References

Alvarez, R., Zavala-Araiza, D., Lyon, D. R., Allen, D. T., Barkley, Z. B., Brandt, A. R., Davis, K. J., Herndon, S. C., Jacob, D. J., Karion, A., Kort, E. A., Lamb, B. K., Lauvaux, T., Maasakkers, J. D., Marchese, A. J., Omara, M., Pacala, S. W., Peischl, J., Robinson, A. L., Shepson, P. B., Sweeney, C., Townsend-Small, A., Wofsy, S. C., & Hamburg, S. P. (2018). Assessment of methane emissions from the U.S. oil and gas supply chain. Science, 361(6398), 186-188. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aar7204

Anejionu, O. C., Whyatt, J. D., Blackburn, G. A., & Price, C. S. (2015). Contributions of gas flaring to a global air pollution hotspot: spatial and temporal variations, impacts and alleviation. Atmospheric Environment, 118, 184-193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2015.08.006

Beck, C., Rashidbeigi, S., Roelofsen, O., & Speelman, E. (2020). The future is now: how oil and gas companies can decarbonize. McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/oil-and-gas/our-insights/the-future-is-now-how-oil-and-gas-companies-can-decarbonize

Carbon Limits. (2014). Quantifying cost-effectiveness of systematic leak detection and repair program using infrared cameras. https://www.catf.us/resource/quantifying-cost-effectiveness-ldar/

Clean Air Task Force. (2022). Fossil fumes (2022 update): A public health analysis of toxic air pollution from the oil and gas industry. https://www.catf.us/resource/fossil-fumes-public-health-analysis/

Climate & Clean Air Coalition. (2021). Global methane assessment: Summary for decision makers. https://www.ccacoalition.org/resources/global-methane-assessment-summary-decision-makers

Climate & Clean Air Coalition. (n.d.). Methane. Retrieved July 19, 2024. https://www.ccacoalition.org/short-lived-climate-pollutants/methane#:~:text=While%20methane%20does%20not%20cause,rise%20in%20tropospheric%20ozone%20levels.

Climateworks Foundation. (2024). Reducing methane emissions on a global scale. https://climateworks.org/blog/reducing-methane-emissions-on-a-global-scale/

Conrad, B. M., Tyner, D. R., Li, H. Z., Xie, D. & Johnson, M. R. (2023). A measurement-based upstream oil and gas methane inventory for Alberta, Canada reveals higher emissions and different sources than official estimates. Earth & Environment. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-01081-0

DeFabrizio, S., Glazener, W., Hart, C., Henderson, K., Kar, J., Katz, J., Pratt, M. P., Rogers, M., Ulanov, A., & Tryggestad, C. (2021). Curbing methane emissions: How five industries can counter a major climate threat. McKinsey Sustainability. https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/business%20functions/sustainability/our%20insights/curbing%20methane%20emissions%20how%20five%20industries%20can%20counter%20a%20major%20climate%20threat/curbing-methane-emissions-how-five-industries-can-counter-a-major-climate-threat-v4.pdf

Dunsky. (2023, July 21). Canada’s methane abatement opportunity. https://dunsky.com/project/methane-abatement-opportunities-in-the-oil-gas-extraction-sector/

Fawole, O. G., Cai, X. M., & MacKenzie, A. R. (2016). Gas flaring and resultant air pollution: A review focusing on black carbon. Environmental pollution, 216, 182-197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2016.05.075

Fiore, A. M., Jacob, D. J., & Field, B. D. (2002). Linking ozone pollution and climate change: The case for controlling methane. Geophysical Research Letters, 29(19), 182-197. https://doi.org/10.1029/2002GL015601

Giwa, S. O., Nwaokocha, C. N., Kuye, S. I., & Adama, K. O. (2019). Gas flaring attendant impacts of criteria and particulate pollutants: A case of Niger Delta region of Nigeria. Journal of King Saud University-Engineering Sciences, 31(3), 209-217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksues.2017.04.003

Global Energy Monitor (2024). Global Methane Emitters Tracker [Data set, September 2024 release]. Retrieved April 18, 2025 from https://globalenergymonitor.org/projects/global-methane-emitters-tracker/

Global Methane Initiative (2019). GMI methane data EPA [Data set]. https://www.globalmethane.org/methane-emissions-data.aspx

Global Methane Initiative (2024). 2023 Accomplishments in methane mitigation, recovery, and use through U.S.-supported international efforts. https://www.epa.gov/gmi/us-government-global-methane-initiative-accomplishments

Global Methane Pledge. (n.d.). Global methane pledge. Retrieved August 16, 2024 from https://www.globalmethanepledge.org/

Guarin, J. R., Jägermeyr, J., Ainsworth, E. A., Oliveira, F. A., Asseng, S., Boote, K., ... & Sharps, K. (2024). Modeling the effects of tropospheric ozone on the growth and yield of global staple crops with DSSAT v4. 8.0. Geoscientific Model Development, 17(7), 2547-2567. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-17-2547-2024

Hong, C., Mueller, N. D., Burney, J. A., Zhang, Y., AghaKouchak, A., Moore, F. C., Qin, Y., Tong, D., & Davis, S. J. (2020). Impacts of ozone and climate change on yields of perennial crops in California. Nature Food, 1(3), 166-172. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-020-0043-8

ICF International. (2016). Economic analysis of methane emission reduction potential from natural gas systems. https://onefuture.us/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/ONE-Future-MAC-Final-6-1.pdf

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). (2023). In: Climate change 2023: Synthesis report. Contribution of working groups I, II and III to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change [core writing team, H. Lee and J. Romero (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, pp. 1-34, doi: 10.59327/IPCC/AR6-9789291691647.001 https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/

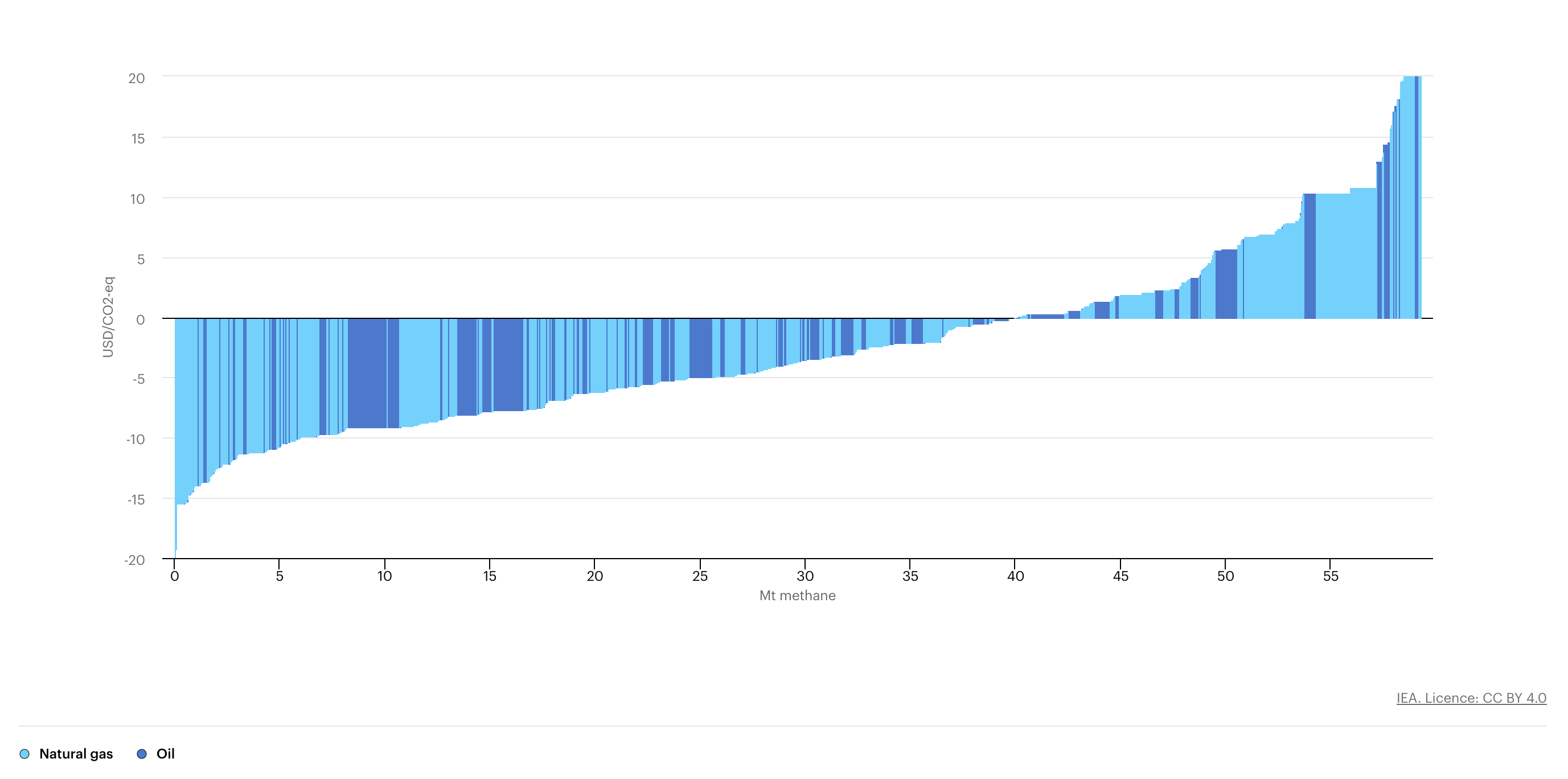

International Energy Agency. (2021). Global methane tracker 2021: Methane abatement and regulation. https://www.iea.org/reports/methane-tracker-2021/methane-abatement-and-regulation

International Energy Agency. (2023a). Financing reductions in oil and gas methane emissions. https://www.iea.org/reports/financing-reductions-in-oil-and-gas-methane-emissions

International Energy Agency. (2023b). Net zero roadmap: A global pathway to keep the 1.5℃ goal in reach - 2023 update. https://www.iea.org/reports/net-zero-roadmap-a-global-pathway-to-keep-the-15-0c-goal-in-reach

International Energy Agency. (2023c). The imperative of cutting methane from fossil fuels. https://www.iea.org/reports/the-imperative-of-cutting-methane-from-fossil-fuels

International Energy Agency. (2023d). World energy outlook 2023. https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2023

International Energy Agency. (2025). Methane tracker: Data tools. https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-tools/methane-tracker

Ismail, O. S., & Umukoro, G. E. (2012). Global impact of gas flaring. Energy and Power Engineering, 4(4), 290-302. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/epe.2012.44039

Johnson, M. R., & Coderre, A. R. (2012). Opportunities for CO₂

equivalent emissions reductions via flare and vent mitigation: A case study for Alberta, Canada. International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control, 8, 121-131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2012.02.004

Laan, T., Do, N., Haig, S., Urazova, I., Posada, E., & Wang, H. (2024). Public financial support for renewable power generation and integration in the G20 countries. International Institute for Sustainable Development. https://www.iisd.org/system/files/2024-09/renewable-energy-support-g20.pdf

Malley, C. S., Borgford-Parnell, N. Haeussling, S., Howard, L. C., Lefèvre E. N., & Kuylenstierna J. C. I. (2023). A roadmap to achieve the global methane pledge. Environmental Research: Climate, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.1088/2752-5295/acb4b4

Mar, K. A., Unger, C., Walderdorff, L., & Butler, T. (2022). Beyond CO₂

equivalence: The impacts of methane on climate, ecosystems, and health. Environmental Science & Policy, 134, 127-136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2022.03.027

Marks, L. (2022). The abatement cost of methane emissions from natural gas production. Journal of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists, 9(2). https://doi.org/10.1086/716700

Methane Guiding Principles Partnership. (n.d.). Reducing methane emissions on a global scale. Retrieved August 16, 2024 from https://methaneguidingprinciples.org/

MethaneSAT. (2024). Solving a crucial climate challenge. Retrieved September 2, 2024 https://www.methanesat.org/satellite/

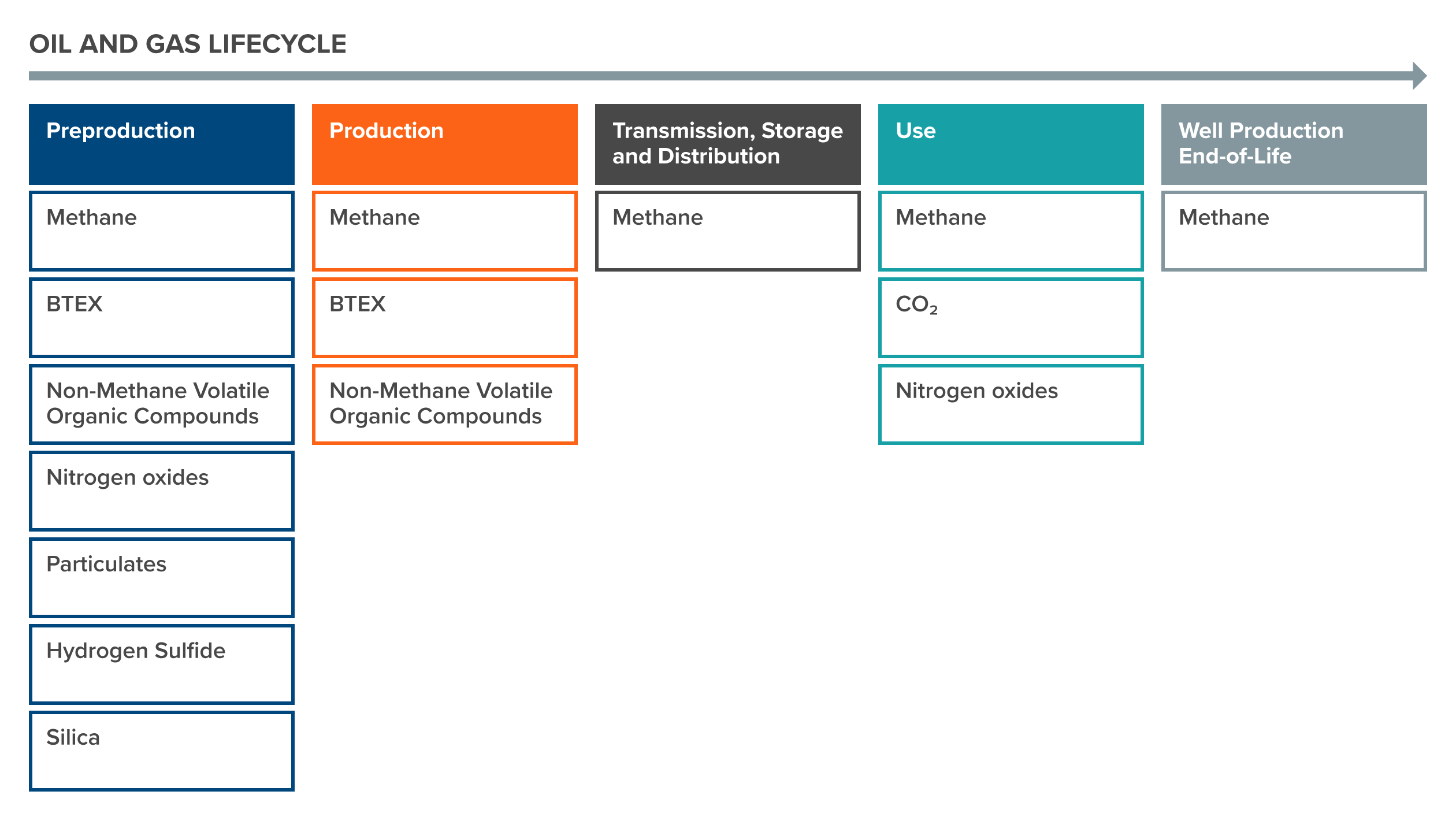

Michanowicz, D. R., Lebel, E. D., Domen, J. K., Hill, L. A. L., Jaeger, J. M., Schiff, J. E., Krieger, E. M., Banan, Z., Goldman, J. S. W., Nordgaard, C. L., & Shonkoff, S. B.C. (2021). Methane and health-damaging air pollutants from the oil and gas sector: Bridging 10 years of scientific understanding. PSE Healthy Energy. https://www.psehealthyenergy.org/work/methane-and-health-damaging-air-pollutants-from-oil-and-gas/

Mills, G., Sharps, K., Simpson, D., Pleijel, H., Frei, M., Burkey, K., Emberson, L., Cuddling, J., Broberg, M., Feng, Z., Kobayashi, K. & Agrawal, M. (2018). Closing the global ozone yield gap: Quantification and cobenefits for multistress tolerance. Global Change Biology, 24(10), 4869-4893. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14381

Moore, C. W., Zielinska, B., Pétron, G., & Jackson, R. B. (2014). Air impacts of increased natural gas acquisition, processing, and use: A critical review. Environmental Science & Technology, 48(15), 8349–8359. https://doi.org/10.1021/es4053472

Motte, J., Alvarenga, R. A., Thybaut, J. W., & Dewulf, J. (2021). Quantification of the global and regional impacts of gas flaring on human health via spatial differentiation. Environmental Pollution, 291, 118213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2021.118213

National Atmospheric and Ocean Agency (2024). Carbon cycle greenhouse gases in CH₄

. Retrieved July 19, 2024. https://gml.noaa.gov/ccgg/trends_ch4/

Ocko, I. B., Sun, T., Shindell, D., Oppenheimer, M. Hristov, A. N., Pacala, S. W., Mauzerall, D. L., Xu, Y. & Hamburg, S. P. (2021). Acting rapidly to deploy readily available methane mitigation measures by sector can immediately slow global warming. Environmental Research, 16(5). https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/abf9c8

Odjugo, P. A. O. & Osemwenkhae, E. J. (2009). Natural gas flaring affects microclimate and reduces maize (Zea mays) yield.. International Journal of Agriculture and Biology, 11(4), 408-412. https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/full/10.5555/20093194660

Oil and Gas Climate Initiative. (2023). Building towards net zero. https://www.ogci.com/progress-report/building-towards-net-zero

Olczak, M., Piebalgs, A., & Balcombe, P. (2023). A global review of methane policies reveals that only 13% of emissions are covered with unclear effectiveness. One Earth, 6(5), 519–535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2023.04.009

Pembina Institute. (2024). Comments on environment and climate change Canada’s (ECCC) regulations amending the regulations respecting reduction in the release of methane and certain volatile organic compounds (upstream oil and gas sector). https://www.pembina.org/reports/2024-02-joint-methane-submission-eccc.pdf

Project Drawdown. (2021). Climate solutions at work. https://drawdown.org/publications/climate-solutions-at-work

Project Drawdown. (2022). Legal job function action guide. https://drawdown.org/programs/drawdown-labs/job-function-action-guides/legal

Project Drawdown. (2023). Government relations and public policy job function action guide. https://drawdown.org/programs/drawdown-labs/job-function-action-guides/government-relations-and-public-policy

Project Drawdown. (2024, May 29). Unsung (climate) hero: The business case for curbing methane | presented by Stephan Nicoleau [video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y5y0i-RMfJ0

Ramya, A., Dhevagi, P., Poornima, R., Avudainayagam, S., Watanabe, M., & Agathokleous, E. (2023). Effect of ozone stress on crop productivity: A threat to food security. Environmental Research, 236(2), 116816. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2023.116816

Ravikumar, A. P., & Brandt, A. R. (2017). Designing better methane mitigation policies: The challenge of distributed small sources in the natural gas sector. Environmental Research Letters, 12(4), 044023. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa6791

Rissman, J. (2021). Benefits of the build back better act’s methane fee. Energy Innovation. https://energyinnovation.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Benefits-of-the-Build-Back-Better-Act-Methane-Fee.pdf

Sampedro, J., Waldhoff, S., Sarofim, M., & Van Dingenen, R. (2023). Marginal damage of methane emissions: Ozone impacts on agriculture. Environmental and Resource Economics, 84(4), 1095-1126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-022-00750-6

Schiffner, D., Kecinski, M., & Mohapatra, S. (2021). An updated look at petroleum well leaks, ineffective policies and the social cost of methane in Canada’s largest oil-producing province. Climatic Change, 164(3-4). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-021-03044-w

Shindell, D., Sadavarte, P., Aben, I., Bredariol, T. O., Dreyfus, G., Höglund-Isaksson, L., Poulter, B., Saunois, M., Schmidt, G. A., Szopa, S., Rentz, K., Parsons, L., Qu, Z., Faluvegi, G., & Maasakkers, J. D. (2024). The methane imperative. Frontiers. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/science/articles/10.3389/fsci.2024.1349770/full

Schmeisser, L., Tecza, A., Huffman, M., Bylsma, S., Delang, M., Stanger, J., Conway, TJ, and Gordon, D. (2024). Fossil Fuel Operations Sector: Oil and Gas Production and Transport Emissions [Data set]. RMI, Climate TRACE Emissions Inventory. Retrieved April 18, 2025 from https://climatetrace.org

Smith, C., Nicholls, Z. R. J., Armour, K., Collins, W., Forster, P., Meinshausen, M., Palmer, M. D., & Watanabe, M. (2021). The earth’s energy budget, climate feedbacks, and climate sensitivity supplementary material (climate change 2021: The physical science basis. Contribution of working group I to the sixth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). https://www.ipcc.ch/

Tai, A. P., Sadiq, M., Pang, J. Y., Yung, D. H., & Feng, Z. (2021). Impacts of surface ozone pollution on global crop yields: Comparing different ozone exposure metrics and incorporating co-effects of CO₂.

Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 5, 534616. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2021.534616

Tradewater. (2023). Methane. Retrieved August 16, 2024, from https://www.ogci.com/progress-report/building-towards-net-zero

Tran, H., Polka, E., Buonocore, J. J., Roy, A., Trask, B., Hull, H., & Arunachalam, S. (2024). Air quality and health impacts of onshore oil and gas flaring and venting activities estimated using refined satellite‐based emissions. GeoHealth, 8(3), e2023GH000938. https://doi.org/10.1029/2023GH000938

UN Environment Program. (2021). Global methane assessment: Benefits and costs of mitigating methane emissions. https://www.unep.org/resources/report/global-methane-assessment-benefits-and-costs-mitigating-methane-emissions

UN Environment Program. (2024). An eye on methane: Invisible but not unseen. https://www.unep.org/interactives/eye-on-methane-2024/

U.S. Department of Commerce, Commercial Law Development Programme. (2023). Methane abatement for oil and gas - handbook for policymakers. https://cldp.doc.gov/sites/default/files/2023-09/CLDP%20Methane%20Abatement%20Handbook.pdf

U.S. Energy Information Administration. (2024). What countries are the top producers and consumers of oil?. https://www.eia.gov/tools/faqs/faq.php?id=709&t=6

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2019). Global non-CO₂

greenhouse gas emission projections & mitigation 2015 - 2050. https://www.epa.gov/ozone-layer-protection/transitioning-low-gwp-alternatives-residential-and-commercial-air

Van Dingenen, R., Crippa, M., Maenhout, G., Guizzardi, D., & Dentener, F. (2018). Global trends of methane emissions and their impacts on ozone concentrations. Joint Research Commission (European Commission). https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/c40e6fc4-dbf9-11e8-afb3-01aa75ed71a1/language-en

Wang, J., Fallurin, J., Peltier, M., Conway, TJ, and Gordon, D. (2024). Fossil Fuel Operations Sector: Refining Emissions [Data set]. RMI, Climate TRACE Emissions Inventory. Retrieved April 18, 2025 from https://climatetrace.org

World Bank Group. (2023). What you need to know about abatement costs and decarbonization. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2023/04/20/what-you-need-to-know-about-abatement-costs-and-decarbonisation

World Bank Group. (2024). Global flaring and methane reduction partnership (GFMR). Retrieved August 16, 2024, from https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/gasflaringreduction