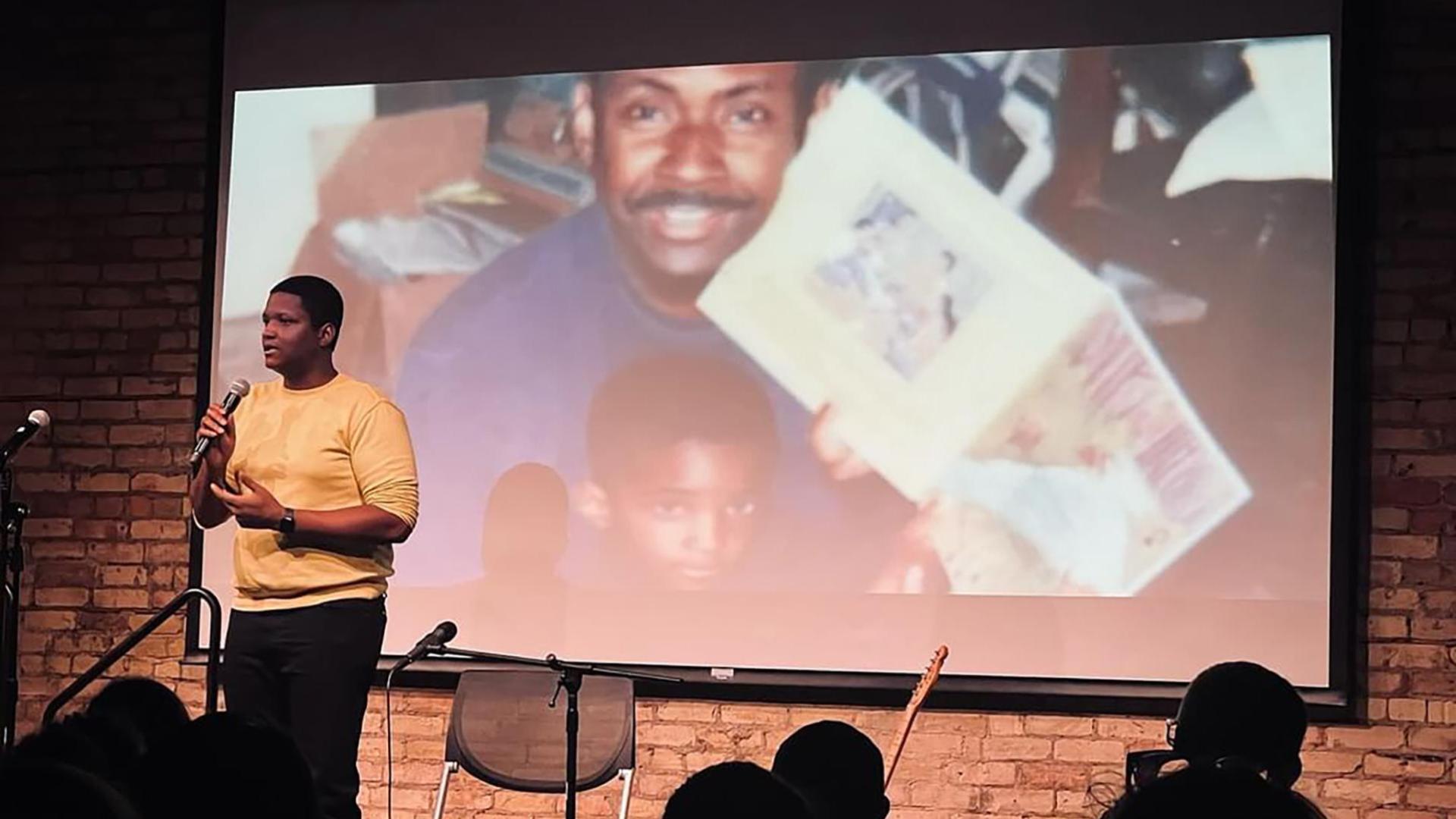

Over time, in reflecting on my dad’s example, I realized that I can withstand discomfort to use my role as a storyteller to lift up underrepresented voices, share their resilience and leadership, and celebrate their real-world superpowers.

One of the climate superheroes I’ve met through the stories I’ve shared is Clara Kitongo. Clara shares, "Sometimes, we don't know that we have a superpower… realizing, ‘Oh, because you're born in Uganda and you have this unique experience, that is in itself a superpower because of the perspective you bring to the table.’”

Clara’s journey from seeing her identity as a burden to recognizing it as powerful is an example of the influence that narrative can have. Clara is an engineer, educator, and musician from Kampala, Uganda. Many of the dreams she had as a child were not things her culture saw as “important.” While today she lives in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, promulgating equity and planting trees as a climate solution, she didn’t initially see such a path. She recalls being fearful when entering the climate space as a Black woman. Clara credits Kenyan environmental activist and Nobel Peace Prize winner Wangarī Maathai with helping her see her own power. Wangarī has been called “the troublemaker who fought back with trees” and received a master’s degree from the University of Pittsburgh; Wangarī paved the way for Clara as a young African woman working with trees in Pittsburgh. This is a tangible example of the power of representation in the stories we tell. Representation can and does drive belonging, and serves to build power, shape culture, and change behavior.

In sharing my dad’s story, Clara’s story, and the stories of underrepresented changemakers everywhere, I want people to see themselves and their power. All too often the messages we receive make it challenging to find our place. Therefore, stories that encourage us to tap into our agency are critical.

While discouraged when called names like “little Black boy,” my dad found empowerment through the stories he was told.

My dad told me, “I just gritted my teeth and said, ‘Wait and see.’ I studied harder. I studied longer. I memorized textbooks and it didn’t matter. Instead of lashing out, I said I will do better. … I had people, my grandmother and my mother, show me and tell me my value. … When we used to make speeches in church, I practiced with my grandmother, Rosetta Allen Brown. She said to me, ‘Mose, you can memorize a lot. You gon’ be something when you grow up.’ There was… that positive tone.”

Everyone has a more meaningful story than we may realize on the surface, but we often don’t know it’s there or appreciate its power.

There’s a saying that you can't be what you can’t see. Too often the mainstream narrative about underrepresented communities is one of victimhood, and it can be an arduous journey to discover our power. Positive representation in stories is critical for identity development and invites us to embrace our role as heroes.

My dad's story has inspired me to share stories that will bring about the end of the climate crisis. The same is true of Wangarī Maathai for Clara. Seeing people like us doing extraordinary things expands our idea of what's possible.

When it comes to the climate crisis, we need stories that help us recognize and leverage our power. This means representing the full diversity of solutions and problem-solvers, rather than perpetuating an exclusionary narrative. We need to pass the mic to the voices that often go unheard, and ask ourselves critical questions: Whose voices are being heard and whose aren't? What impact can those heroes and their voices have if we just listen? By questioning the status quo and passing the mic, each of us can help others discover their roles in solving climate change. We can discover that our power to do something about climate change is far greater than our wildest dreams.

Matt Scott leads Drawdown Stories at the climate solutions non-profit Project Drawdown. This essay was crafted with support from Jothsna Harris of Change Narrative LLC, which exists to build capacity in the climate justice movement through the power of our stories. For more on the Drawdown’s Neighborhood series, visit drawdown.org/neighborhood.