As with a household budget, it's never easy or comfortable to make cuts to our carbon budget, but some places are more straightforward to start than others. While no emissions are truly easy to abate, attention and investment often go toward sectors with effective, developed solutions, such as power generation and passenger transport. Yet addressing stubborn “hard-to-abate” emissions is essential for balancing the global greenhouse gas budget. Over the next few decades, we must invest in and diversify our strategies to tackle these hard-to-abate emissions. To do this, we need to understand what these emissions are, why they are critical to meeting our climate goals, and the diverse actions we can take now and in the future to meet this climate challenge.

What makes certain emissions hard to abate?

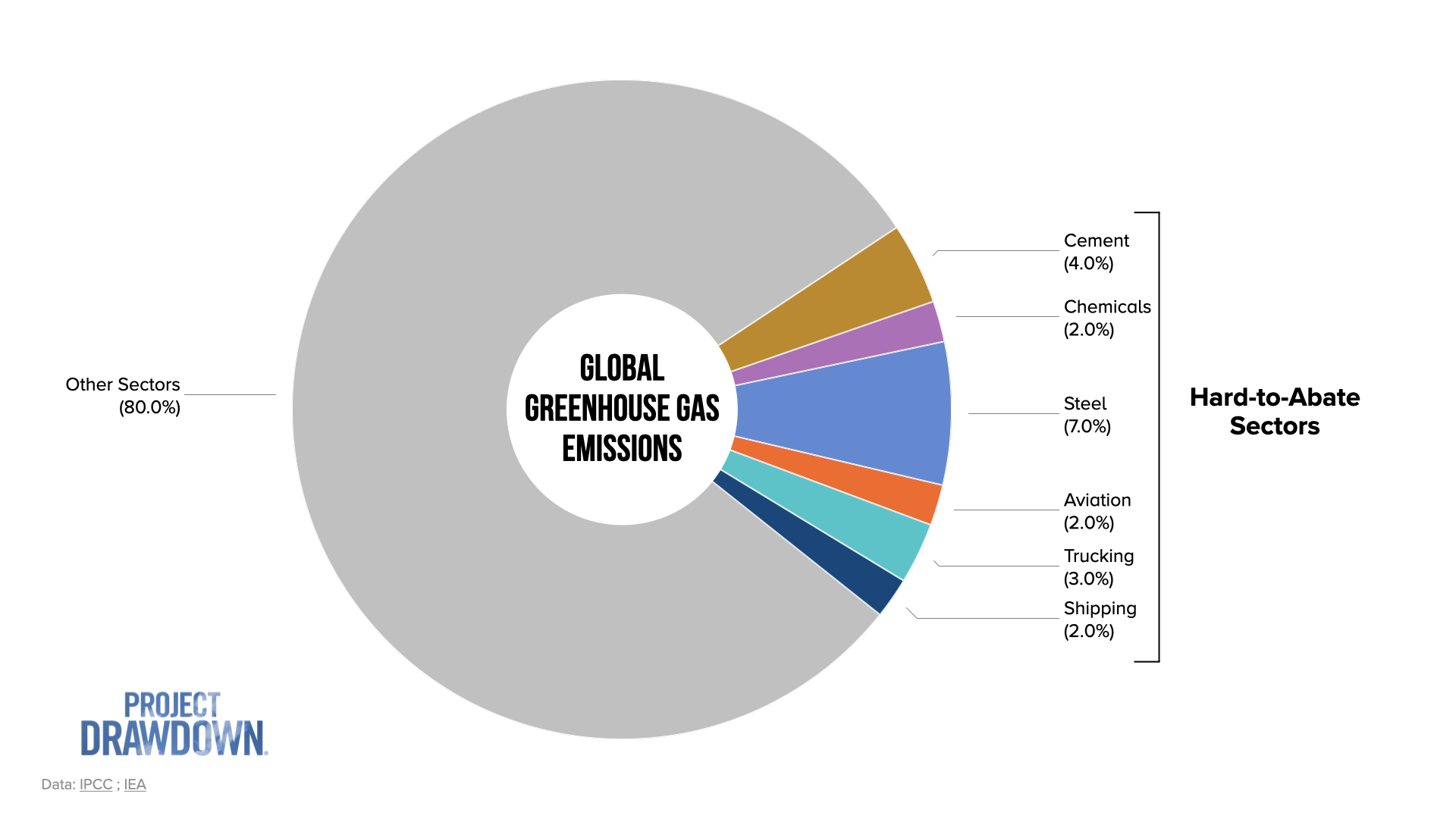

Emissions from several sectors are most commonly considered “hard-to-abate”: aviation, shipping, trucking, and heavy industry (producing materials like cement, steel, and chemicals). Hard-to-abate emissions are diverse in their challenges and sources, but they have a few things in common. First, hard-to-abate activities are caused by human activities rather than natural processes. They also operate on a huge scale: 4 billion metric tons of cement and 1.9 billion tons of raw steel were produced worldwide in 2024, and 62 trillion ton-miles (equivalent to shipping one ton over one mile) of global maritime trade were traveled in 2023. For context, all the mammals on Earth – all of the elephants, humans, blue whales, and countless other species – weigh around 1.1 billion metric tons.

Not all emissions from these sectors are difficult to prevent; we can avoid the release of a portion of the greenhouse gases with readily deployable solutions, including electrifying processes wherever possible, switching to lower-emission fuels, and improving efficiency. However, hard-to-abate sectors have large quantities of emissions that defy available solutions, known as residual emissions. It’s really these residual emissions that are hard to abate, and they stem from a few broad challenges:

They generate (currently) necessary process emissions

Process emissions are unavoidable using current manufacturing pathways. They come from chemical reactions during the production process itself, rather than emissions from fueling that process. One example is cement production; the raw materials used to produce cement contain carbon, and that carbon is released as CO₂

in cement kilns. Cement manufacturing is a hard-to-abate industry because the material composition or production process would need to fundamentally change to avoid these emissions.

They are energy-intensive

Often, hard-to-abate activities consume huge quantities of fossil fuels to produce energy. They require high energy inputs to run, while operating at scales and temperatures that make cleaner energy sources difficult to deploy in the near term. Producing steel, for example, requires heating iron ore or steel scrap to over 1000°C, a temperature that requires large amounts of coal, natural gas, or other fossil fuels to reach.

There are technological hurdles to energy transitions

Cleaner, renewable energy sources aren’t always available to reduce hard-to-abate emissions. For instance, moving aircraft and container ships requires fuels with high energy densities. We currently lack commercially available batteries or alternative fuels to move these sectors away from fossil fuel consumption. In contrast, batteries for electric passenger cars are being adopted around the world, offering an electrification solution for emissions that would not be considered hard-to-abate.

There are economic challenges to fast adoption

These activities often require expensive and long-lasting infrastructure, resulting in slow equipment turnover and replacement. This creates financial hurdles for companies or governments looking to adopt cleaner technologies. Also, small increases in manufacturing costs could be a deterrent if margins are low.

As daunting as these challenges may seem, they are not impossible hurdles. But developing and deploying solutions to these challenges at scale will take time. This makes it all the more important for other sectors to prioritize emergency brake solutions, rapidly reducing greenhouse gas emissions this decade, while technologies to address hard-to-abate emissions develop more slowly.

Why do we need to address hard-to-abate emissions anyway?

We know there are many proven solutions we can deploy today that have effective, immediate impacts on greenhouse gas levels in the atmosphere. So, you might be wondering, does it make sense to spend time and money on hard-to-abate emissions in the first place?

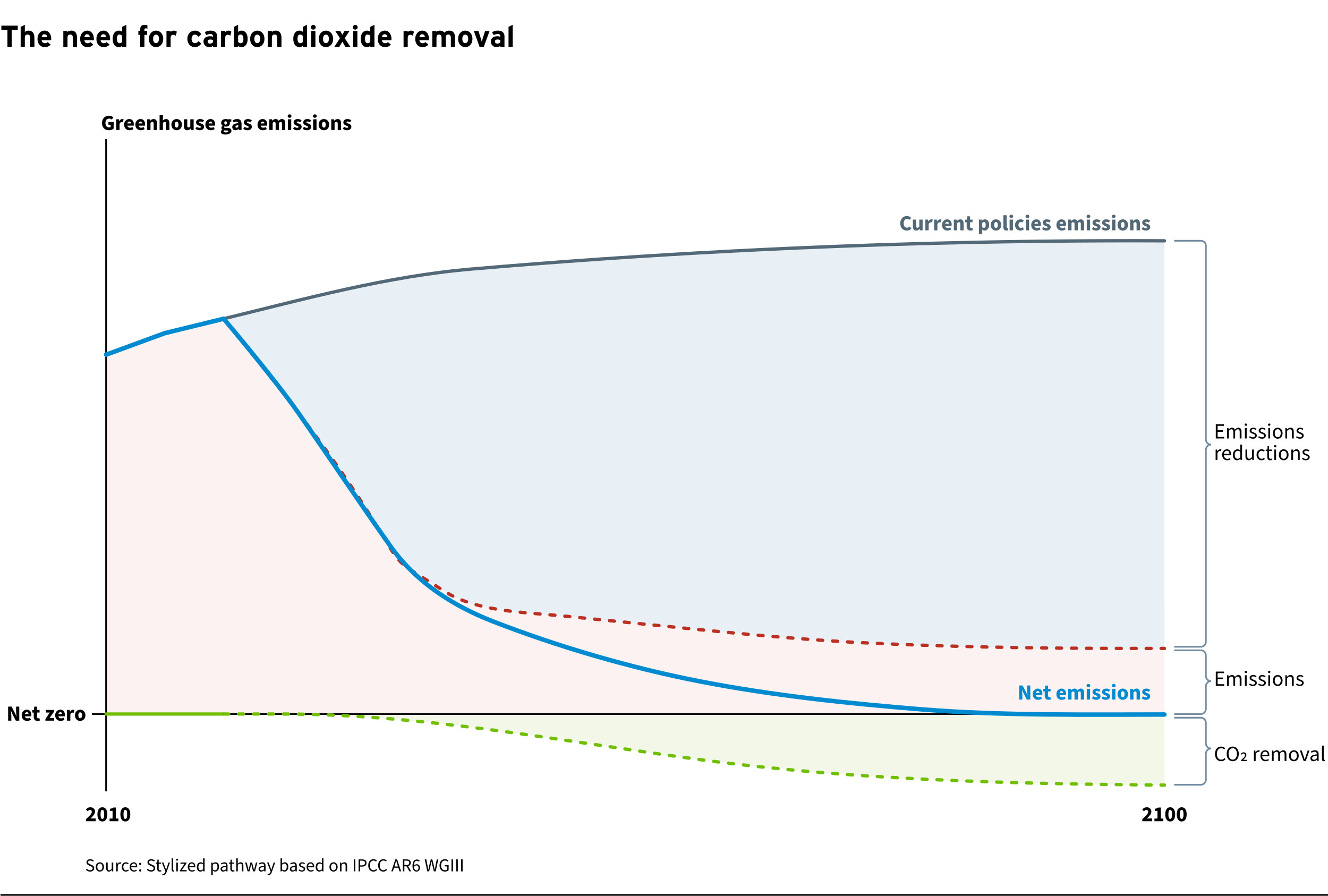

In short, yes. Balancing our global carbon budget will require ambitious actions across all sectors, and hitting that balance becomes tricky if hard-to-abate emissions remain high. In the International Energy Agency's Net Zero Roadmap, which outlines a global pathway toward limiting global warming, industry and transportation sectors are responsible for 90% of residual emissions by 2040.

We could achieve net zero without necessarily eliminating all residual emissions, thanks to carbon sinks that remove greenhouse gases from the atmosphere. However, it would be risky to rely on carbon removal alone to balance the budget. Natural sinks, such as forests, take time to grow, and technological sinks, such as carbon capture, are largely unproven or ineffective.