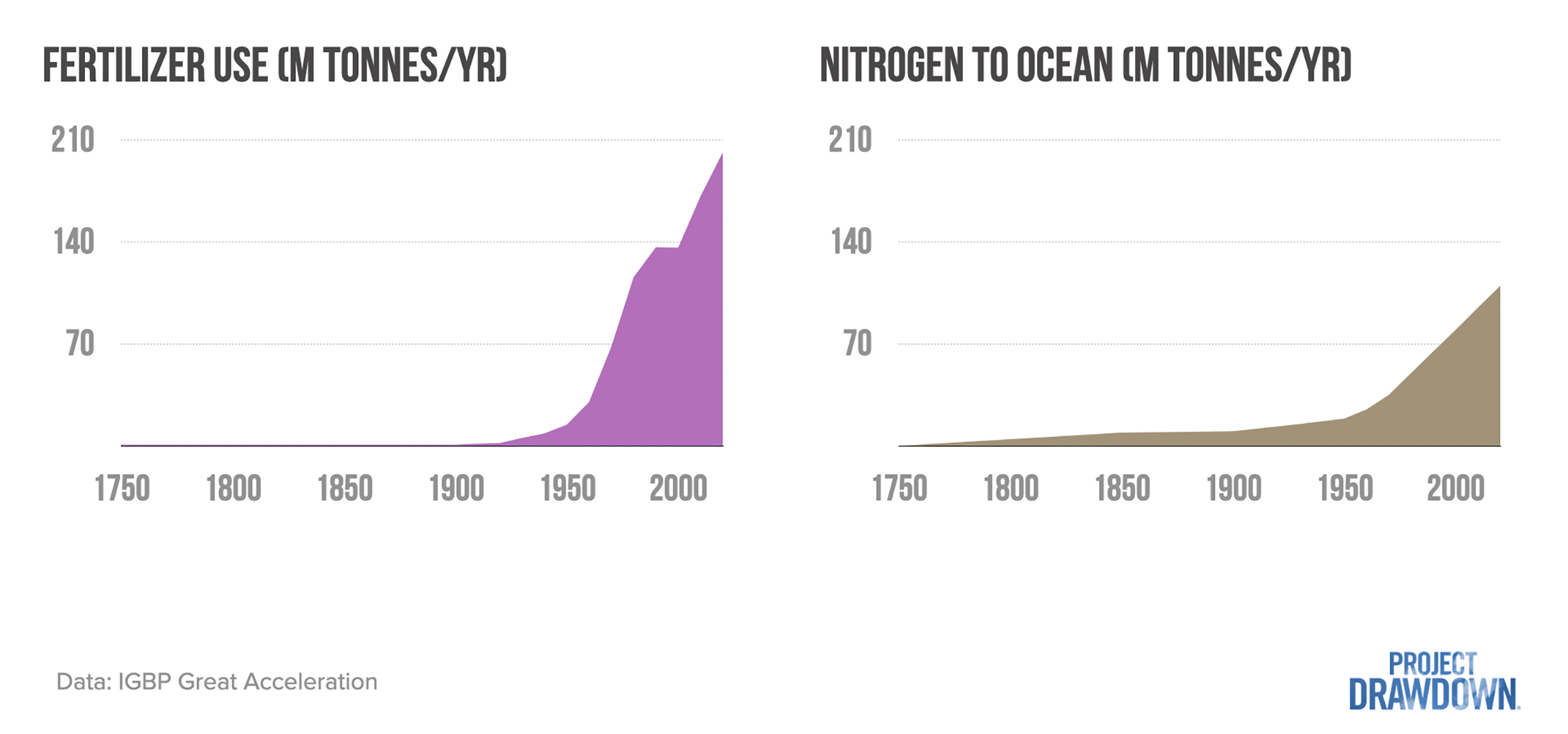

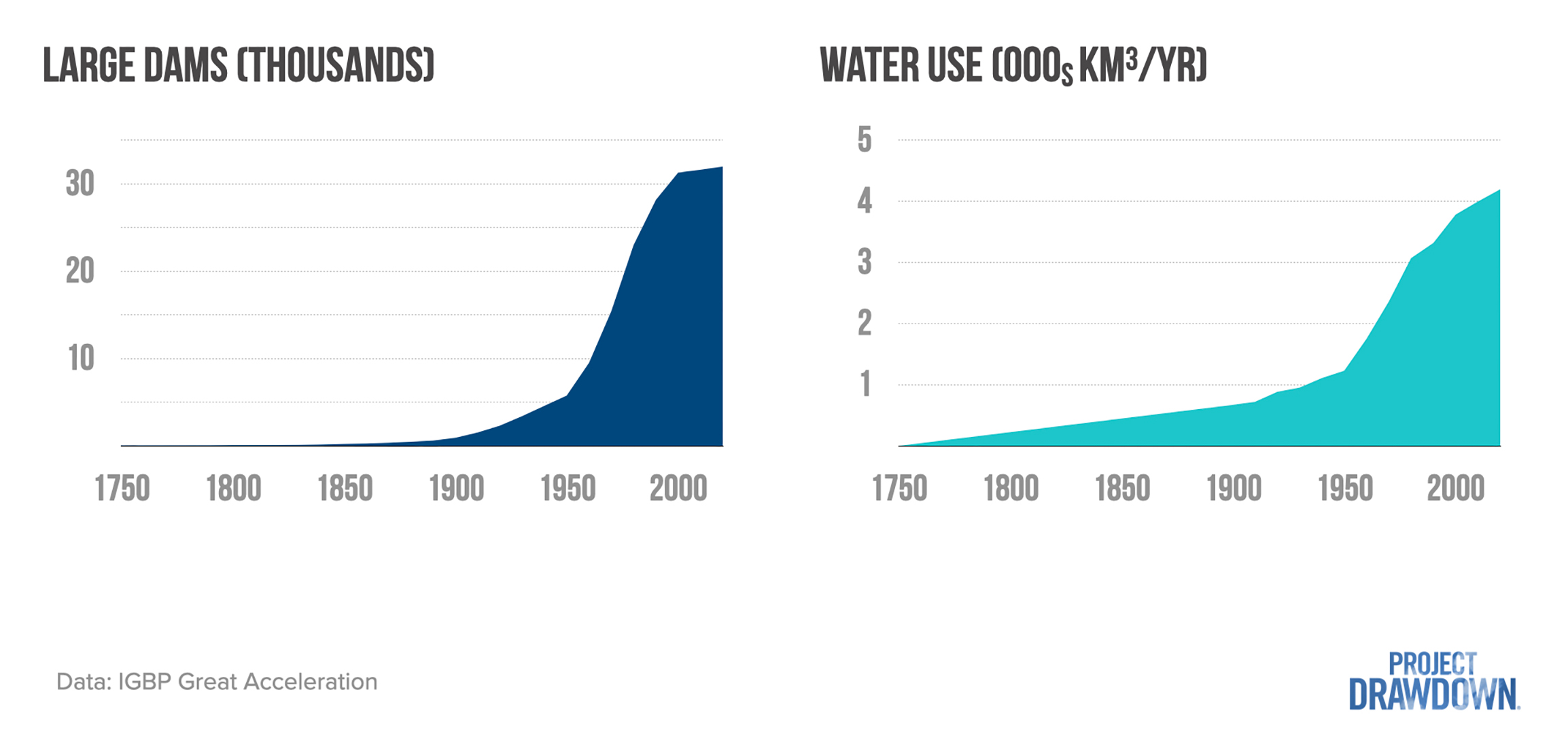

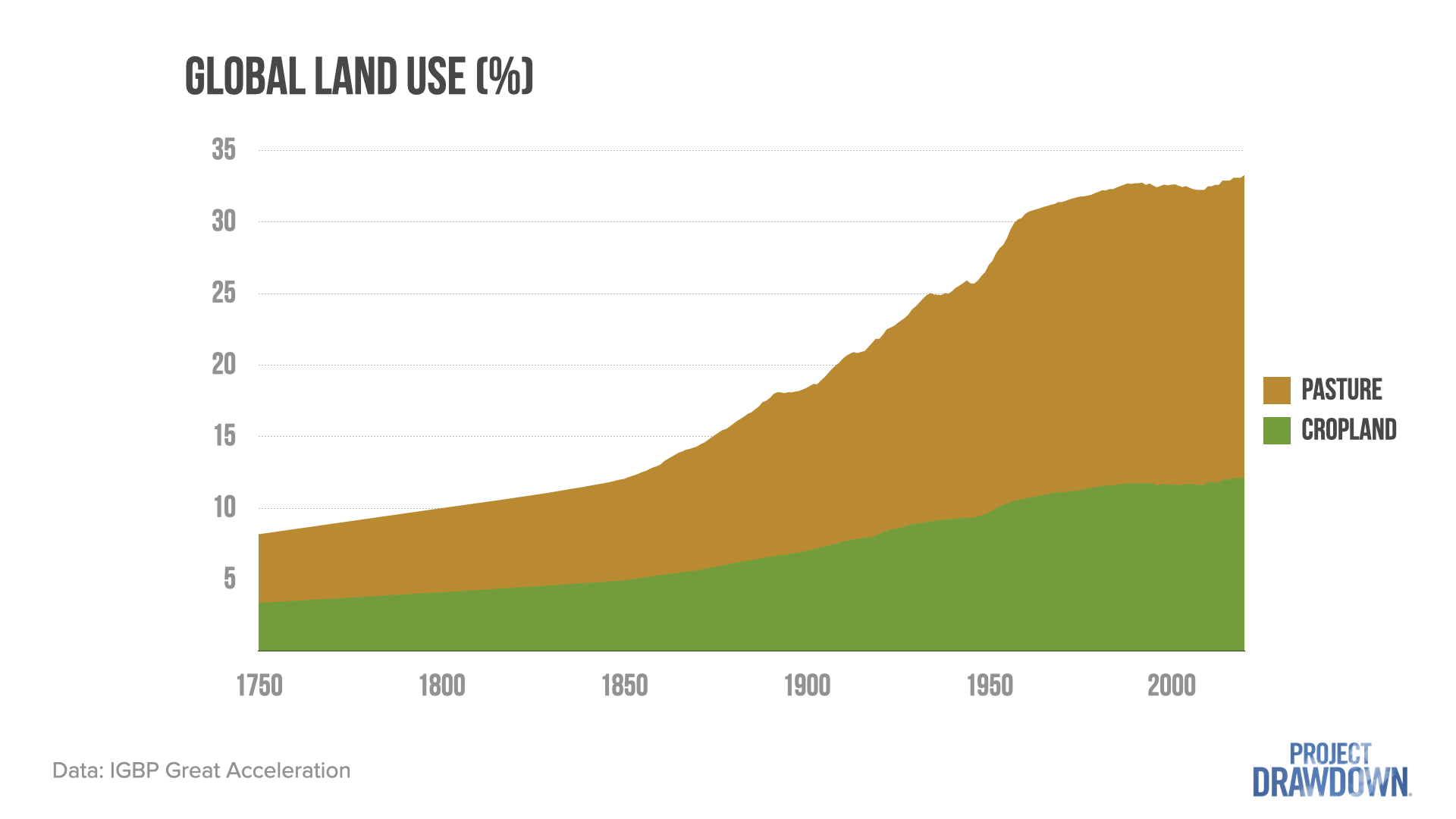

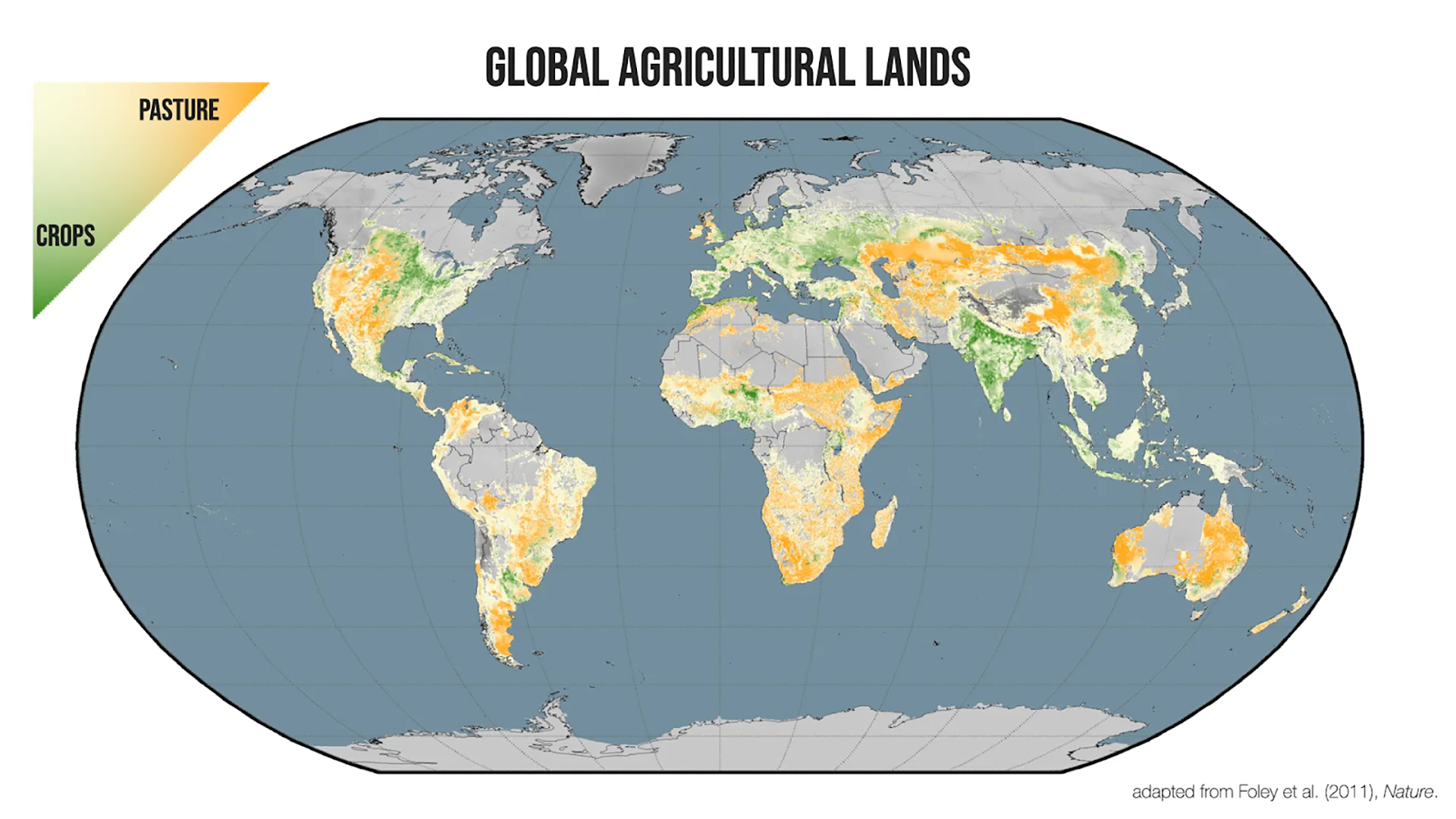

But starting in the 1960s, we witnessed a dramatic change in farming practices that disrupted this dynamic. The so-called Green Revolution used new industrial methods to grow more crops on each parcel of land with higher-yielding varieties and massive amounts of irrigation, fertilizer, and pesticides. As a result, the world’s agricultural production shifted from a long period of geographic expansion to an era of rapid industrial intensification.

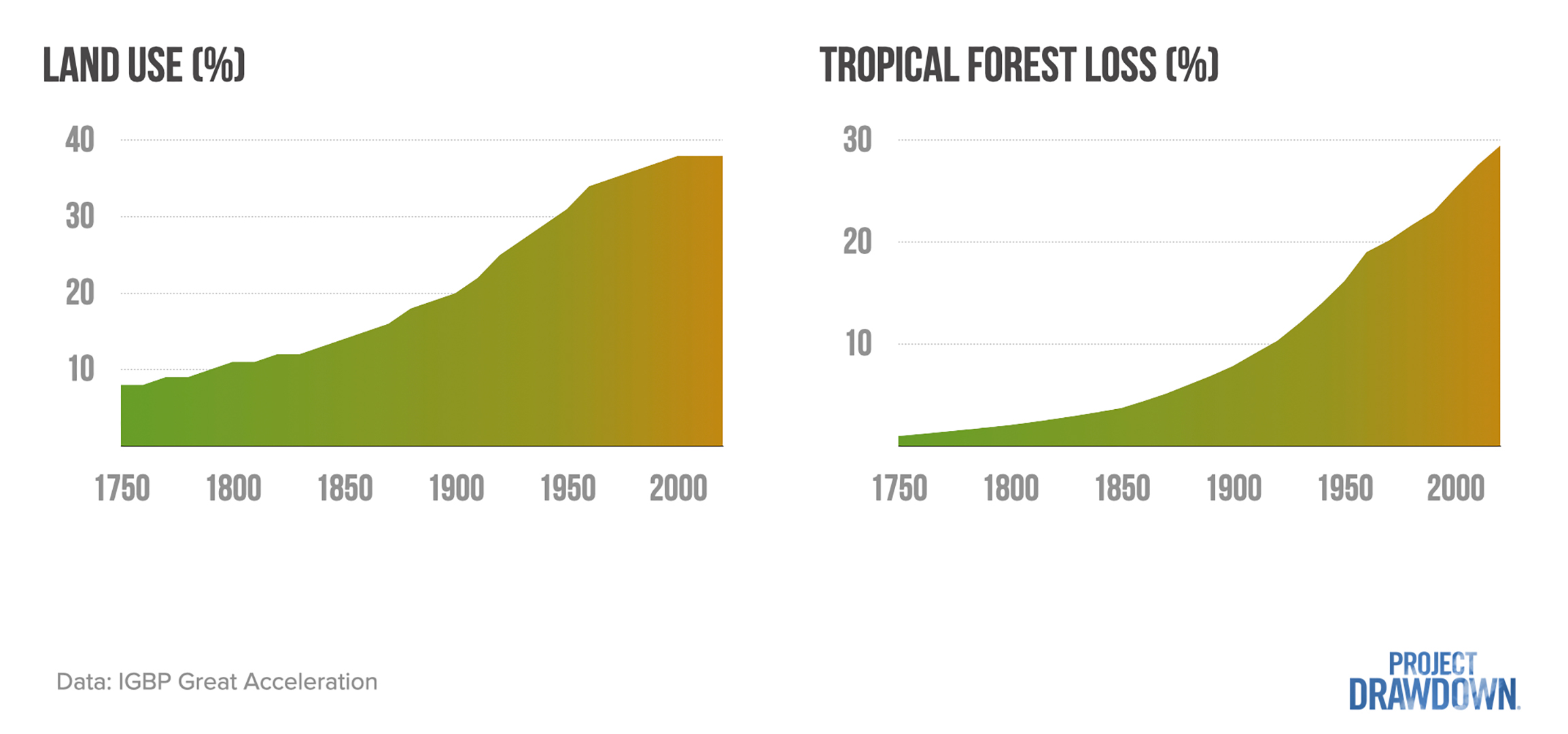

Over the last several decades, the world dramatically increased food production by continuing (albeit at slower rates) to clear land for agriculture and massively increasing the use of chemicals, irrigation, and machines. Farming – and the environment – would never be the same.