Many individuals, businesses, and governments are rising to this challenge, setting targets and taking real actions to reduce their own emissions. But many more have not, either taking no meaningful action or failing to follow through on public commitments. For some climate laggards, it’s a short-sighted decision to continue growing or profiting from emissions-intensive practices. For others, particularly in emerging economies, a lack of resources – usually money – prevents them from making the changes needed to reduce their emissions.

But getting to net zero is a global endeavor: effective climate action must encompass all regions and all sectors of society. If some of us can’t or won’t step up to reduce our own emissions, then the rest of us are going to need to do more than “our share.” This is the simple and unforgiving math of the greenhouse gases accumulating in our atmosphere and the shrinking window of time we have for action.

Done right, these additional climate contributions can be an invaluable opportunity. Because they go above and beyond anyone’s or any organization’s own net-zero commitments, they can be designed and targeted to have maximal climate, environmental, and societal benefits.

Here are four principles and priorities, based on science and social responsibility, that should guide these supplemental climate actions.

First, the climate action must be real, producing quantifiable and verifiable reductions in greenhouse gas emissions or increased atmospheric carbon dioxide removal. There are a number of standards, verification methods, and evaluation resources, such as the United Nations Framework of Climate Change’s Clean Development Mechanism or the Carbon Credit Quality Initiative, that can help identify credible climate actions.

Second, since we don’t have much time, we must prioritize climate actions that are available now and have an immediate impact, so-called “emergency brake” solutions. For example, we can combat deforestation, which currently produces 11% of global emissions. Or we can plug leaks and reduce excessive fertilizer use to reduce emissions of methane and nitrous oxide, which, within our net zero window for action, have more than 80 and nearly 300 times more global warming potential than carbon dioxide, respectively. In a global crisis where time is of the essence, these are real, high-impact actions that we can take much more quickly than we can scale up carbon removal technology or even replace coal or gas power plants.

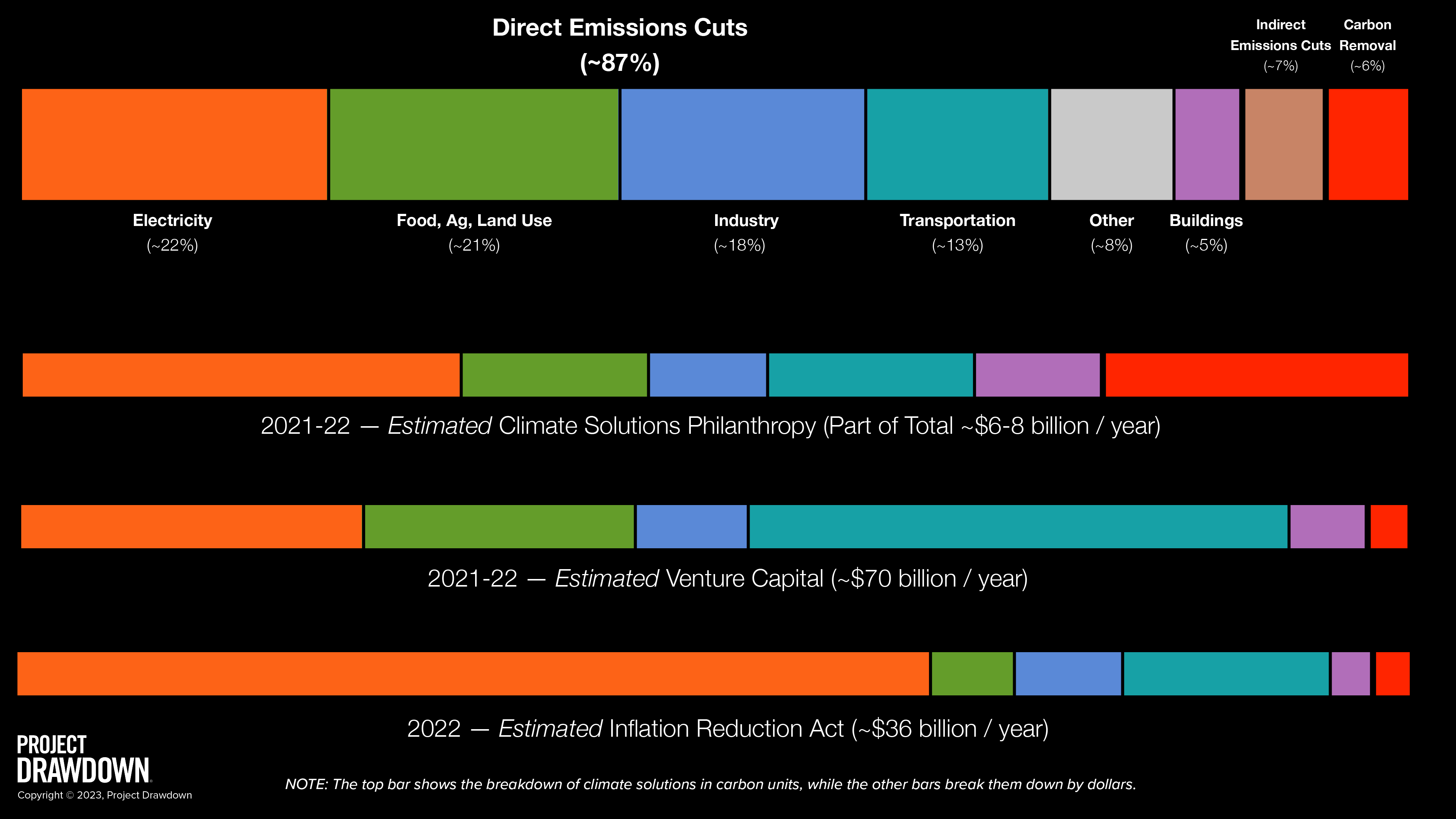

Third, focus on supporting climate actions that are underfinanced or located in regions where project developers or governments are less able to obtain funding. For example, in the United States, the electricity sector accounts for about one-quarter of total greenhouse gas emissions. Yet almost two-thirds of the money allocated by the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) is aimed at this sector. In contrast, less than 6% of IRA funding is directed toward agriculture, which is responsible for 10% of U.S. emissions. Even worse, the agriculture-related climate interventions that would have the greatest impacts, methane and nitrous oxide reductions, are largely overlooked by this program.