At the same time, the livestock industry has downplayed the role of meat and dairy production in climate change and other environmental problems. They have tried to obfuscate the sizeable climate impact of cattle’s methane emissions and have spread claims that cattle’s emissions are “natural” and mimic those of natural herbivores. However, science continually refutes and disproves these falsehoods.

Along the way, social media platforms – especially X/Twitter – have become overrun with disinformation. Some foreign governments have also jumped in, spreading false claims about beef’s impact as a way of fueling online “culture wars.” The Department of Justice recently revealed how Russia spent US$10 million to spread misinformation in the United States – including denying beef’s role in fueling climate change.

All the while, the agricultural industry has kept a solid grip on policymakers, outspending fossil fuel producers and the defense industry on lobbying. These efforts result in billions of dollars in subsidies each year (even on advertising) and favorable regulations. In the international arena, the livestock industry has been accused of pressuring the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization to downplay the importance of reducing excessive beef consumption to curb emissions. The livestock industry has even celebrated its “success” in dissuading world leaders from taking more direct action at the last international climate summit.

Without a doubt, the livestock industry is winning the PR battle. Their greenwashing and denial efforts, powerful lobbying, and media campaigns are working. Still, sensible actions can eventually win out if we face the challenges of beef overconsumption, waste, and climate change head-on and address them with sound science, evidence-based solutions, and clear-eyed, fearless speech that stands up to misinformation.

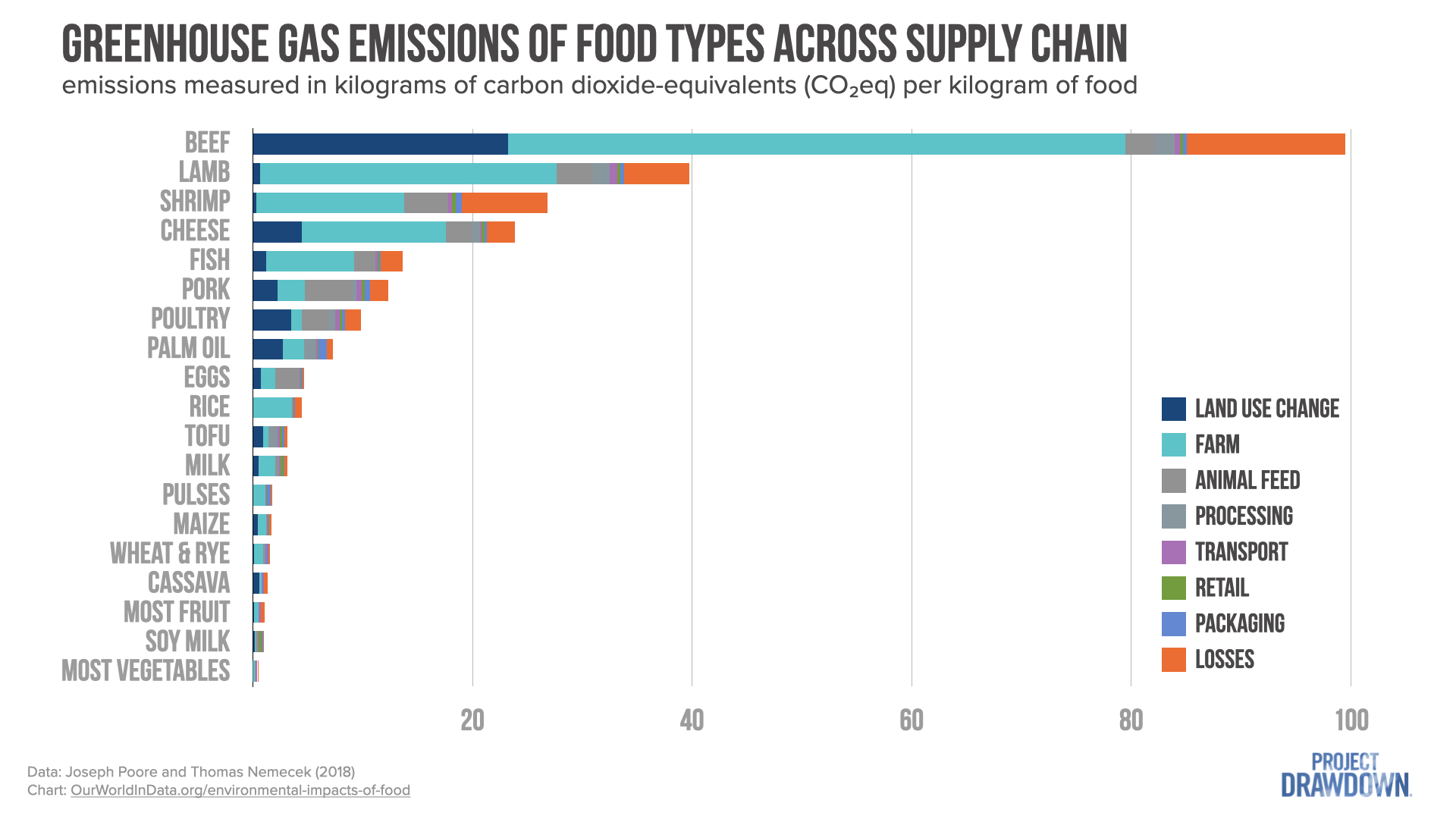

The Environmental “Beef” with Beef

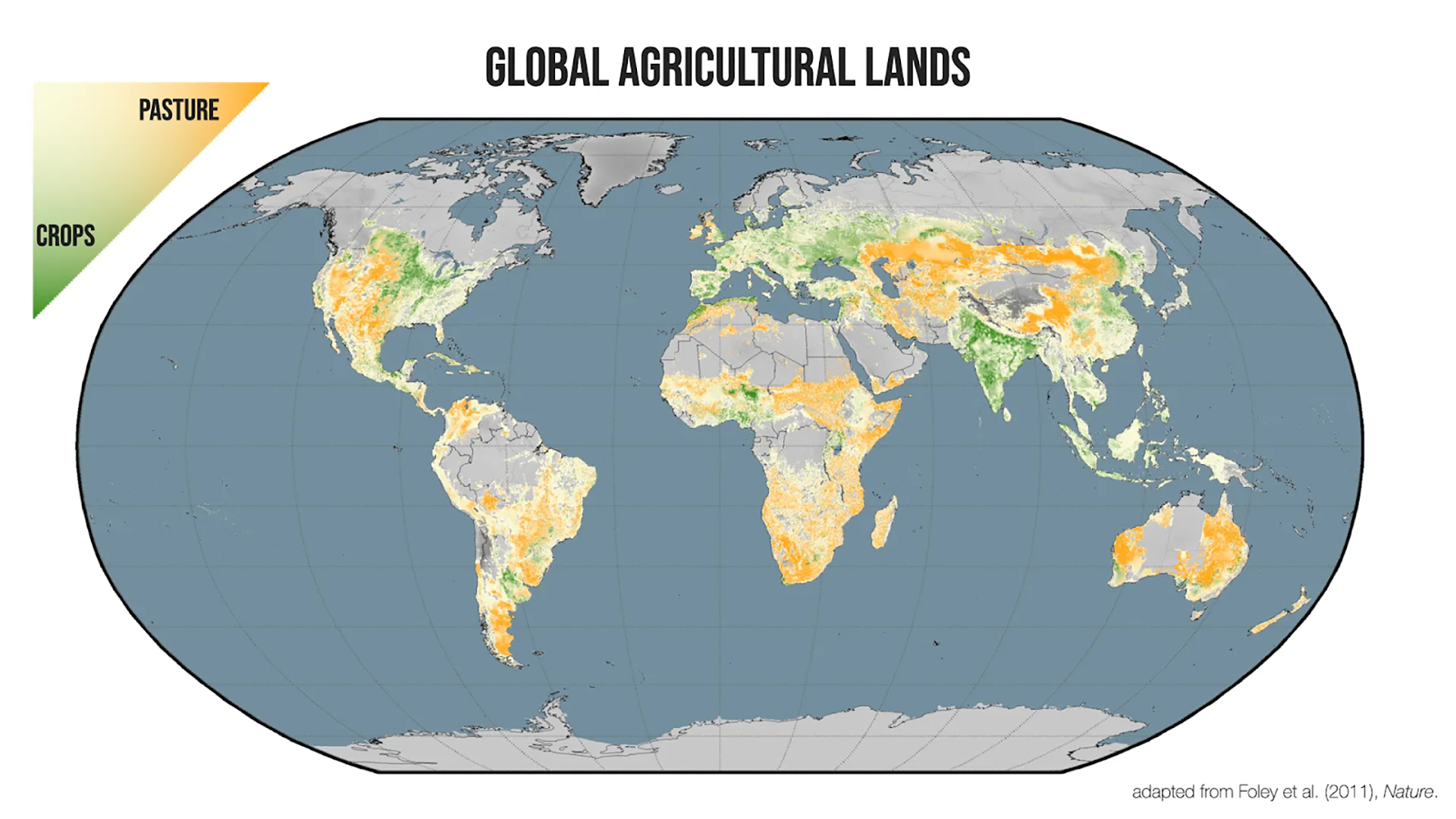

To face the environmental challenges caused by beef, we first need to understand how it is produced. That means exploring grazing and feedlot operations – and the interplay between them.

Looking at the United States, we find most cattle spend the bulk of their lives on grazing lands and are then rapidly fattened (or “finished”) for a few months in feedlots before slaughter. This combination of grazing and feedlots has been optimized to maximize beef production at the lowest cost. There are roughly 70–80 million beef cattle in the United States, with around three-quarters on grazing lands and the rest in feedlots. There are another ~20 million cattle in dairy operations. We slaughter 30–35 million cattle annually for meat, mainly from feedlots and by culling dairy herds. That amounts to one half-ton animal slaughtered each year for every ten Americans, fueling our incredible levels of beef consumption and waste.

In feedlots, cattle are kept in cramped spaces, fed grain (mainly corn) and forage (mostly alfalfa and corn silage) while pumped full of antibiotics and growth hormones. This helps bring cattle to their slaughter weight as quickly as possible and gives their meat the marbled texture that Americans have grown accustomed to.