These adverse health and climate impacts translate into large economic losses. In China, it is estimated that the economic toll from short-term exposure to black carbon in 2017 was more than US$7.5 billion. The impact of long-term exposure was even starker, resulting in financial losses of over US$53 billion.

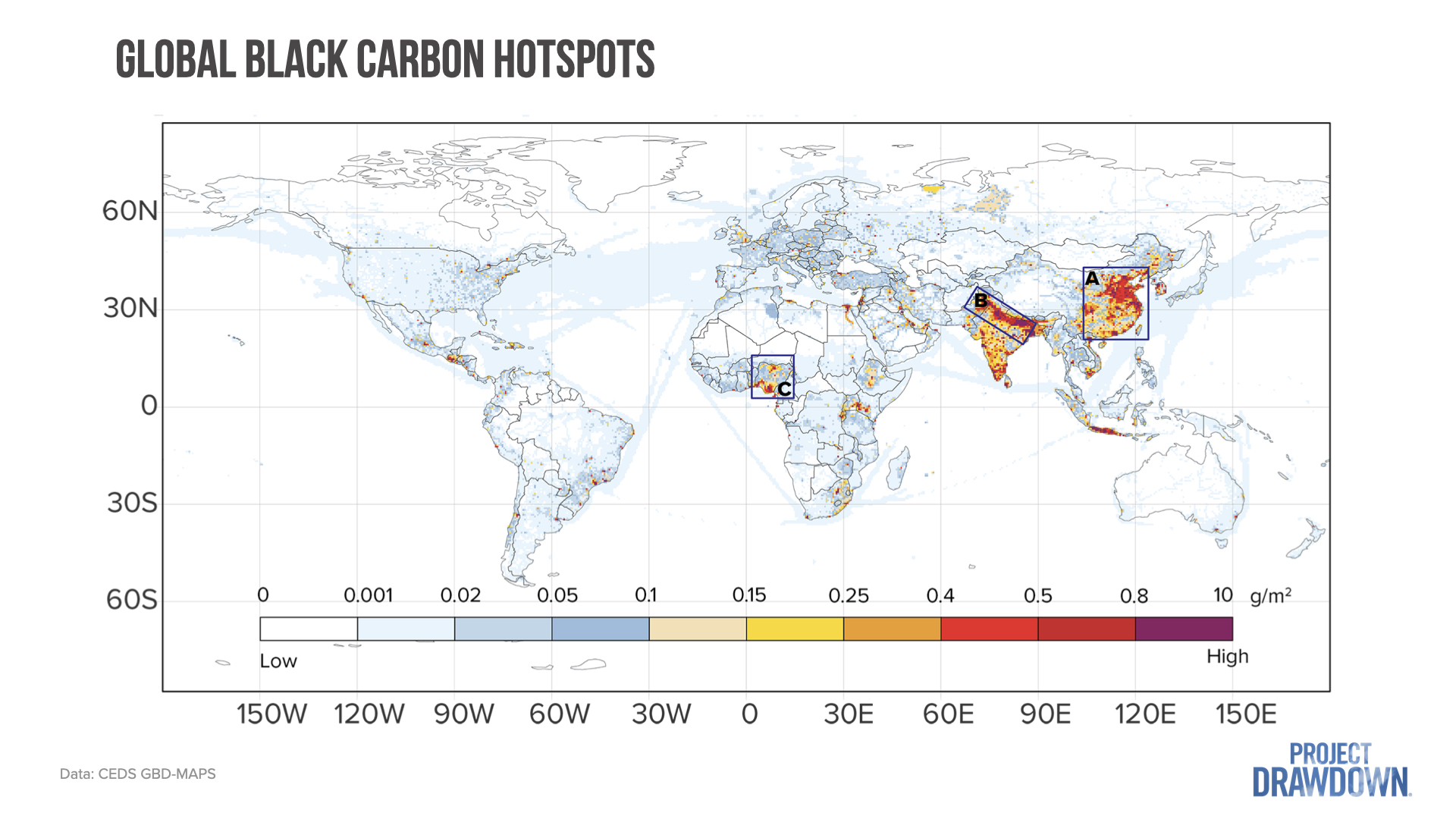

Although these impacts are felt around the world, the socio-economic (health, water security, economic opportunity) effects are felt most acutely at the local or regional level. Therefore, even world leaders who forget that instability anywhere is a threat to stability everywhere should feel compelled to act out of local self-interest.

A win-win-win for people and the planet

Reducing black carbon is a triple win, promising immense climate, health, and socio-economic benefits.

For the climate, it will lead to a short-term reduction in global warming, the protection of Arctic and Himalayan glaciers, and the stabilization of rainfall patterns.

For human health, it will save millions of lives. In my home country of India alone, reducing black carbon could save more than 400,000 lives each year by improving air quality. In Sub-Saharan Africa, reductions could avoid nearly half a million premature deaths annually.

Finally, for local socio-economic systems, it will have ancillary benefits such as increasing gender equality, reducing deforestation, and providing jobs and income opportunities. For example, women in low- and middle-income countries often spend many hours each week collecting wood for cooking. Access to clean fuel would dramatically reduce time spent collecting and cooking, and that time could then be used for recreational or economic activities. The World Bank found that the dependence on unclean cooking fuels leads to worldwide losses in women’s productivity of US$800 billion annually. In East Africa, where the demand for woodfuel contributes to rapid deforestation, clean cooking protects forests and the biodiversity they harbor.

A readily solvable problem

Given the myriad detrimental impacts of black carbon, you would think curtailing its emissions would be at the forefront of governmental agendas worldwide. Yet, disappointingly, efforts to reduce black carbon are severely lacking.

Only 12 countries set reduction targets for black carbon during the first round of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), each country's self-defined climate action plans under the Paris Agreement.

While advanced economies like the US, China, and the European Union have made commendable progress in reducing black carbon pollution, this headway is threatened by increasingly severe wildfires and, globally, is eclipsed by the rising emissions in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Based on existing policies, black carbon is set to skyrocket. For instance, transportation-related black carbon emissions in Africa could double between now and 2040.