The world needs better climate pledges

Governments and businesses are looking to lead on climate change, but too many of their commitments are built on flawed “net zero” frameworks and problematic “carbon offsets.”

Authentic climate leadership requires more—a transparent and meaningful “Emissions 360” pledge that is focused on bringing real emissions to zero, helping others do the same, and equitably addressing historic climate pollution.

The world’s conversations about climate change have fundamentally shifted during the last few years. We have moved beyond old debates around whether climate change is happening (hint: it is) to more constructive discussions about addressing it.

That’s excellent news, even if we spent decades getting here.

In the sudden rush to address climate change—or at least look like we are—we have seen many companies, industry groups, and countries stake out leadership positions. Many of them have made so-called “net zero” climate pledges, complete with fancy logos and bold-sounding names.

Making and fulfilling pledges is a crucial aspect of climate leadership, but it’s only a first step. As my Project Drawdown colleague, Jamie Alexander, points out in a recent Fast Company article:

“Corporate emissions reductions pledges — however ambitious they may be for a particular company — completely miss the deeper issues that the climate crisis demands we grapple with, and only play at the edges of the revolutionary change we need.”

She calls for companies to adopt more robust climate pledges and targets, as well as push for better climate policy, support stronger climate action in the community, and be transformative climate leaders. And she’s right.

Building better pledges is the first step in transforming climate leadership

As a cornerstone of climate leadership, the weakness of today’s pledges is particularly troubling. Without clear, robust, and scientifically-sound goals, it is impossible to raise climate action to the level Earth needs.

Today it seems “net zero” pledges are all the rage. And in the lead-up to the next big climate conference—the “COP26” meeting in Glasgow—we will see even more politicians, CEOs, and celebrities make net-zero pledges.

Unfortunately, net-zero commitments—which once seemed like a good idea—have become so distorted and abused they are now largely meaningless. Sadly, the net-zero concept has been misused by bad or indifferent actors, allowing them to make bold-sounding climate pledges without really reducing emissions at all.

Misusing “net zero”

Before it was co-opted, the term “net zero” was used by climate scientists to describe scenarios when the entire atmosphere was, on balance, no longer building up greenhouse gases. Not a company or a country. The whole planet.

These scenarios describe a time in the future when the world’s greenhouse gas emissions are dramatically reduced (by 90% or more), and carbon removal projects are only used for a few remaining emissions. They did not say we should avoid cutting emissions and rely on fictional levels of carbon removal instead. But that’s exactly what many companies are trying to do.

A lot of companies have made dubious climate commitments using accounting tricks—usually relying on problematic “carbon offsets” to make the books look better than they are. And what’s worse: Of the Fortune 500 companies that have made public net-zero commitments, only ~20% have robust frameworks, and very few are reporting their progress.

Many carbon offsets are problematic

Unfortunately, net-zero pledges have become so distorted they allow for any combination of emissions cuts and carbon offsets to reach their goal. In fact, one can claim net-zero emissions by only buying carbon offsets — without actually reducing emissions at all. This is a carbon shell game, not a real commitment to climate action.

It’s quite telling that the oil and gas industry is heavily invested in the net-zero concept. They don’t plan to actually reduce the extraction and burning of fossil fuels, of course. Instead, most are buying dubious carbon offsets to cover their operational emissions (but not the emissions from burning the oil and gas they sell) while claiming to be “net zero” climate leaders. It’s complete bullshit, of course, but it makes for good PR. It looks like action, without really acting. And that’s precisely why they’re doing it.

Carbon offsets come in two flavors—either (1) paying others to reduce their emissions, who in turn give you imaginary “carbon credits” in exchange, or (2) banking on risky or non-existent carbon removal schemes to effectively “undo” your emissions sometime in the future.

The first kind of carbon offsets, where you pay someone else to reduce emissions, is a zero-sum game. In the short run, it can help pump cash into projects that may reduce emissions somewhere—assuming the offsets are genuine. But because the entire world needs to bring emissions to zero, not just a few wealthy companies, we can’t simply pay “someone else” to do it forever. At the end of the day, there’s no one left to pay.

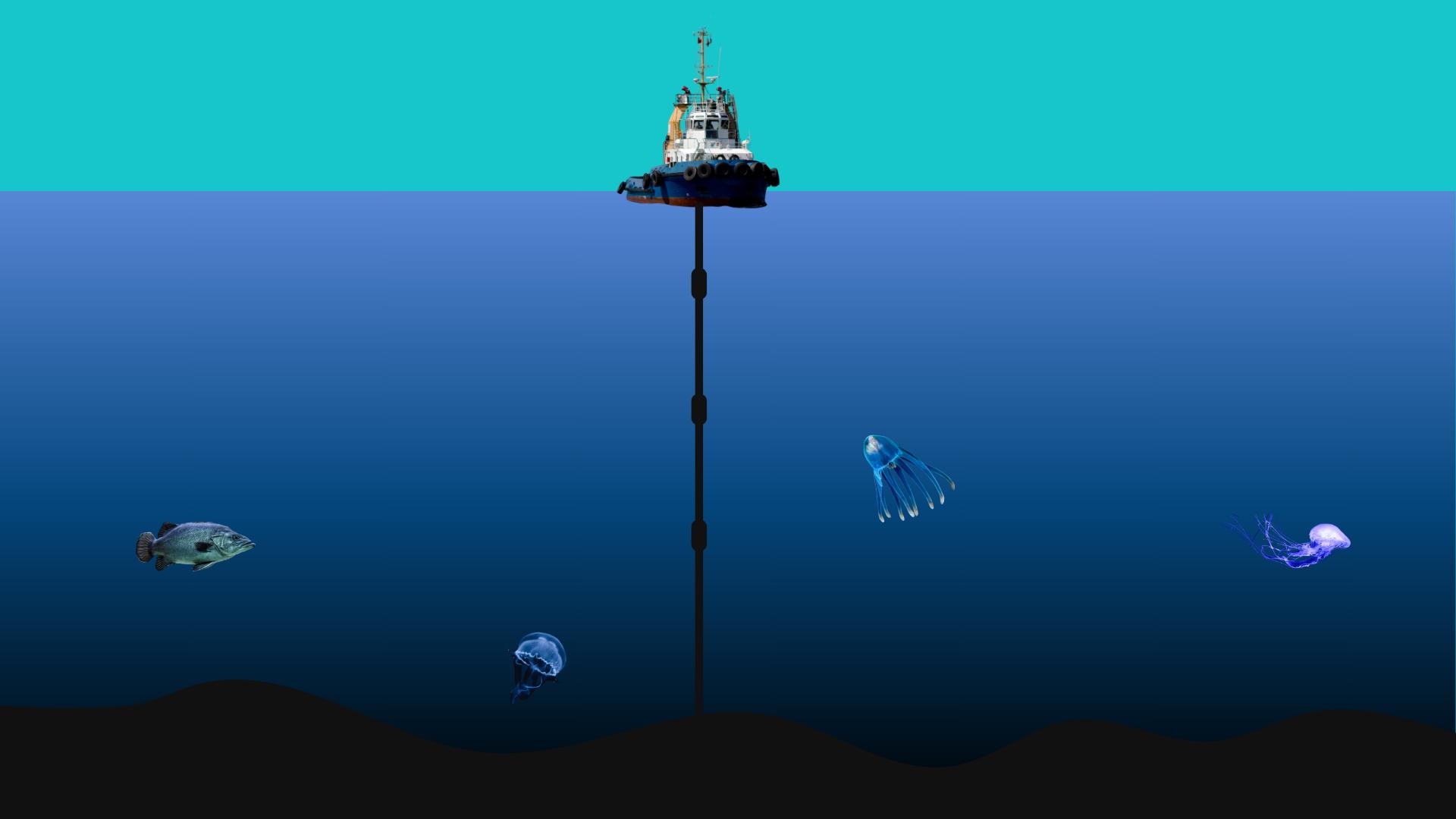

The second kind of carbon offsets, which bank on trees, farms, oceans, and machines to remove greenhouse gases from the atmosphere, makes a very risky bet. Yes, forests, soils, and coastal ecosystems can naturally absorb some carbon from the atmosphere, but only to a point. These carbon sinks are not infinite (and are probably smaller than many advocates claim), they take years to build, and they are only effective if we maintain them forever — never allowing them to be cleared, plowed, or burned down. And while carbon removal machines are getting a lot of attention, they are laughably small compared to the job at hand. Even a million-fold scale-up of carbon removal technology would only absorb a tiny percentage of our emissions.

Most of all, we need to see that vague promises of future carbon removal are just sneaky ways of allowing emissions to continue unchecked today. It’s no surprise that the biggest proponents of carbon removal technology are oil and gas companies, who have no interest in addressing climate change. It’s just a predatory delay tactic, which their industry has mastered.

Climate pledges that play games with net-zero math and rely on make-believe offsets may be good PR, as oil and gas companies have found, but they’re not addressing the real challenges we face. Serious climate commitments recognize that we need to bring emissions to zero, not “Net Zero”, as quickly as we can. We cannot achieve this with imaginary offsets, carbon trading schemes, or vague “pollute now and remove it later” promises.

Most pledges ignore the pollution we’ve already emitted

Another issue with most net-zero climate pledges is that they only look at future emissions and ignore the pollution they have already released.

A robust climate pledge needs to address historical emissions too. After all, most of the greenhouse gases we have emitted are still in the atmosphere—contributing to the continued warming of the planet. We can’t just forgive and forget them. In fact, we must ultimately find ways to remove our share of that pollution. Think “historic zero” instead of “net zero”.

If this sounds odd, it shouldn’t. After all, if a factory was dumping toxic sludge into a local lake, government agencies would order them to do two things—stop polluting the lake as quickly as possible and then clean up the pollution they already dumped there. Why is the atmosphere any different?

Most pledges only have faraway goals with no accountability

Another serious problem with many of today’s climate pledges is that they set very distant goals—like “Net Zero by 2050”—with no near-term accountability. Setting mid-century corporate goals, without any specific benchmarks in the meantime, is ridiculous. Many companies on Earth today won’t even exist in 2050. And it’s almost certain that their current CEOs and board members won’t be around. So, where’s the accountability?

A better climate pledge would start with bold, long-term goals. But they would also have more immediate metrics. For example, cutting emissions to zero by 2050 may be an excellent long-term goal, but it should come with intermediate (e.g., cutting emissions in half by 2030) and short-term (e.g., cutting emissions by at least 7% every year) milestones.

Moreover, every business should carefully audit and report their progress on climate goals along the way. The results should be reported as seriously as financial statements, with leaders taking real responsibility for them.

A new “Emissions 360” climate pledge framework

Moving forward, we need better, more transparent climate pledges. They are a necessary foundation for meaningful climate leadership. Here I outline a possible new framework—called the “Emissions 360” approach—that is built on five pillars.

(1) Cut your own emissions towards zero, not “net zero,” as quickly as possible.

Look hard at your own emissions, and find ways to reduce them as quickly as possible. Pay particular attention to cutting short-lived warming agents like methane and black carbon, which will help slow climate change even more than cutting carbon dioxide.

Some of these cuts will be easy and fast. But some emissions are going to take a while to phase out. Keep at it. Steady progress is what matters here.

Don’t even think about “offsets”, which can give the illusion of progress without truly reducing emissions.

Commit to short-term and long-term goals. Be transparent. Report how you’ve cut emissions and where you’re still struggling each year.

(2) Only use carbon removal as a last resort—for truly unavoidable emissions.

One of the most significant abuses of net-zero frameworks allows companies to make vague promises of future carbon removal to avoid cutting emissions today. This kind of carbon shell game is designed to delay climate action and can no longer be tolerated.

However, there may be a few areas where cutting greenhouse gas emissions will be exceptionally difficult or physically impractical.

These truly unavoidable emissions cases might justify some limited carbon removal projects. Carbon neutral (or negative) ways to make jet fuel, cement, and steel come to mind. But that’s about it. Carbon removal should only be used to offset emissions as a last resort, decades from now, after every practical means of cutting them has been exhausted.

Promises of future carbon removal can no longer be used as a dodge, avoiding the real work of cutting emissions today. In particular, carbon removal schemes should never be used to justify the continued use of fossil fuels, bad agricultural practices, or wasteful materials.

(3) Pay the “Social Cost of Carbon” for your ongoing pollution.

As your company works to cut emissions, donate significant sums of money (based on the “Social Cost of Carbon” for your ongoing pollution) to help advance the world’s broader climate efforts. Ideally, these funds would help others (especially disenfranchised and vulnerable communities) reduce their emissions, become more climate resilient, and address long-standing climate justice issues.

But, once again, don’t count these donations as “offsets” to your own emissions. They’re not, and they never were. Just do it because it’s the right thing to do. Or count it as a business cost. Either way, I suspect you will be rewarded for a more transparent, honest, and forthright way of addressing your emissions—and for supporting others around the world to address climate change.

(4) Don’t stop here: Address your historic emissions too.

Strong climate pledges should also commit to removing as much of your historic climate pollution from the atmosphere as possible. In other words, try to reach “historic zero” emissions, reflecting the impact your company has had over time. This will help reduce future climate change and address the long-standing inequities in greenhouse gas emissions seen around the world.

Lay out a plan to address these historic emissions with transparent, carefully-managed carbon removal projects. It may be impossible to sequester all of your historical emissions, of course—given the physical and technological limits of carbon removal—but we should do as much as we can.

This is one place where well-managed carbon removal projects make sense. Using carbon removal to avoid reducing our ongoing emissions is a mistake, and perpetuates a false image of meaningful climate action. Instead, let’s use this technology (and its limited removal capacity) to address historical emissions, not future ones.

(5) Carefully weigh issues of climate justice in everything you do.

Climate change presents a lens through which we can see some of the worst injustices of human history. The rich and powerful have benefitted most from the rise of the fossil-fueled economy, while other, disenfranchised communities — especially people of color and those in poorer countries — paid the highest price. And today’s generations still enjoy the spoils of a fossil-powered, high-energy world and a stable planetary environment. But unless we change our ways quickly, future generations might not see either one.

Addressing climate change requires more than restoring the balance of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. This is necessary, but not sufficient. Along the way, we must be careful that climate solutions do not introduce more even more inequities, injustices, and harm to people alive today—particularly the most vulnerable among us—or generations yet to come.

This piece was originally published on Dr. Jonathan Foley's Medium page June 16, 2021. Foley is a climate and environmental scientist, writer, and speaker. He is also the executive director of Project Drawdown, the world’s leading resource for climate solutions.