It is a continent of paradoxes: rich in renewable energy resources but plagued by energy poverty; endowed with critical minerals but facing capital flight; courted as a climate partner but chronically underfunded when it comes to implementing solutions. As the world races toward net-zero, the question is no longer whether Africa will transition, but rather what that transition will look like, who will pay for it, and how it can be made truly fair.

Let’s explore the financing landscape shaping Africa’s energy transition by examining how things currently work, where they fall short, the actors involved, the structural barriers that persist, and the systemic changes needed to unlock a just and development-focused energy future. Understanding these interwoven dimensions can help in imagining a financing framework that supports Africa’s climate goals without sacrificing its development ambitions.

A tale of two realities

Today, Africa exists in a separate climate reality from that of the Global North. High-income countries are phasing out coal plants, banning internal combustion engines, and building out renewables at record speeds. Meanwhile, about 600 million Africans still live without access to electricity, and nearly 1 billion rely on wood, charcoal, and other forms of traditional biomass for cooking and heating. Indoor air pollution from traditional stoves causes over 600,000 premature deaths annually across the continent.

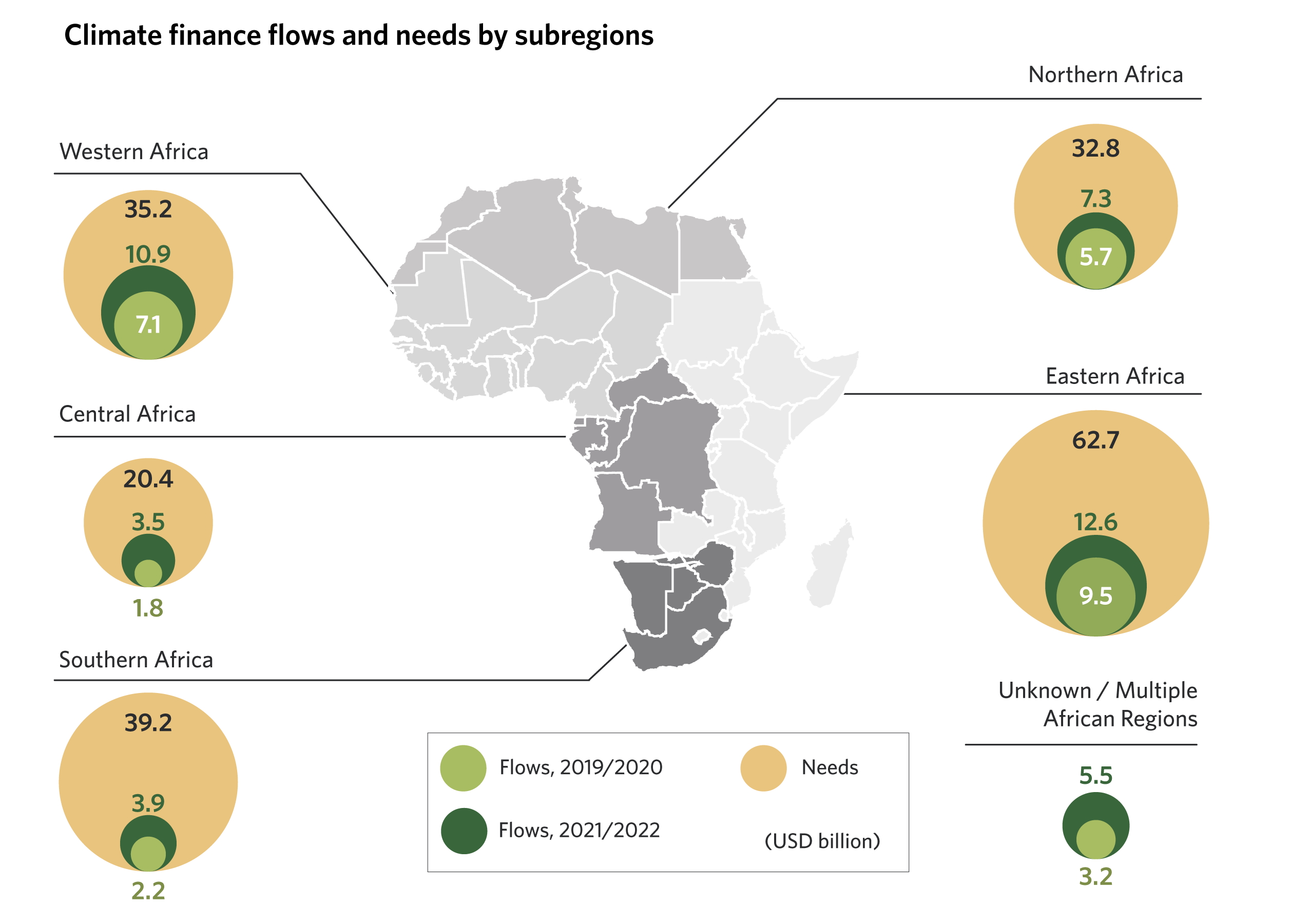

Africa’s energy transition is therefore about more than decarbonization. It is about escaping a developmental deadlock. It is about powering homes, hospitals, schools, farms, and industries. Yet the continent faces an uphill climb to achieve these goals while adhering to global expectations of carbon neutrality by mid-century. Meeting Africa’s energy and climate objectives will require more than doubling current energy investments of US$90 billion by 2030, with nearly two-thirds directed toward clean energy.

The problem with the current financing paradigm

The climate finance currently flowing to Africa is neither adequate, accessible, nor appropriate. Globally, Africa receives just about 2% of total climate finance, highlighting a significant gap in funding relative to other regions. Moreover, most of this funding is in the form of loans, not grants, further burdening countries already facing debt distress. Many multilateral development banks (MDBs) and climate funds prioritize risk-averse, commercially viable projects. This often means favoring large-scale solar and wind farms in politically stable African countries, while ignoring the urgent need to finance rural electrification and productive energy use projects in fragile African states.