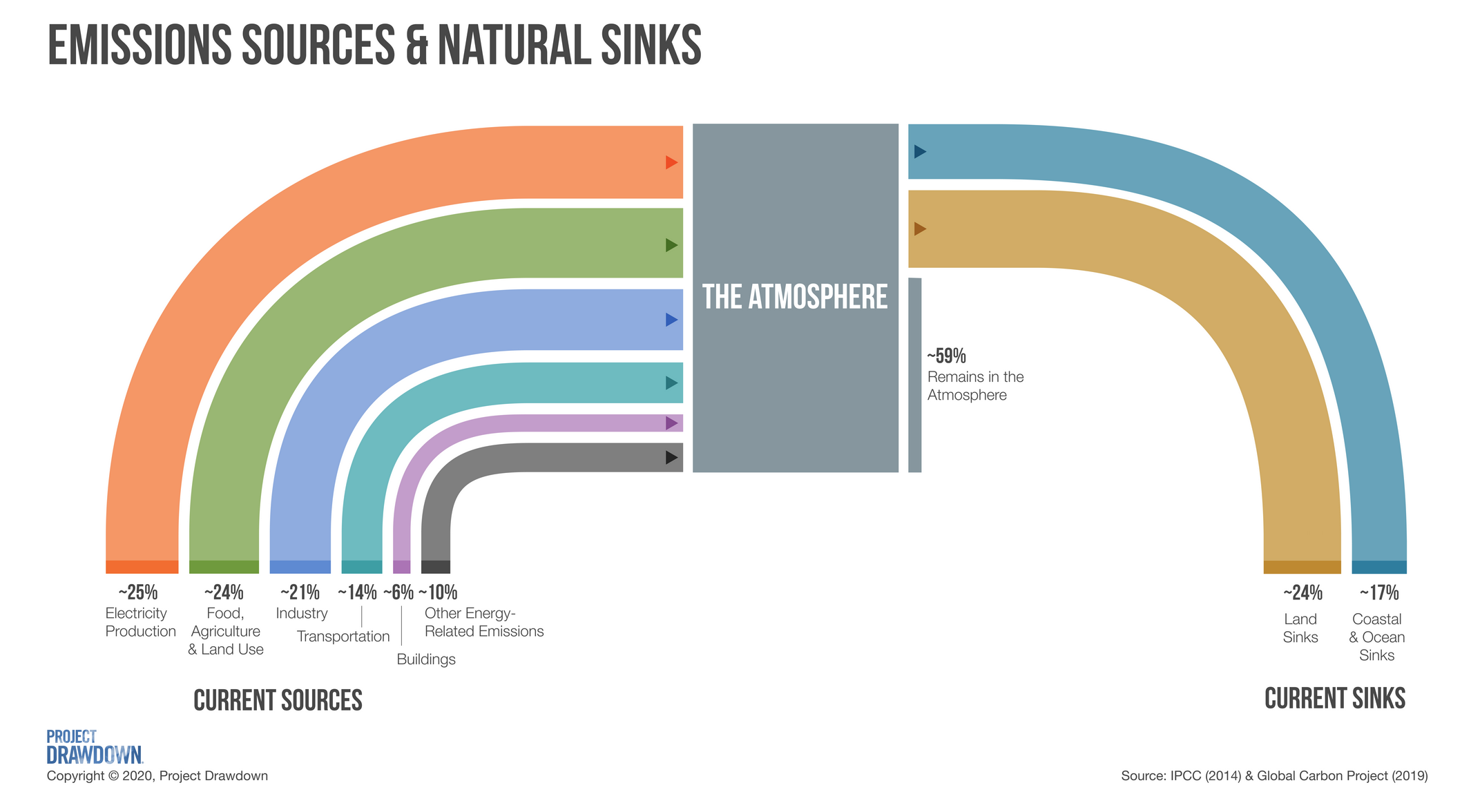

On this graphic we see greenhouse gas emissions on the left, divided into six big sectors that contribute to the problem. On the right, we see that our lands—from forests to prairies—and oceans are “sinks,” removing carbon dioxide (the primary greenhouse gas produced by human activities). Unfortunately, these sinks remove less than half of what we emit, and may not be able to keep it up as our emissions pile up in the atmosphere.

On the left hand side of the rainbow, we see that buildings account for about 6 percent of greenhouse gas emissions. Global emissions get assigned to sectors based on where those gases enter the atmosphere. For buildings, that means we’re counting only direct emissions that happen when a greenhouse gas is released at a building site. Those emissions predominantly come from burning fossil fuels to heat things up inside, such as air, water, and food. Not burning fossil fuels inside or next to our buildings is the best place to start in reducing buildings’ contribution to climate change.

But buildings have a much larger role to play in our journey to global net zero. Decisions we make about buildings will increase or reduce emissions in every one of these sectors.

- About half of the electricity we generate goes to buildings.

- Buildings are where we purchase and prepare food and collect our food waste.

- Many highly emitting industrial processes occur because we’re making materials that go into buildings.

- Transporting people usually means getting them from one building to another, and transportation options depend on the infrastructure we’ve built.

- “Other energy-related emissions” captures emissions linked to fossil fuels before they even get to our buildings, such as methane being released in the oil and gas industry.

So buildings are a critical piece of the puzzle if we’re going to reach global net zero. Should we advocate for making every building “do its part” by becoming net zero on its own?

While definitions vary, a net zero energy building will be energy-efficient and will produce renewable energy, preferably on site. The renewable energy produced, added up over a year, must be at least as much as the energy that the building uses over the same year. Zero energy buildings point our efforts toward energy efficiency and on-site use of renewable energy—a much-needed but limited set of the solutions available in the buildings and electricity sectors.

Similarly, a net zero carbon or net zero emissions building will balance the emissions it adds to the atmosphere with the emissions it removes from the atmosphere. That reflects our global net zero goal. Zero carbon buildings point our efforts toward material efficiency in design and non-polluting operations—critical advances that push us in the right direction.

So what’s the problem? There are several potential pitfalls. First, a net zero standard can create the temptation to “balance out” emissions with offsets. An emissions offset is supposed to incentivize someone else to cut emissions, but all too often this becomes a carbon shell game. We’re kidding ourselves if we believe that there’s always someone else to make the deep emissions cuts we need on a global scale.