiling”) and what they *do* obtain (the “actual yield”). Yield gaps aren’t necessarily a bad thing if it means that improvements are coming faster than farmers can apply them.

Take maize in the United States, for example. The yield ceiling has seen steady increase, thanks to research into improved cultivars, inputs, and farming technologies. The actual yield is steadily increasing as well, showing that farmers are adopting new technologies and practices at about the same rate they’re being developed, though with a bit of a lag.

Abrupt changes in yield gaps due to changes in the trajectory of the ceiling or the actual yield, however, can signal that something needs to change.

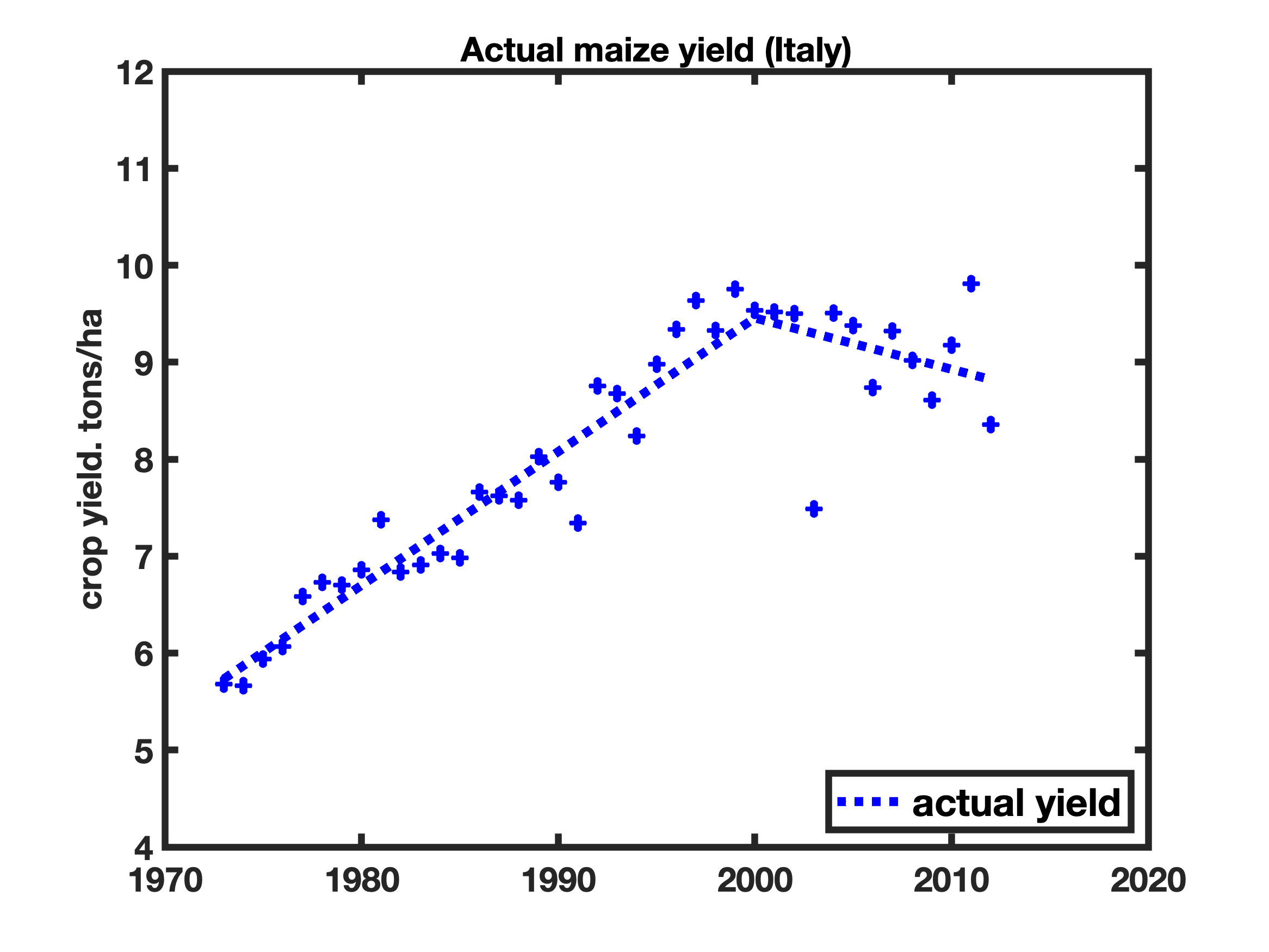

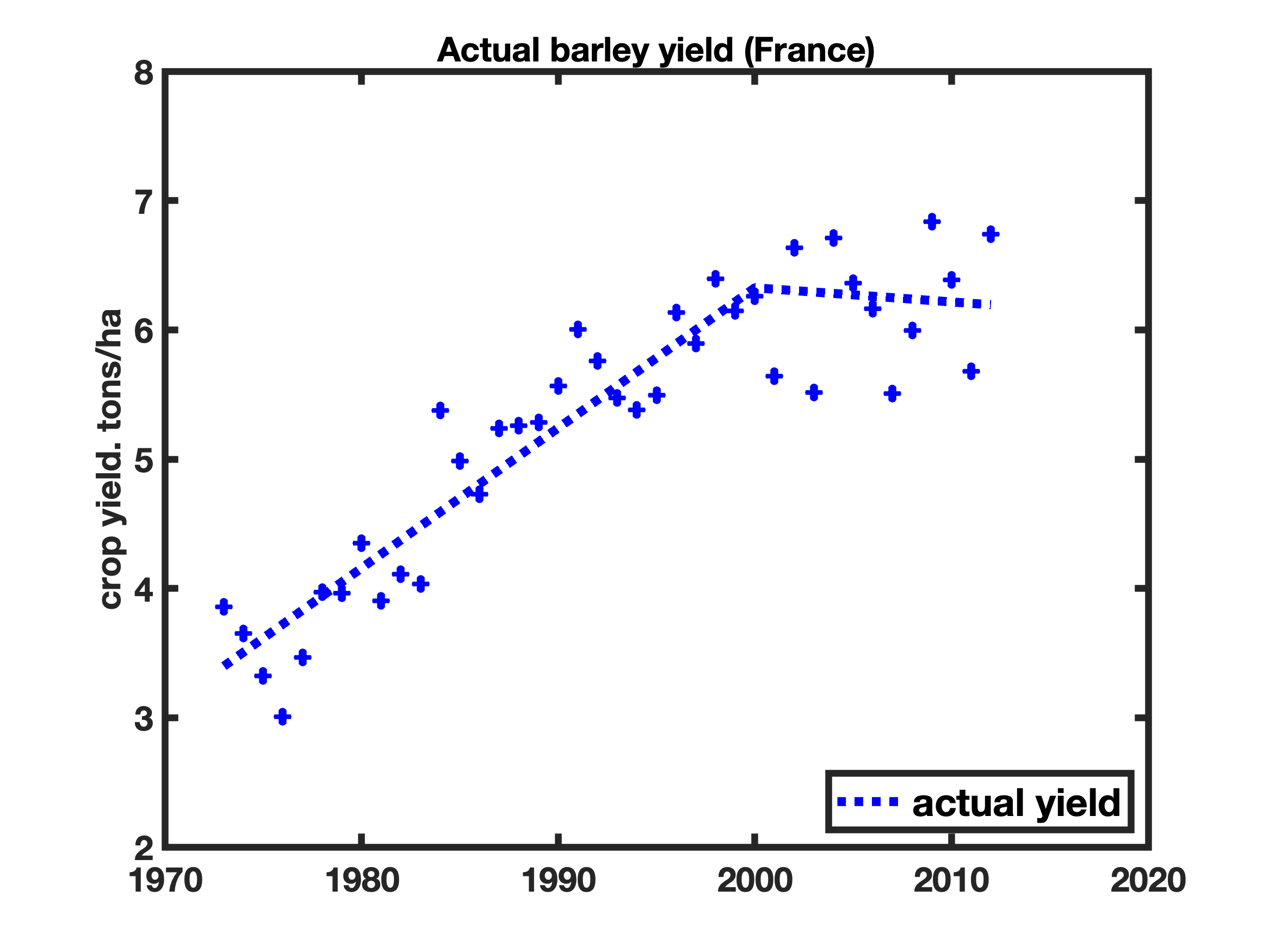

For example, these graphs show yield of two European grain crops stalling out around 2000:

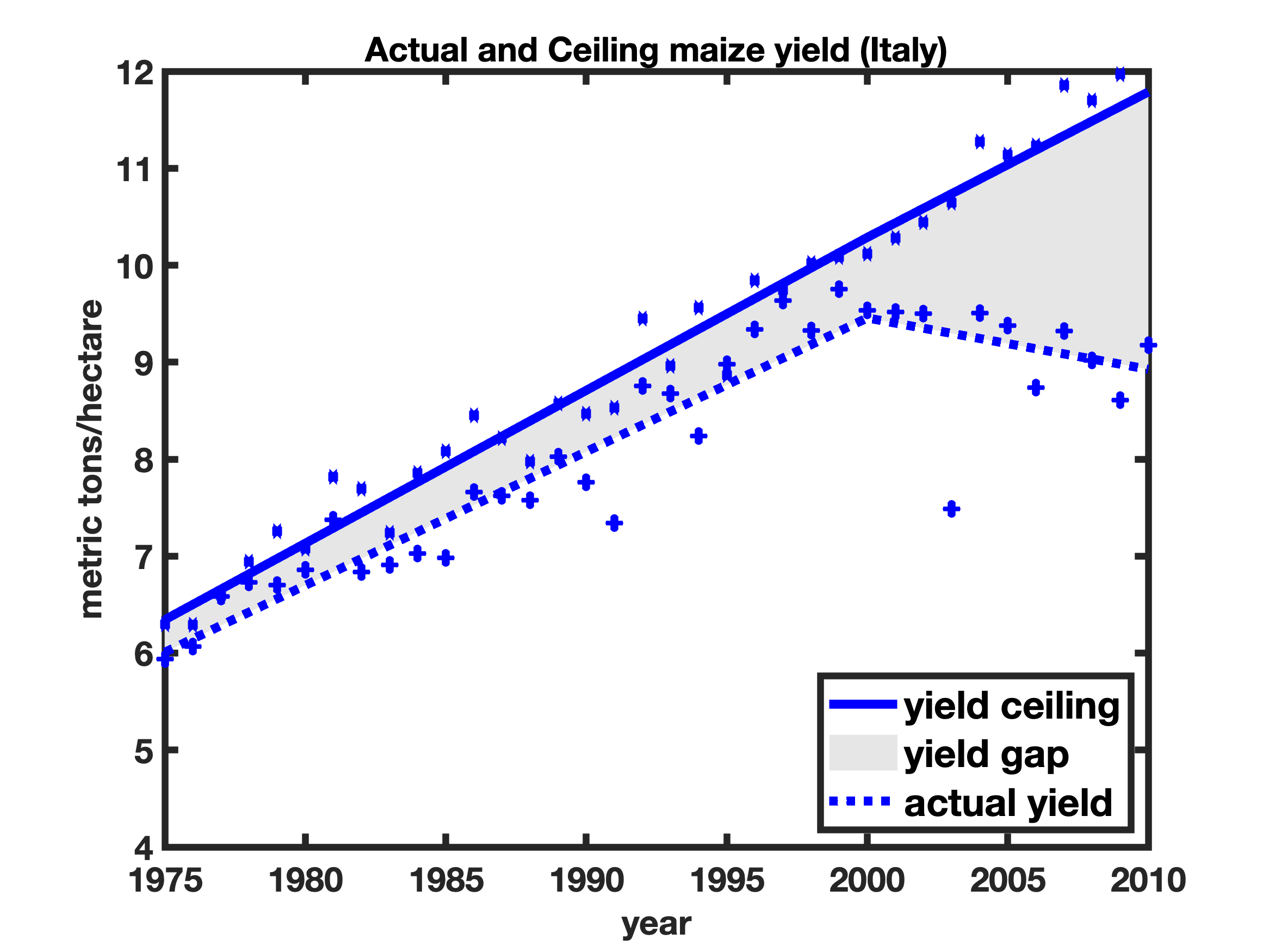

From these graphs alone, the two seem similar. But when we add the yield ceilings, it’s evident that their situations are very different:

In Italy, maize yields have dropped due to the European corn borer, so the gap increased as the yield ceiling grew due to the development of GMOs that resist the insect (and that aren’t allowed in Italy). In France, by contrast, both the actual yield and the ceiling stalled for barley, suggesting a need for investment in new technologies.

In our paper we identify three types of yield gap trends: “Stalled Floor” (like maize in Italy) “Ceiling Pressure” (like barley in France) and “Steady Growth” (like maize in the U.S.). Each suggests a different policy intervention needed to improve crop yields. Stalled Floor indicates that technology to improve yield exists, but farmers are not applying it. Here, philanthropists, NGOs, and businesses may wish to focus on supplying seeds or credit or education to farmers, or changing legislation. Ceiling Pressure situations, on the other hand, call for investment in improving agricultural technologies. Steady Growth indicates a healthy balance between investment in agricultural technologies and diffusion of new techniques, along with appropriate support, to farmers.

We found that these archetypes are distributed very differently across different crops and regions (click to expand maps):

Rice and wheat (which feed people) are at risk for yield stagnation, whereas maize (which feeds cars and cows, but in most places is not destined for food) has plenty of room for yield growth. This reflects the unfortunate reality that food security has not always been a priority for crop improvement. A more optimistic interpretation, though, is that the type of agronomic investment that has driven maize yields is possible for rice and wheat.

What does this all mean? By identifying the various kinds of yield gaps and where they occur, we are providing information that can be used to target investments appropriately, improving agronomic technology when yield gaps are closing, or pressing for change in regulations or market support or extension services that could best help farmers achieve higher yields where they are falling behind. This will help improve the global agricultural system, in turn providing gains for climate, environment, food security and farmer livelihoods.